Cardiac arrest during surgery or in the intensive care unit (ICU) differs markedly from other settings. In the community or hospital wards, arrests may be unwitnessed and unexpected. In contrast, perioperative cardiac arrests are often anticipated, witnessed, and responded to more rapidly. This crucial difference forms the foundation for a new iteration of clinical guidelines — Perioperative Resuscitation and Life Support (PeRLS).

Published in Anesthesiology (2025), this updated guidance by Moitra et al. is the third iteration of PeRLS. It synthesizes current evidence into practical recommendations for anesthesiologists and critical care specialists. Developed by a panel of 17 international experts using the GRADE methodology, PeRLS focuses on timely diagnosis, targeted intervention, and context-specific algorithms for perioperative cardiac emergencies.

Cardiac arrest in the operating room: unique features

Perioperative cardiac arrest has an incidence of 2 to 13 per 10,000 anesthetics, with mortality ranging from 32% to 75% before discharge. Unlike community arrests, clinicians can often identify and treat reversible causes before full arrest occurs.

Key characteristics:

- Most events are witnessed and anticipated

- High degree of monitoring (e.g., arterial lines, ECG, EtCO₂)

- Timely access to pharmacologic and mechanical interventions

- Increased opportunity for diagnosis-specific resuscitation

Methodology behind PeRLS

The 2025 PeRLS guideline utilized the GRADE framework, examining 97 clinical questions, of which 12 were prioritized. Eight underwent consensus-based review, and four were evaluated using formal Cochrane systematic reviews. This dual-pronged methodology yielded:

- 13 recommendations

- 1 best practice statement

- Evidence levels range from very low to moderate certainty

Core recommendations in PeRLS 2025

- Use of pulse pressure variation (PPV) for fluid responsiveness

For suspected hypovolemia:

- Recommendation: Use PPV to guide fluid therapy

- Evidence: Very low certainty, but supports tailored resuscitation

- Caution: PPV should be used in ventilated patients with sinus rhythm and no open chest

- Respiratory rate during arrest

- Recommendation: Ventilate at 10–12 breaths/min

- Avoid: Hyperventilation (>16 breaths/min) — may reduce venous return and coronary perfusion

