In recent years, there has been a seismic shift in how healthcare professionals approach perioperative pain management. At the heart of this change is a growing movement toward opioid-free anesthesia (OFA) and opioid-free analgesia (OFAg)—methods designed to eliminate opioids from surgical and post-surgical care. This trend is not emerging in isolation. It reflects broader societal, clinical, and regulatory responses to the global opioid epidemic, which has left healthcare systems grappling with the dual burdens of addiction and undertreated pain.

OFA proposes an appealing vision: surgery without the risk of opioid-related side effects, dependency, or long-term misuse. But as with all paradigms that gain momentum quickly, it’s crucial to scrutinize whether OFA and OFAg deliver on their promise—or whether they risk swinging the pendulum too far in the other direction.

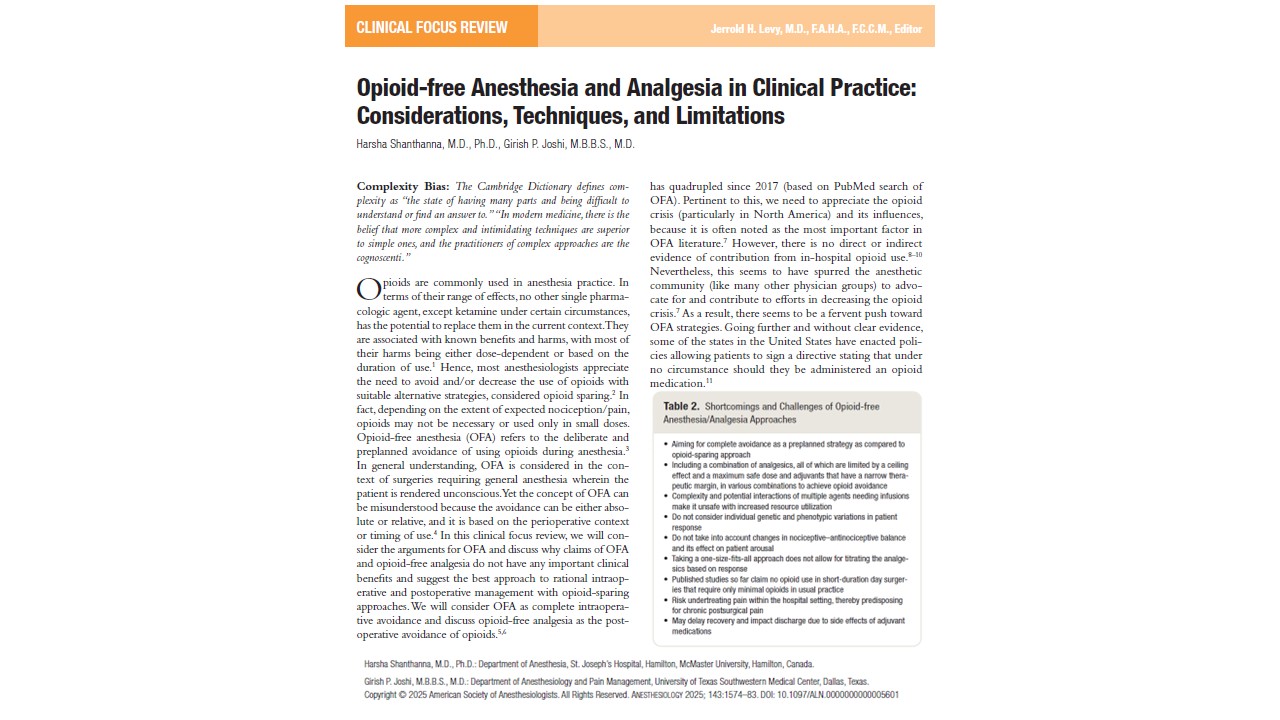

The review of Shanthanna et al. 2025 published in Anesthesiology explores the science, strategies, limitations, and realistic role of OFA in modern clinical practice. Drawing from recent evidence, it aims to help anesthesiologists, surgeons, pain specialists, and policy-makers chart a more balanced, evidence-based course for perioperative pain management.

Understanding opioid-free anesthesia and its origins

OFA refers specifically to the complete avoidance of opioids during general anesthesia, while OFAg focuses on postoperative pain control without opioids. These strategies have gained significant attention since 2017, particularly in North America, where concern over the opioid crisis has spurred clinicians and legislators to search for safer alternatives.

However, it’s critical to recognize that the opioid epidemic is largely driven by outpatient misuse, not by in-hospital use of opioids during or after surgery. Nevertheless, OFA has become a popular trend, especially in the United States, where some states allow patients to sign directives prohibiting any opioid administration—even when clinically necessary.

The role of opioids in balanced anesthesia

Modern general anesthesia aims to achieve three main goals:

- Unconsciousness

- Antinociception (pain suppression)

- Immobility

Of these, antinociception is essential, and opioids have traditionally been the most effective agents. They synergize with hypnotics to reduce the minimum alveolar concentration (MAC), which reflects anesthetic depth. Importantly, opioids are dose-titratable—allowing precision dosing in real-time, something that most non-opioid agents cannot offer.

