Learning objectives

- Describe the importance of postoperative pain management

- Assess postoperative pain

- Manage postoperative pain

Background

- Adequate postoperative pain management is essential to enable a quick return to normal function

- Uncontrolled pain increases sympathetic activity and the stress response, leading to multisystem consequences (e.g., hyperglycemia, immunosuppression, increased risk of myocardial ischemia)

- Pain after abdominal or thoracic surgery can lead to splinting of the diaphragm and chest wall, resulting in decreased lung volumes, atelectasis, poor cough, sputum retention, infection, and hypoxia

- Pain can reduce mobility and increase the risk of thromboembolism

- Psychological effects: anxiety, feeling of helplessness

- Untreated or inadequately treated postoperative pain can lead to chronic pain

- Traditionally, opioids were the standard treatment for postoperative pain

- Today, multimodal approaches for pain management are the treatment of choice

Pain assessment

- Perform pain assessment at regular, frequent intervals and after every intervention

- The severity of pain and the effectiveness of analgesia determine the frequency

- Record pain as the fifth vital sign

- Assessment includes:

- Site, circumstances associated with onset

- Character

- Intensity (at rest and on movement)

- Associated symptoms (e.g., nausea)

- Effect on activity and sleep

- Relevant medical history

- Other factors influencing the patient’s treatment

- Current and previous medications and analgesic strategies

- Severity scales:

- Unidimensional

- Numeric (numeric rating scales, visual analog scale)

- Categorical (verbal descriptor scale)

- Multidimensional (less useful in acute postoperative pain)

- McGill Pain Questionnaire

- Leeds Assessment of Neuropathic Symptoms and Signs (LANSS) can be used to identify those at risk of developing chronic neuropathic pain

- Pictorial and behavioral scales may be needed for children or cognitively impaired patients