- Evidence: Low certainty, but supported by animal and human data

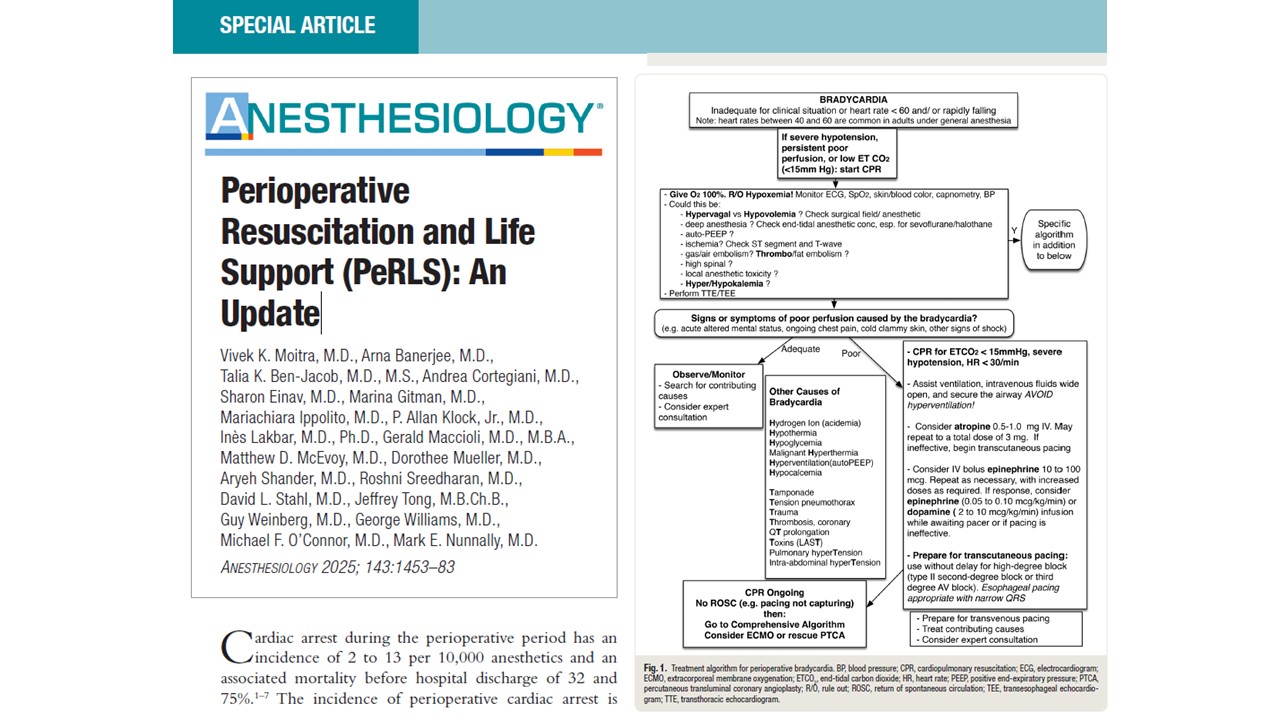

Targeted treatments for perioperative complications

- Symptomatic bradycardia

- Initial dose: 0.5 mg IV atropine

- Escalated dose: 1.0 mg IV if arrest is imminent

- Do not use: Atropine in full arrest — switch to ACLS algorithm

- Alternate options: Glycopyrrolate or pacing in selected cases

- Epinephrine: 50–100 µg IV or 200–500 µg IM as first-line

- Escalation: 100–300 µg IV if hypotension persists

- Infusion: Consider for ongoing shock (0.05–0.3 µg/kg/min)

