Learning objectives

- Describe Pierre-Robin sequence

- Outline the anesthetic management considerations for patients with Pierre-Robin sequence

- Summarize the anticipated complications during the intraoperative and postoperative period among patients with Pierre-Robin sequence

- Describe the common intubation methods before administering general anesthesia among patients with Pierre-Robin sequence

Definition and mechanisms

- Pierre-Robin sequence (PRS), previously known as Pierre-Robin syndrome, is a rare congenital birth defect characterized by facial abnormalities

- The three main features are micrognathia (mandibular hypoplasia), which causes glossoptosis (posterior displacement or retractation of the tongue), which in turn causes breathing problems due to upper airway obstruction

- A wide, U-shaped cleft palate is commonly present in children with PRS

- Airway obstruction and respiratory distress are clinical hallmarks of PRS

- At birth, neonates mainly show signs of respiratory distress (i.e., stridor, retractions, and cyanosis); some manifest with feeding difficulties, gastroesophageal reflux, aspiration, and failure to thrive

- PRS is more a sequence than syndrome, because one initial malformation leads to a sequential chain of events causing the other anomalies

- PRS can occur as an isolated mandibular abnormality but is more often part of an underlying disorder or syndrome (e.g., fetal alcohol syndrome, Stickler syndrome, Treacher-Collins syndrome, and velocardiofacial syndrome)

| Associated syndrome | Associated anomalies | Anesthetic concerns |

|---|---|---|

| Fetal alcohol syndrome | Microcephaly, maxillary hypoplasia, micrognathia, short neck, ventricular septal defect, cognitive developmental delay, hyperactivity | May be difficult to ventilate and intubate Preoperative echo indicated Consider subacute bacterial endocarditis prophylaxis May be uncooperative |

| Stickler syndrome | Marfanoid appearance, airway obstruction, micrognathia, joint laxity, mitral valve prolapse | May be difficult to ventilate and intubate Care with positioning |

| Treacher-Collins syndrome | Craniofacial clefting, mandibular hypoplasia, may have obstructive sleep apnea, may have congenital heart disease | May be difficult or impossible to intubate Preoperative echo indicated Consider subacute bacterial endocarditis prophylaxis |

| Velocardiofacial (DiGeorge) syndrome | Microdeletion of chromosome 22, microcephaly, micrognathia, congenital heart disease, may have developmental delay, neonatal hypocalcemia, T-cell immune deficiency | May be difficult to intubate Preoperative echo indicated Consider subacute bacterial endocarditis prophylaxis Blood products need to be irradiated |

Signs and symptoms

- Underdeveloped mandible and small chin

- Posterior displacement or retraction of the tongue due to the small mandible

- Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and upper airway obstruction due to tongue that falls toward the throat

- High-arched palate (roof of the mouth)

- Cleft palate (opening in the roof of the mouth)

- Natal teeth (teeth that are visible at birth)

- Dysphagia (difficulty swallowing)

- Repeated upper respiratory tract and ear infections

- Temporary hearing loss due to fluid buildup behind the ear (middle ear effusion), a common symptom of cleft palate

- Speech difficulty

Causes

- Intrauterine compression of fetal mandible

- De-novo mutations on chromosomes 2 (possibly GAD1 gene), 4, 11 (possibly PVRL1 gene), or 17 (possibly SOX9 or KCNJ2 gene)

Complications

Short-term complications are due to upper airway obstruction

- Breathing difficulties, respiratory distress

- Desaturations

- Choking episodes (asphyxia)

- Difficulty feeding, malnutrition

- Aspiration risk

- Hypoxemia

Long-term complications are due to hypoxic injury and inability to feed well

- Cerebral impairment

- Pulmonary hypertension

- Cor pulmonale

- Failure to thrive

- Gastroesophageal reflux

Prognosis

- Left untreated, PRS can be fatal

- Children usually reach full development and size

- General prognosis is good once the initial breathing and feeding difficulties are overcome in infancy

Treatment

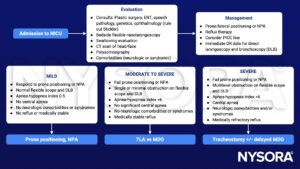

- Mild airway obstruction: Manage conservatively with nasopharyngeal airways (NPAs), prone positioning, and mechanical feeders

- Moderate or severe obstruction: Requires invasive interventions such as gastrostomy tube placement, tongue-lip adhesion (TLA), mandibular distraction osteogenesis (MDO), and tracheostomy

Anesthesia challenges

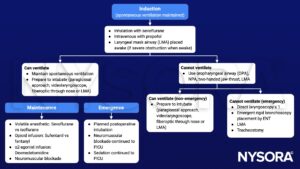

- Airway is challenging to ventilate and intubate due to craniofacial dysmorphology

- Maintaining a seal for ventilation (facemask) can be challenging due to facial deformities

- Direct laryngoscopy and tracheal intubation are difficult during infancy but become more manageable with age and (mandibular) growth

- Postoperatively, patients can spontaneously develop airway collapse

- Occur due to preexisting airway obstruction, possible OSA, chronic hypoxia, and increased opioid sensitivity

- Diagnosed with paradoxical breathing patterns, intercostal indrawing, subcostal, sternal recession, and tracheal tug

- Neonates are increasingly sensitive to opioids

- Infants who develop OSA due to glossoptosis have increased opioid sensitivity due to the upregulation of opioid receptors in the brainstem

- Patients with severe obstruction have reduced opioid requirements and require careful dose adjustments

- Feeding difficulties, swallowing disorders, and co-existing gastroesophageal reflux are frequently complicated by bronchial microaspirations and pulmonary infections → implement aspiration precautions before elective procedures

- Malnutrition and associated failure to thrive due to difficulties with feeding and airway

Management

Preoperative management

- History includes micrognathia, glossoptosis, and airway obstruction; additionally, a cleft palate may be present but this is not a required feature of PRS

- PRS can be seen as an isolated anomaly or as part of other syndromes

- Perform induction with a pediatric otolaryngology present in the OR with emergency bronchoscopy and tracheostomy equipment

Anesthetic management

Postoperative management

- Acute postoperative airway obstruction may result in hypoxia, negative pressure pulmonary edema, and death

- Patients are prone to postoperative respiratory complications (i.e., airway obstruction, oxygen desaturation, and an escalation of postoperative respiratory care) from airway obstructions due to previous airway obstruction, opioid sensitivity (associated with OSA), and surgically induced airway edema (release the mouth retractor periodically to minimize the risk of postoperative tongue edema)

- Maximize nonopioid analgesics including local anesthetic (regional blocks or local infiltration), acetaminophen, and ketorolac

- Reduce opioid doses

- Observe patients in a monitored setting with pulse oximetry

Keep in mind

- The primary concern in PRS is upper airway obstruction with subsequent respiratory distress and feeding difficulty

- Feeding difficulty may manifest as gastroesophageal reflux and failure to thrive

Suggested reading

- Hegde N, Singh A. Anesthetic Consideration In Pierre-Robin Sequence. [Updated 2022 Jul 26]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK576442/

- Cladis F, Kumar A, Grunwaldt L, Otteson T, Ford M, Losee JE. Pierre Robin Sequence: a perioperative review. Anesth Analg. 2014;119(2):400-412.

We would love to hear from you. If you should detect any errors, email us customerservice@nysora.com