Opioids are particularly important in blunting autonomic responses during high-stress procedures such as laryngoscopy, and they have predictable pharmacodynamics when used appropriately.

Multimodal analgesia: the foundation of opioid-sparing care

Multimodal analgesia involves using multiple nonopioid agents with different mechanisms to enhance pain control while minimizing opioid use. It is the bedrock of both OFA and modern anesthetic practice.

Common components include:

- Systemic analgesics: Acetaminophen, NSAIDs, COX-2 inhibitors

- Regional techniques: Nerve blocks, fascial plane blocks, epidurals, local infiltration

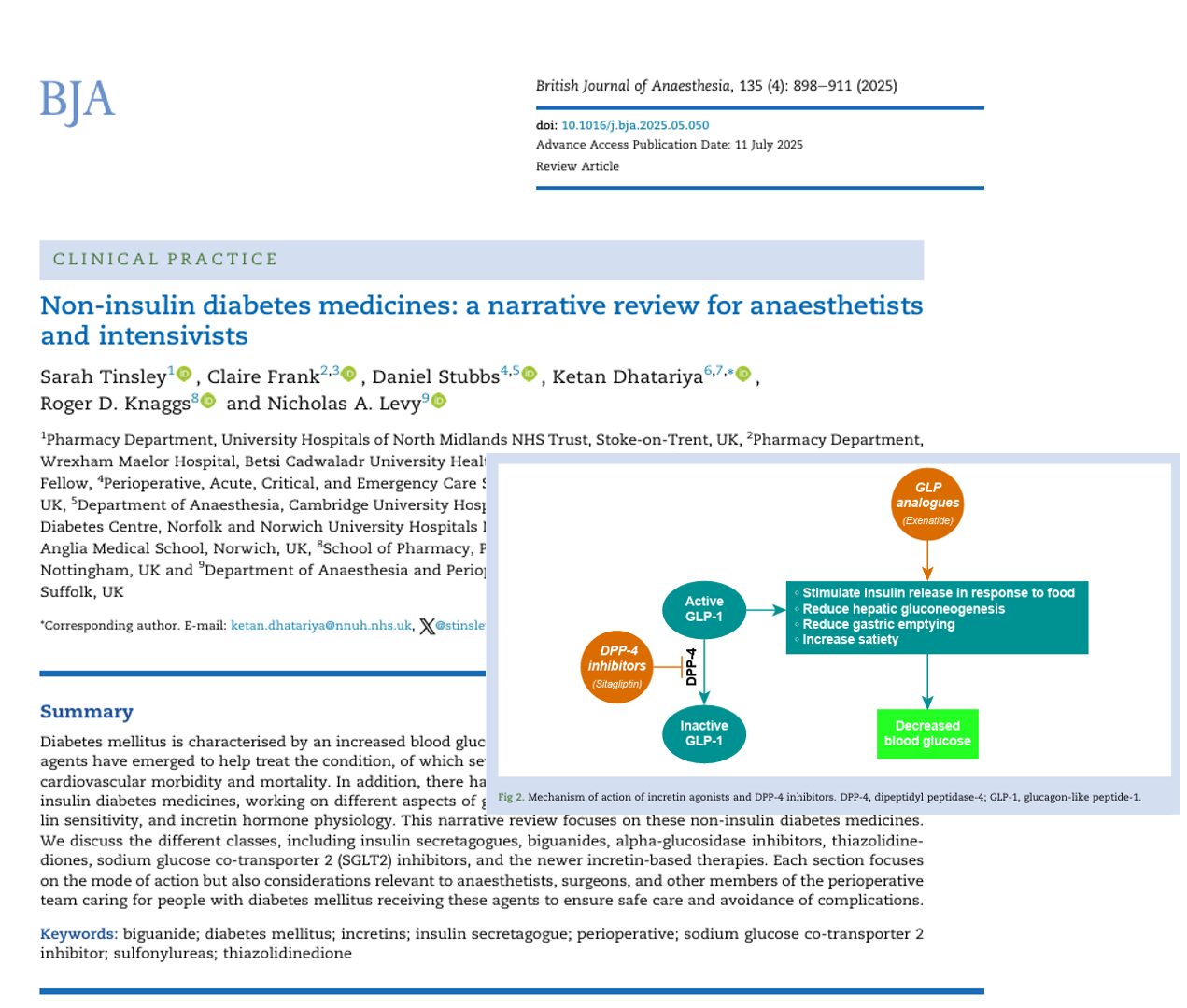

- Adjuvants:

- Dexamethasone (anti-inflammatory, reduces nausea)

- Ketamine (NMDA receptor antagonist)

- Lidocaine IV (systemic analgesia with unclear mechanism)

- Gabapentin (neuromodulator)

- Dexmedetomidine (alpha-2 agonist)

- Magnesium (calcium channel blockade)

- Esmolol (beta-blocker)

However, each component carries limitations:

- Ceiling effects cap their analgesic potential.

- Narrow therapeutic windows require careful dosing and monitoring.

- Drug interactions increase with each added agent, raising the risk of complications.