- Other treatments: Fluids, H1/H2 blockers, corticosteroids

- Note: No recommendation for norepinephrine due to lack of evidence

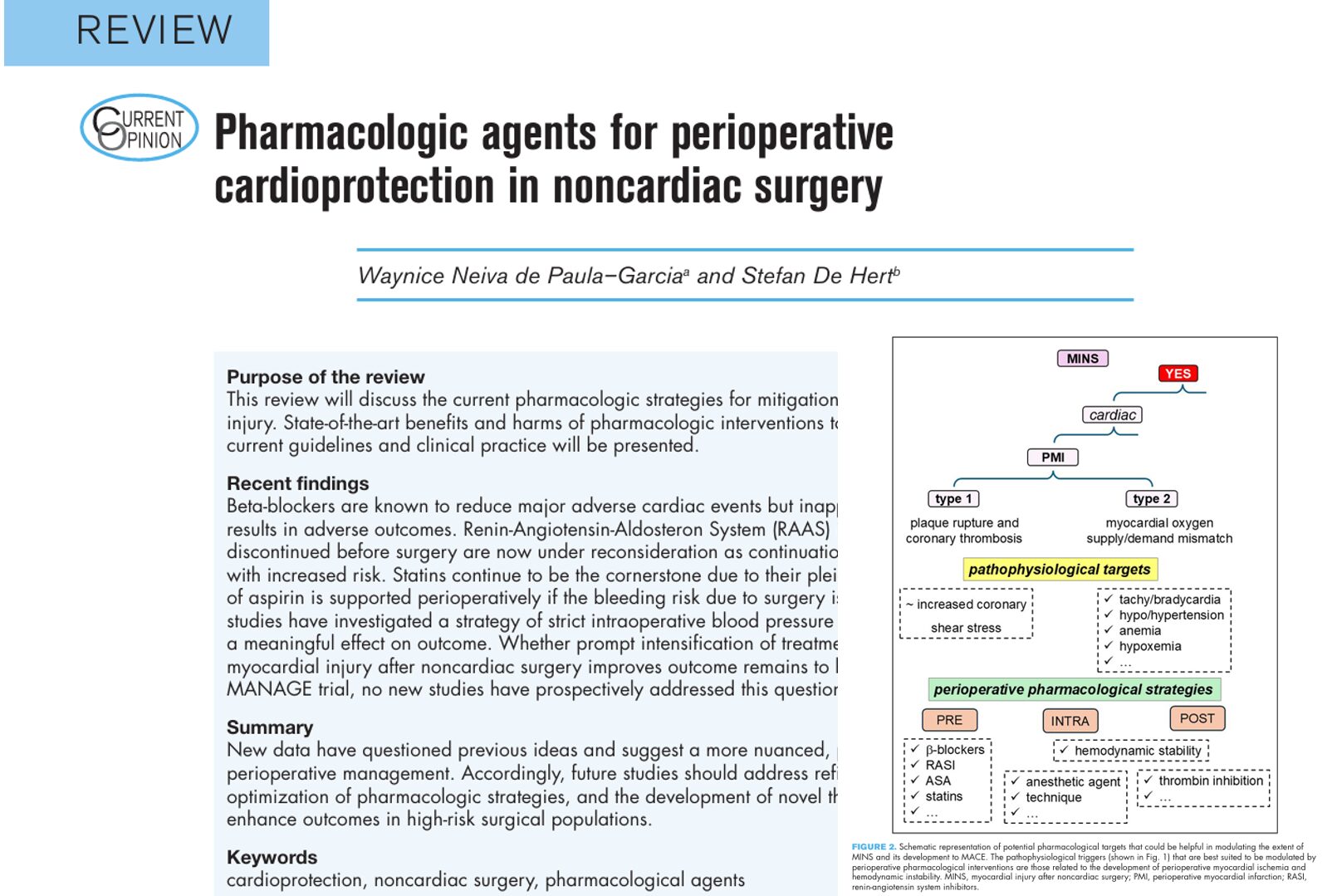

Managing complex shock scenarios

- Left ventricular shock

Characterized by:

- Low PPV

- hypotension despite fluids

Treatment options:

- Inotropes: Dobutamine, epinephrine, milrinone

- Afterload reducers: Nicardipine, hydralazine

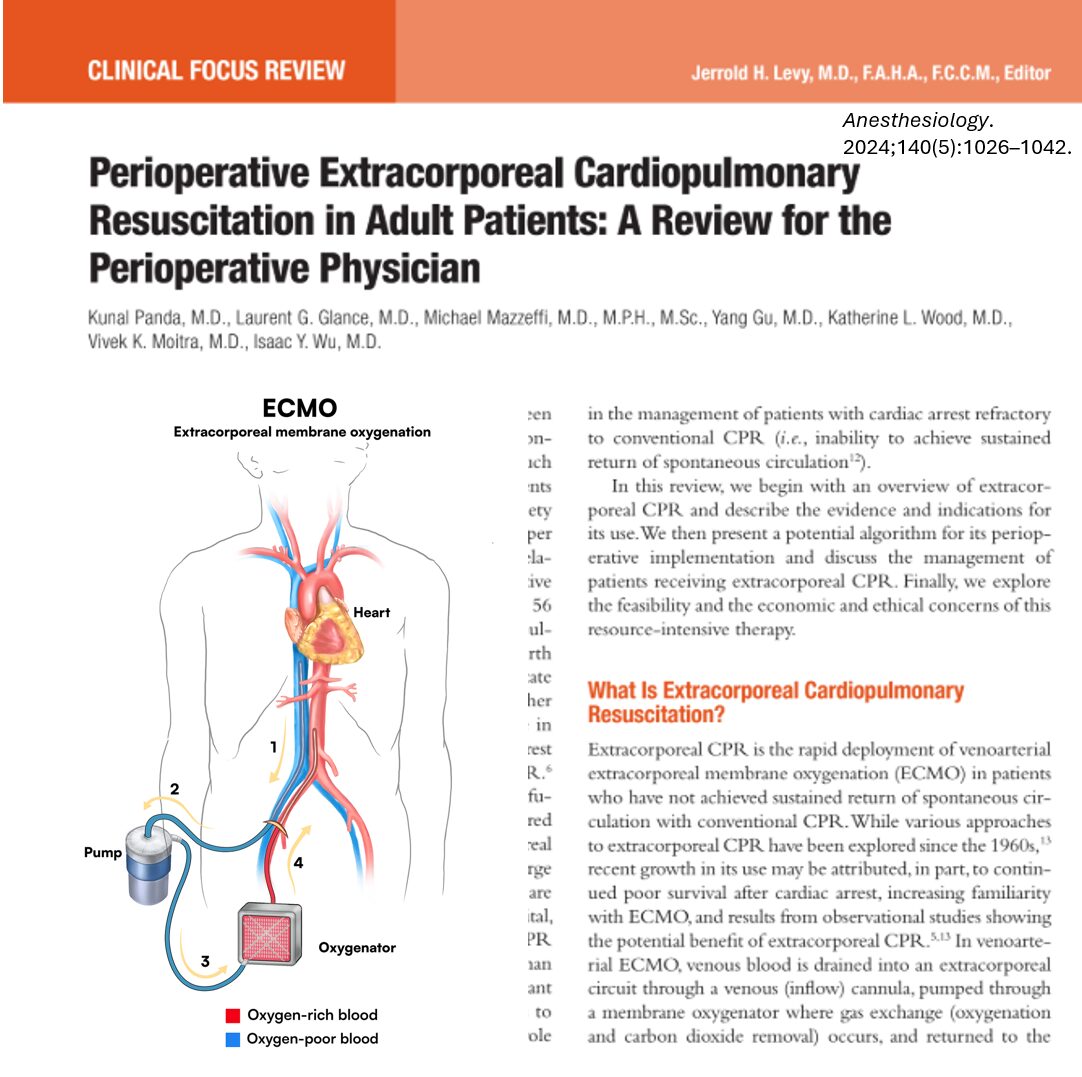

- Mechanical support: Intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP), LVAD, ECMO

