Hepatorenal syndrome (HRS) stands as one of the most feared complications of advanced liver disease, representing a final common pathway of hemodynamic instability, severe portal hypertension, and progressive renal vasoconstriction. While the liver is the primary site of pathology, the syndrome’s lethal potential lies in its systemic impact, most notably, the rapid loss of kidney function in patients who are already medically fragile.

HRS occupies a critical intersection between hepatology, nephrology, intensive care, and anesthesia. It often arises in scenarios where multiple acute insults converge: an infection like spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP), gastrointestinal bleeding, over-diuresis, or even seemingly minor procedural events such as large-volume paracentesis without adequate albumin support.

For decades, the diagnosis of HRS was one of exclusion, often made late in the course of illness, when the opportunity for intervention was slim. However, recent international consensus statements from the International Club of Ascites (ICA) and the Acute Disease Quality Initiative (ADQI) are reshaping how clinicians conceptualize, detect, and treat this syndrome. The aim is to recognize kidney injury earlier, start treatment sooner, and—most importantly—bridge patients to definitive therapy: liver transplantation (LT).

Epidemiology: How common is HRS?

Accurate estimates vary because definitions have evolved, but studies suggest:

- 8–20% of hospitalized patients with cirrhosis and ascites will develop HRS-AKI.

- HRS is implicated in up to 40% of AKI cases in cirrhosis when strict criteria are applied.

- Mortality approaches 80–90% at 3 months without liver transplantation in HRS-AKI.

Risk factors include:

- Advanced cirrhosis (Child-Pugh class C)

- Persistent ascites despite diuretics

- Hyponatremia

- Recurrent SBP

- Large-volume paracentesis without albumin

- Baseline low arterial pressure and systemic vascular resistance

Historical definitions and why they’ve changed

The old paradigm

Traditionally, HRS was classified as:

- HRS-1 – Rapid progression (doubling of serum creatinine to >2.5 mg/dl in <2 weeks)

- HRS-2 – More indolent course with moderate, stable renal impairment

This schema had several limitations:

- Delayed diagnosis until advanced renal failure occurred

- Exclusion of patients with smaller rises in creatinine who might still benefit from treatment

- Over-reliance on the “48-hour albumin challenge” before labeling HRS

The new paradigm

In 2023, the ICA-ADQI joint consensus redefined HRS using KDIGO AKI criteria:

- HRS-AKI – Acute increase in creatinine or fall in urine output meeting KDIGO thresholds in a patient with cirrhosis and ascites, with no other identifiable cause

- HRS-NAKI – Subacute or chronic kidney dysfunction in cirrhosis (eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73m² >3 months)

HRS-CKD – Persistent >3 months, non-reversible renal dysfunction in cirrhosis

The albumin challenge is no longer required, though a fluid assessment remains essential to exclude hypovolemia.

Pathophysiology: a perfect storm

HRS reflects a profound imbalance between splanchnic vasodilation and renal vasoconstriction.

Key mechanisms:

- Portal hypertension → release of vasodilators (NO, CO, glucagon, prostaglandins) in the splanchnic circulation.

- Effective hypovolemia → despite total body fluid overload, arterial underfilling triggers activation of:

- Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS)

- Sympathetic nervous system

- Vasopressin release

- Renal vasoconstriction → decreased renal plasma flow, lowered GFR, reduced urine output.

- Cardiac dysfunction → “cirrhotic cardiomyopathy” limits compensatory increases in cardiac output.

- Inflammation & infection → especially SBP, amplify vasodilation and precipitate HRS.

Clinical presentation

HRS typically develops in hospitalized patients already being treated for another complication of cirrhosis.

Typical features:

- Progressive rise in serum creatinine over days to weeks

- Very low urine sodium (<10 mmol/L) without diuretic use

- Bland urine sediment (no proteinuria, hematuria)

- Often accompanied by worsening ascites and hyponatremia

Diagnosis: exclusion and precision

HRS-AKI diagnostic checklist:

- Cirrhosis with ascites

- KDIGO-defined AKI

- No shock at diagnosis

- No nephrotoxic drug exposure

- No signs of structural kidney injury:

- Proteinuria >500 mg/day

- Hematuria >50 RBC/hpf

- Abnormal renal ultrasound

Role of biomarkers:

- Urinary NGAL can help differentiate HRS from acute tubular injury (higher in ATN).

- Cystatin C may provide more accurate GFR estimates in cirrhosis.

Prevention: keeping HRS from developing

Because HRS carries such high mortality, primary prevention is crucial.