- FLACC scale

- Abbey pain scale

- Unidimensional

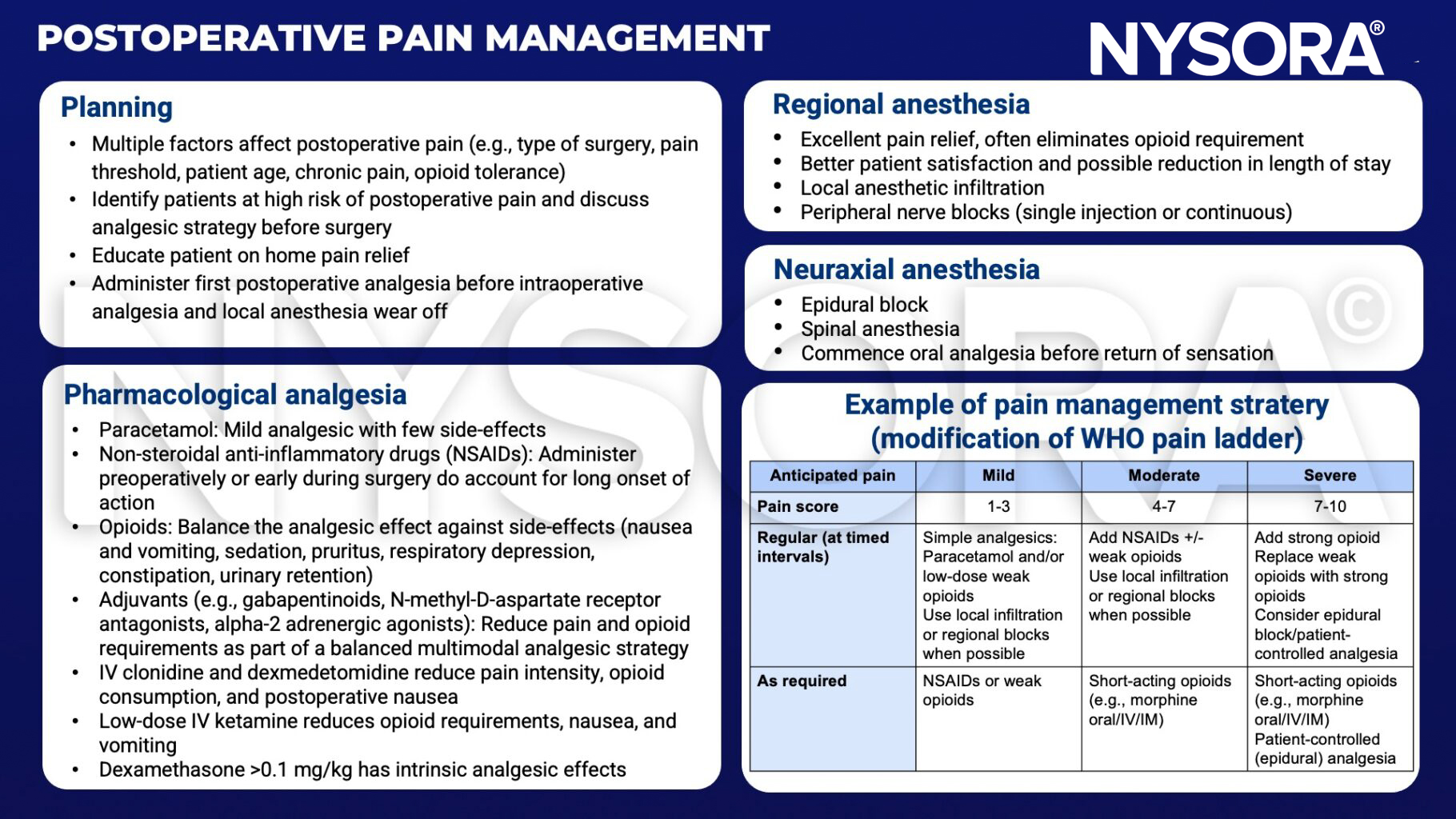

Pain management strategy

Pain in special circumstances

- Opioid-dependent patients (long-term opioids for chronic pain, opioids for cancer pain, recreational use)

- Manage patient expectations

- Provide adequate analgesia

- Prevent or manage withdrawal symptoms

- Acute neuropathic pain after surgery

- Incidence depends on type of surgery (e.g., 85% following limb amputation)

- Pre-emptive analgesia (regional techniques, ketamine, administration before start of surgery) may be helpful

- Maintain a high index of suspicion for patients at high risk

- Treatment is extrapolated from chronic neuropathic pain treatment: Tricyclic antidepressants, ketamine, anticonvulsants, lidocaine, and tramadol may have a role

Suggested reading

- Horn R, Kramer J. Postoperative Pain Control. [Updated 2022 Sep 19]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK544298/

- Pollard BJ, Kitchen, G. Handbook of Clinical Anaesthesia. Fourth Edition. CRC Press. 2018. 978-1-4987-6289-2.

- Tharakan L, Faber P. Pain management in day-case surgery. BJA Education. 2015;15(4):180-3.

Clinical updates

Lirk et al. (EJA, 2024), on behalf of the PROSPECT Working Group, provide updated procedure-specific guidelines showing that optimal analgesia after laparoscopic colorectal surgery relies on paracetamol plus NSAIDs or COX-2 inhibitors for colonic (but not rectal) surgery, combined with surgical port-site wound infiltration, with opioids reserved strictly for rescue. The review found inconsistent or minimal benefit for intravenous lidocaine, intrathecal morphine, epidural analgesia, intraperitoneal local anesthetics, and truncal blocks (TAP, QLB, ESPB), with NSAIDs specifically discouraged in rectal surgery due to concern for anastomotic leak.

- Read more about this study HERE.

Wu et al. (BJA, 2024) report that preoperative pain sensitivity is a meaningful predictor of postoperative pain, based on a systematic review and meta-analysis of 70 prospective studies including over 8,300 patients. Lower preoperative pressure and electrical pain thresholds were associated with greater acute postoperative pain, while higher temporal summation of pain was the only measure linked to both acute and chronic postoperative pain.

- Read more about this study HERE.

Hofer et al. (A&A, 2025) report that preoperative intrathecal hydromorphone (median 100 µg) in kidney transplant recipients is associated with a 66% reduction in 72-hour postoperative opioid consumption and significantly lower pain scores at 24 and 72 hours compared with no intrathecal opioid, without increased respiratory depression or length of stay. Total perioperative opioid exposure was 42% lower, with benefits most pronounced in opioid-naïve patients, though postoperative nausea and vomiting were higher (55% vs 38%). These findings support intrathecal opioids as an effective strategy to reduce systemic opioid burden and improve early analgesia in renal transplant surgery when paired with proactive antiemetic management.

- Read more about this study HERE.