Learning objectives

- Identification of patients at risk for pulmonary aspiration

- Reducing the risk of pulmonary aspiration

- Management of pulmonary aspiration

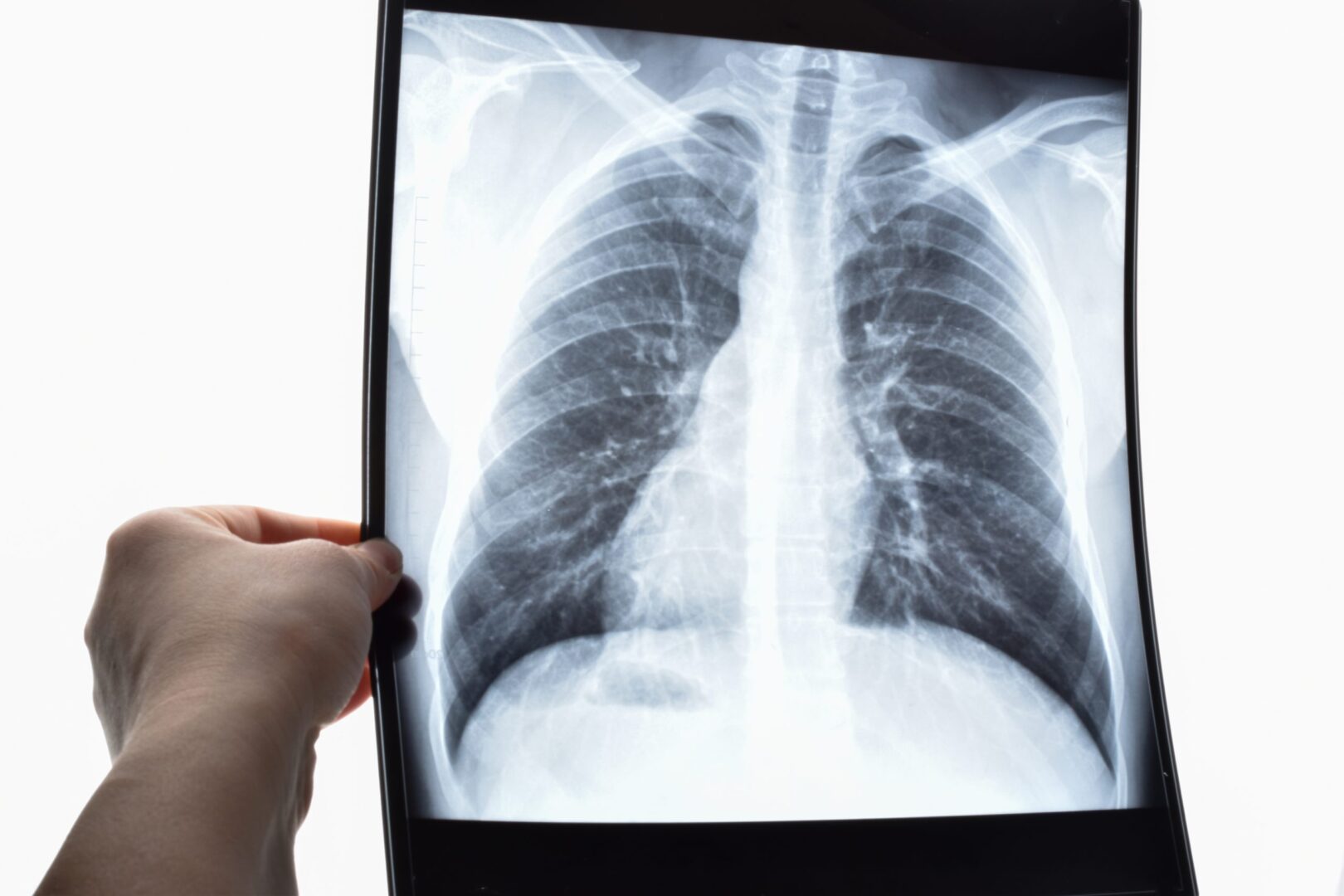

Definition

- The inhalation of oropharyngeal or gastric contents into the larynx and the respiratory tract

- Aspiration accounts for more deaths than failure to intubate or ventilate

- May lead to chemical pneumonitis, bacterial pneumonia, or acute respiratory distress syndrome

Signs and symptoms

- Symptoms can range from none to respiratory failure and subsequent cardiac arrest in a massive aspiration event

Risk Factors

| Patient factors | Full stomach |

| Emergency surgery | |

| Inadequate fasting time | |

| Gastrointestinal obstruction | |

| Delayed gastric emptying | Systemic diseases, including diabetes mellitus and Chronic kidney disease |

| Recent Trauma | |

| Opioids | |

| Increased intracranial pressure | |

| Previous gastrointestinal surgery | |

| Pregnancy (including active labor) |

|

| Incompetent lower oesophageal sphincter | Hiatus hernia |

| Recurrent regurgitation | |

| Dyspepsia | |

| Previous upper gastrointestinal surgery | |

| Pregnancy | |

| Esophageal diseases | Previous gastrointestinal surgery |

| Morbid Obesity | |

| Surgical factors | Upper gastrointestinal surgery |

| Lithotomy or head down position |

|

| Laparoscopy | |

| Cholecystectomy | |

| Anesthetic factors | Light anesthesia |

| Supra-glottic airways | |

| Positive pressure ventilation | |

| Length of surgery > 2 h | |

| Difficult airway | |

| Device factors | First-generation supra-glottic airway devices |

Prevention

| Reducing gastric volume | Preoperative fasting |

| Nasogastric aspiration | |

| Prokinetic premedication | |

| Avoidance of general anesthetics | Regional anesthesia |

| Reducing pH of gastric contents | Antacids |

| H2 histamine antagonists | |

| Proton pump inhibitors | |

| Airway protection | Tracheal intubation |

| Second-generation supraglottic airway devices | |

| Prevent regurgitation | Cricoid pressure |

| Rapid sequence induction | |

| Extubation | Awake after return of airway reflexes |

| Position (lateral, head down or upright) |

Management

- Anesthesiologists should have a low index of suspicion for aspiration

- Emergency anesthesia on its own is an important risk factor for aspiration

- Management is supportive

- The trachea should be suctioned after securing a safe airway, ideally before positive pressure ventilation to prevent the distal displacement of aspirated material

- Antibiotics should only be used if pneumonia develops, early antibiotics may lead to the selection of virulent bacteria including pseudomonas

- There is no evidence that using steroids either reduces mortality or improves outcome

Suggested reading

- Michael Robinson, MB ChB FRCA, Andrew Davidson, MA MBBS FRCA FFICM, Aspiration under anaesthesia: risk assessment and decision-making, Continuing Education in Anaesthesia Critical Care & Pain, Volume 14, Issue 4, August 2014, Pages 171–175.

- Asai T. Editorial II: Who is at increased risk of pulmonary aspiration?. Br J Anaesth. 2004;93(4):497-500.

We would love to hear from you. If you should detect any errors, email us [email protected]