Preventive measures:

- SBP prophylaxis: norfloxacin or ciprofloxacin in high-risk patients

- Albumin in SBP: reduces the risk of renal failure and death

- Albumin after large-volume paracentesis: prevents circulatory dysfunction

- Prudent diuretic use: avoid excessive volume depletion

- Medication review: stop NSAIDs, avoid ACE inhibitors/ARBs in advanced cirrhosis

- Early treatment of infections: to prevent inflammatory vasodilation

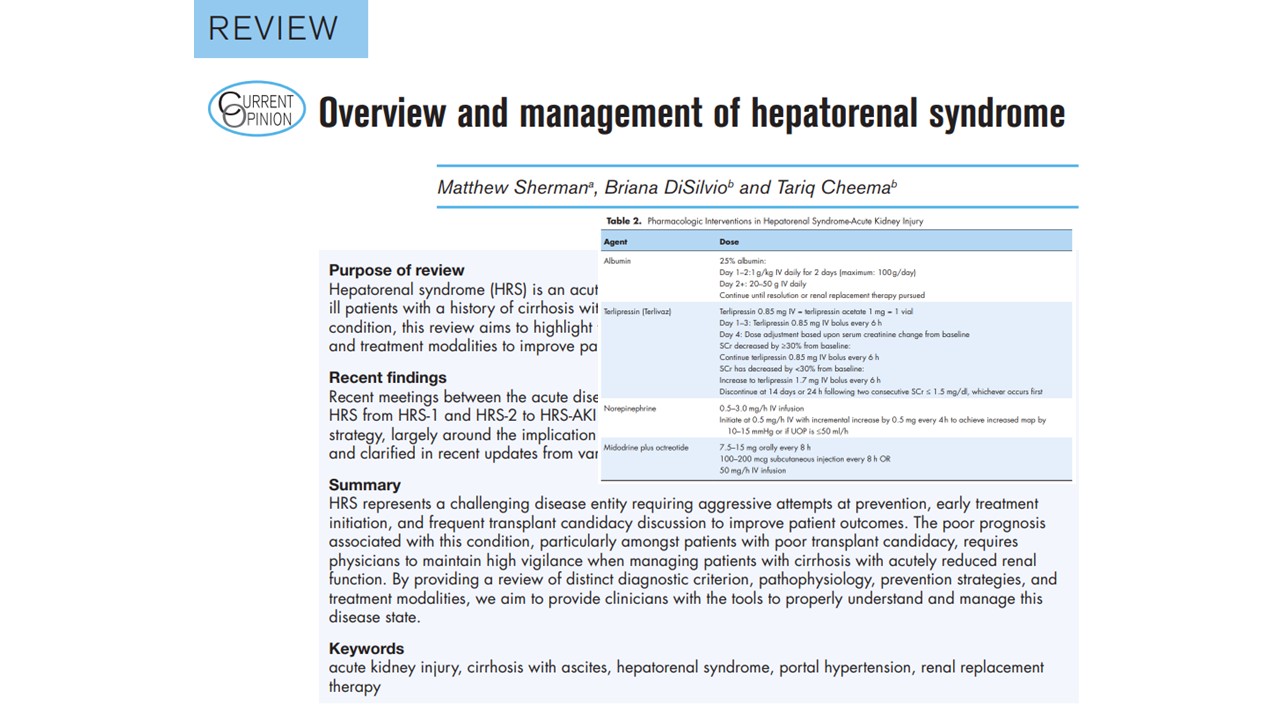

Treatment: the two-phase approach

Phase 1: Stabilization and reversal

- Albumin

- 1 g/kg/day for 2 days, then maintenance 20–50 g/day

- Improves effective arterial volume

- Vasoconstrictors

- Terlipressin (FDA-approved): 0.85–1.7 mg IV q6h; titrate up if SCr reduction <30% by day 3.

- Norepinephrine: equally effective; requires an ICU setting.

- Midodrine + Octreotide: outpatient or ward option where terlipressin is unavailable.

Phase 2: Definitive therapy

- Liver transplantation

- Only curative option

- Simultaneous liver-kidney transplant if irreversible renal injury is suspected

- Bridging strategies

- Continue vasoconstrictor + albumin

- Consider RRT for metabolic control

- Evaluate for TIPS in select patients

- Renal replacement therapy (RRT)

Limited role outside transplant, RRT should be reserved for:

- Severe electrolyte disturbance

- Acidosis

- Refractory volume overload

- Uremic symptoms

Survival without transplant is dismal (~15% at 6 months).

Prognosis

Even with treatment, the prognosis remains poor without a liver transplant.

Predictors of poor outcome:

- Higher MELD-Na

- CLIF-ACLF grade

- Need for RRT

- Sepsis

- Advanced encephalopathy

Emerging therapies and research gaps

- New vasoconstrictors with more favorable side-effect profiles

- Early detection with biomarkers

- TIPS optimization for select HRS-AKI cases

- Improved transplant allocation for patients with rapidly deteriorating renal function

Conclusion

Hepatorenal syndrome remains a life-threatening complication of advanced liver disease, with high mortality unless liver transplantation is achieved. Early recognition, rapid initiation of albumin plus vasoconstrictor therapy, and strict infection prevention are essential to improve outcomes. The recent ICA–ADQI definition changes aim to accelerate diagnosis and treatment, potentially preserving renal function. While pharmacologic measures can bridge patients to transplant, they are not curative, underscoring the need for timely referral and coordinated multidisciplinary care.

For more information, refer to the full article in Current Opinion in Anesthesiology.

Sherman M, DiSilvio B, Cheema T. Overview and management of hepatorenal syndrome. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2025 Aug 1;38(4):492-497.

Read more about hepatic and renal failure in our Anesthesiology Manual: Best Practices & Case Management.