Learning objectives

- Signs of placental abruption

- Degrees of placental abruption

- Management of placental abruption

Definition and mechanisms

- Hemorrhage arising from the premature separation of a normally situated placenta

- Separation of the placental bed from the decidua basalis before delivery of the fetus

- Occurs in 1% of pregnancies

- Leading cause of vaginal bleeding in the latter half of pregnancy

- Emergency with high maternal and fetal morbidity/mortality

- Major complications:

- Hemorrhagic shock

- Acute kidney injury

- Coagulopathy

- Fetal demise

- Maternal death

- Delivering premature infant

- Transfusion-associated complications

- Hysterectomy

- Recurrence has been reported in 4 to 12% of cases

Signs and symptoms

- Key diagnostic factors:

- Vaginal bleeding (although about 20% of cases have no bleeding)

- Uterine tenderness

- Rapid contractions

- Abdominal pain

- Fetal heart rate abnormalities

- The clinical implications of a placental abruption vary based on the extent of the separation and the location of the separation

- Placental abruption can be complete or partial and marginal or central

- The classification of placental abruption is based on the following clinical findings:

Class 0: asymptomatic

Class 1: mild Class 2: moderate Class 3: Severe

Discovery of a blood clot on the maternal side of a delivered placenta

Diagnosis is made retrospectively No sign of vaginal bleeding or a small amount of vaginal bleeding

Slight uterine tenderness

Maternal blood pressure and heart rate within normal limits

No signs of fetal distress No sign of vaginal bleeding to a moderate amount of vaginal bleeding

Significant uterine tenderness with tetanic contractions

Change in vital signs: maternal tachycardia, orthostatic changes in blood pressure

Evidence of fetal distress

Clotting profile alteration: hypofibrinogenemia No sign of vaginal bleeding to heavy vaginal bleeding

Tetanic uterus/board-like consistency on palpation

Maternal shock

Clotting profile alteration: hypofibrinogenemia and coagulopathy

Fetal death

- Classification of 0 or 1 is usually associated with a partial, marginal separation

- Whereas, classification of 2 or 3 is associated with complete or central separation

Stages of hypovolemic shock

I Compensated II Mild III Moderate IV Severe

Blood loss <15%; 750–1000 ml 15–30%; 1000–1500 ml 30–40%; 1500–2000 ml >40%; ≥2000 ml

Heart rate (beats/min) <100 >100 >120 >140

Arterial pressure Normal; vasoconstriction redistributes blood flow, slight increase in diastolic pressure Orthostatic changes in arterial pressure, vasoconstriction intensifies in non-critical organs (skin, muscle, gut) Markedly decreased (systolic arterial pressure <90 mm Hg); vasoconstriction decreases perfusion to abdominal organs Profoundly decreased (systolic arterial pressure <80 mm Hg); decreased perfusion to vital organs (brain, heart)

Respiration Normal Mild increase Moderate tachypnea Marked tachypnea—respiratory failure

Mental status Normal, slightly anxious Mildly anxious, agitated Confused, agitated Obtunded

Urine output (ml/h) >30 20-30 <20 None (anuria)

Capillary refill Normal (<2 s) >2 s; clammy skin Usually >3 s; cool, pale skin >3 s; cold, mottled skin

Risk factors

- Health history and past obstetrical events:

- Smoking

- Cocaine use

- Maternal age over 35 years

- Hypertension

- Placental abruption in a prior pregnancy

- Current pregnancy:

- Multiple gestation pregnancies

- Polyhydramnios

- Preeclampsia

- Sudden uterine decompression

- Short umbilical cord

- Unexpected trauma

Causes

- The exact etiology is unknown

- Specific cause is often unknown

- Trauma or injury to the abdomen

- Rarely a short umbilical cord or rapid loss of amniotic fluid

Diagnosis

- Clinical signs/symptoms

- Ultrasound (however low sensitivity)

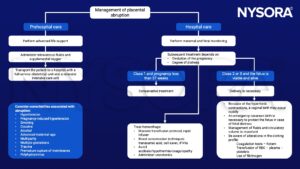

Management

Suggested reading

- Schmidt P, Skelly CL, Raines DA. Placental Abruption. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; April 1, 2022.

- Walfish, M., Neuman, A., Wlody, D., 2009. Maternal haemorrhage. British Journal of Anaesthesia 103, i47–i56.

We would love to hear from you. If you should detect any errors, email us [email protected]