Learning objectives

- Describe diabetic ketoacidosis

- Recognize the symptoms and signs of diabetic ketoacidosis

- Anesthetic management of a patient with diabetic ketoacidosis

Definition and mechanisms

- Diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) is a potentially life-threatening complication of diabetes mellitus

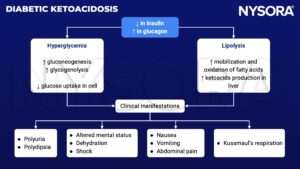

- DKA results from a relative or absolute insulin deficiency with an excess of hyperglycemic hormones (i.e., glucagon, catecholamines, cortisol, and growth hormone) leading to hyperglycemia because of increased gluconeogenesis, accelerated glycogenolysis, and impaired glucose use by peripheral tissues

- DKA leads to lipolysis and the synthesis of ketoacids to use as fuel

- Ketoacids trigger metabolic acidosis and polyuria, leading to severe dehydration

- DKA occurs most often in patients with type 1 diabetes, but can also occur in patients with type 2 diabetes (rare)

- Triggers include infection or inflammation (e.g., pneumonia, UTI, foot ulcer, abdominal [appendicitis, cholecystitis, pancreatitis]), inadequate insulin administration, myocardial infarction, stroke, certain medications (e.g., steroids, cocaine), pregnancy, and trauma

Signs and symptoms

- Polydipsia

- Polyuria

- Feeling a need to throw up and vomiting

- Abdominal pain

- Weakness and fatigue

- Deep gasping breathing (Kussmaul breathing)

- Fruity-scented breath

- Confusion

- Hyperglycemia

- Ketonuria

Risk factors

- Patients with type 1 diabetes

- Patients who often miss insulin doses

Complications

Most common complications are related to the treatment of DKA with fluids and electrolytes

- Hypoglycemia

- Hypokalemia

- Cerebral edema

Pathophysiology

Treatment

Patients with DKA receive emergency treatment in the hospital, including:

- I.v. insulin to lower ketones

- Fluids to prevent dehydration

- Electrolyte replacement: Sodium, potassium, and chloride

- Antibiotics if an infection is also present

Management

Fluids

- The average fluid deficit in DKA is 6 L

- Start with 500-1500 mL of colloid bolus if clinically hypovolemic (hypotension, tachycardia)

- Initial bolus should be normal saline (NS; 0.9% saline) bolus 10-15 mL/kg

- Change to ½ NS with 20 mEq/L potassium after that

- Replace ongoing intraoperative blood and fluid losses as usually

- Change fluid to D5W with ½ NS if blood sugar drops to 250 mg/dL and anion gap is still present → allows insulin administration to reduce ketone without causing hypoglycemia

Insulin

- Regular insulin 10 U IV bolus followed with an infusion at (blood glucose/150) U/h

- Do not stop insulin if glucose <90, rather increase i.v. glucose administration

- Consider changing to SQ insulin when the patient resumes P.O. alimentation

Electrolytes

- Follow electrolytes closely every 4-6 h (every 2 h at the very beginning) until the anion gap closed

- Potassium:

- 10-15 mEq/h for at least the first 4 h

- Irrespective of the initial potassium level, for a goal of 4–5 mEq/L

- Potassium will shift back to the intracellular compartment because of insulin and lead to hypokalemia if uncorrected

- Phosphate: 1-2 mg/dL

- Magnesium: 2 mEq/L

Acidosis

- Typically will correct itself with insulin treatment

- Administer bicarbonate only if pH <7.0 or hemodynamic instability (rare)

Triggering factors

- Diagnose and treat

Other

- Consider thromboprophylaxis depending on the risk

Prevention

- Manage diabetes

- Monitor blood sugar levels

- Adjust the insulin dose as needed

- Check the ketone level

- Be prepared to act quickly

Keep in mind

- DKA is a life-threatening medical emergency characterized by the biochemical triad of ketonemia, hyperglycemia, and acidemia

- Bedside monitoring of capillary ketones, glucose, blood gases, and electrolytes is used to make the initial diagnosis and guide management

- Balanced electrolyte solutions resolve acidosis faster, but contain insufficient potassium to justify their safe use except in critical care

- Continuation of long-acting insulins may reduce complications during the transition from i.v. to SQ insulin

- Early involvement of diabetic specialist teams is required

Suggested reading

- Levy N, Penfold NW, Dhatariya K. Perioperative management of the patient with diabetes requiring emergency surgery. BJA Education. 2017;17(4):129-136.

- Hallet A, Modi A, Levy N. Developments in the management of diabetic ketoacidosis in adults: implications for anaesthetists. BJA Education. 2016;16(1):8-14.

- Patel K, Kohli-Seth R. Chapter 210. Diabetic Ketoacidosis. In: Atchabahian A, Gupta R. eds. The Anesthesia Guide. McGraw Hill; 2013. Accessed January 17, 2023.

We would love to hear from you. If you should detect any errors, email us [email protected]