Despite its value, multimodal analgesia remains inconsistently applied across surgical disciplines and institutions.

Opioid-free anesthesia: benefits or overpromise?

Proponents of OFA cite potential benefits such as reduced opioid-related adverse events (ORADEs), improved recovery, and decreased long-term opioid use. Let’s examine the evidence behind these claims.

-

Reduction in ORADEs

ORADEs include:

- Respiratory depression

- Postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV)

- Sedation

- Ileus

- Confusion or delirium

Reality check:

- Large studies show true opioid-induced respiratory depression occurs in only 0.5% of patients.

- One major trial found higher rates of hypoxemia and ileus in the OFA group using dexmedetomidine than in those receiving remifentanil.

- The supposed benefit of reducing PONV is unsupported. Several trials showed no significant difference in PONV rates between OFA and opioid-based anesthesia.

- Gastrointestinal dysfunction (like ileus) is multifactorial, and some studies show it is worse with OFA regimens.

-

Better postoperative pain outcomes

OFA is believed to reduce pain and minimize opioid use after surgery. However:

- Meta-analyses show no consistent difference in postoperative pain or opioid use with OFA.

- High intraoperative fentanyl doses were actually associated with less chronic pain and reduced opioid prescriptions post-discharge.

- Opioid-induced hyperalgesia (OIH) is a theoretical concern but rarely causes clinical harm at typical dosages.

OFA: clinical drawbacks and risks

Despite its popularity, OFA is not without pitfalls.

Practical limitations include:

- Complexity of regimens involving multiple infusions (e.g., ketamine, lidocaine, dexmedetomidine)

- Monitoring burden due to sedative and cardiovascular side effects

- Limited analgesic ceiling of nonopioid drugs

- Risk of undertreating pain, especially in high-pain surgeries

- Delayed recovery from sedating adjuvants

- Resource intensity, requiring pumps, ICU-level monitoring, and specialized staffing

For example, gabapentin and lidocaine show minimal benefit in reducing pain, and their inclusion in OFA regimens can cause unnecessary sedation or toxicity.

Personalizing pain management: rational opioid use

Instead of blanket avoidance, experts advocate for rational, individualized opioid use.

Intraoperative strategy:

- Minimal effective opioid use, titrated to the patient and procedure.

- Use of nonopioid baseline medications: acetaminophen, NSAIDs, dexamethasone.

- Selective use of adjuvants, avoiding unnecessary polypharmacy.

- Local/regional techniques are based on the type of surgery.

- Avoid long-acting opioids unless needed during emergence from anesthesia.

Postoperative strategy:

- Continue nonopioid agents on a scheduled basis, not PRN.

- Reserve opioids as rescue therapy.

- Encourage patient mobility, breathing exercises, and functional goals.

- Educate patients on the expected pain trajectory and how to manage it safely.

Discharge planning:

- Provide a conservative opioid prescription based on actual needs.

- Use established prescribing guidelines (e.g., Michigan OPEN).

- Encourage follow-up and deprescribing plans with primary care or pain services.

The illusion of opioid-free analgesia (OFAg)

OFAg, or completely avoiding opioids after surgery, is feasible only in minor surgeries or select patients. Many studies that support OFAg focus on short procedures with inherently low analgesic needs—making their conclusions less generalizable.

Problems with OFAg:

- Fails to account for variability in pain trajectories.

- Overuses sedative infusions postoperatively.

- May lead to poor recovery and chronic pain development.

- Often ignores the fact that 30–80% of surgical patients still experience moderate to severe pain.

OFAg is sometimes less about efficacy and more about ideology. Its universal application contradicts the principles of personalized medicine.

When OFA might make sense

That said, OFA may have a role in certain cases:

- Patients with opioid intolerance or allergy

- Those with a high risk of opioid misuse or dependence

- Surgeries with minimal expected pain

- Outpatient procedures where fast recovery is prioritized

In these scenarios, OFA must be implemented carefully—with robust multimodal support and backup plans for pain escalation.

Conclusion

Opioid-free anesthesia is an innovative concept with admirable goals. But enthusiasm must be tempered by evidence. While OFA can work in select cases, the broader push to eliminate opiods from all perioperative care is premature and potentially harmful.

The path forward lies in:

- Rational, personalized opioid use

- Robust multimodal analgesia

- Evidence-based integration of regional techniques

- Realistic discharge and follow-up planning

Rather than framing opioids as inherently “bad,” clinicians should use them wisely—recognizing that for many surgeries and many patients, they remain essential to safe, humane, and effective care.

As the healthcare system continues to combat the legacy of opioid overuse, let us not forget the consequences of undertreating pain. OFA has a role—but it is a tool, not a cure-all.

For more information, refer to the full article in Anesthesiology.

Shanthanna H, Joshi GP. Opioid-free Anesthesia and Analgesia in Clinical Practice: Considerations, Techniques, and Limitations. Anesthesiology. 2025 Oct 6.

Learn more about opioid-free anesthesia in our Regional Anesthesiology Module on NYSORA 360 — an essential learning resource for residents with practical, up-to-date guidance.