- Right ventricular shock

Causes include:

- Pulmonary embolism

- Amniotic or fat embolism

- Excessive fluids

Management:

- Pulmonary vasodilators: Nitric oxide, epoprostenol

- Inotropes and vasopressors

- Mechanical support: RVAD or ECMO

- Vasopressin: Preferred in refractory cases as it spares the pulmonary vasculature

High-risk scenarios and special populations

- Triggering agents: Succinylcholine, volatile anesthetics

- Signs: Jaw rigidity, hypercapnia, hyperthermia

- Treatment: Dantrolene 2.5 mg/kg IV immediately

- Evidence: Moderate certainty from large retrospective reviews

- Secondary care: Cooling, renal protection, electrolyte correction

- Presentation: CNS signs, arrhythmias, cardiac arrest

- Treatment:

- Lipid emulsion 20%: 1.5 mL/kg bolus, then infusion

- Epinephrine: 10 µg IV for hypotension; 100–300 µg for arrest

- Avoid: Vasopressin, calcium channel blockers, lidocaine

- Evidence: Strong recommendation, low certainty due to case series and observational data

Emerging strategies: positioning and pacing

- Prone position CPR

- Recommendation: Continue CPR in the prone position if arrest occurs

- Rationale: Delaying compressions to turn the patient may worsen outcomes

- Evidence: Very low certainty but aligned with physiological rationale

- Permissive hypotension in trauma

- Target: MAP of 50 mmHg or SBP of 70 mmHg

- Goal: Minimize bleeding until definitive hemostasis

- Caution: Contraindicated in head injury or prolonged transport times

Discussion

The PeRLS 2025 update represents a paradigm shift in the approach to cardiac arrest and cardiovascular collapse in surgical and critical care settings. It champions contextualized decision-making rather than a “one-size-fits-all” ACLS protocol.

By integrating:

- Dynamic hemodynamic assessment

- Echocardiography

- Cause-specific pharmacology

- Mechanical circulatory support

- Visual algorithms for rapid action

…PeRLS elevates perioperative resuscitation to a diagnosis-driven discipline. Notably, many recommendations are conditional due to low or very low certainty of evidence, reflecting the scarcity of randomized controlled trials in critical care emergencies. Yet the strong consensus among expert panelists, physiologic rationale, and existing data provide a compelling case for their clinical use.

Conclusion

The 2025 PeRLS update is not merely an academic exercise—it is a critical tool for practice. As surgical patients become older and more complex, and as the number of high-risk procedures rises, these evidence-informed guidelines provide a clear framework for clinicians facing life-threatening complications in the perioperative setting.

Future directions should include:

- Larger multicenter registries

- High-fidelity simulation studies

- Pragmatic trials in anesthesia and critical care

Until then, PeRLS provides practical, patient-centered guidance that has the potential to improve outcomes across surgical and critical care units worldwide.

For more information, refer to the full article in Anesthesiology.

Moitra, Vivek K. M.D.1; Banerjee, Arna M.D.2; Ben-Jacob, Talia K. M.D., M.S.3; Cortegiani, Andrea M.D.4; Einav, Sharon M.D.5; Gitman, Marina M.D.6; Ippolito, Mariachiara M.D.7; Klock, P. Allan Jr M.D.8; Lakbar, Inès M.D., Ph.D.9; Maccioli, Gerald M.D., M.B.A.10; McEvoy, Matthew D. M.D.11; Mueller, Dorothee M.D.12; Shander, Aryeh M.D.13; Sreedharan, Roshni M.D.14; Stahl, David L. M.D.15; Tong, Jeffrey M.B.Ch.B.16; Weinberg, Guy M.D.17; Williams, George M.D.18; O’Connor, Michael F. M.D.19; Nunnally, Mark E. M.D.20. Perioperative Resuscitation and Life Support (PeRLS): An Update. Anesthesiology 143(6):p 1453-1483, December 2025.

Read more about Perioperative Resuscitation and Life Support in our Anesthesiology Module on NYSORA 360—an essential learning resource for residents with up-to-date, practical guidance across perioperative care.