Elizabeth Gartner, Elisabeth Fouché, Olivier Choquet, Admir Hadzic, and Jerry D. Vloka

INTRODUCTION

Victor Pauchet, a French surgeon, first described the sciatic nerve block in L’Anesthesie Regionale in 1920: “the site of needle insertion for blocking the sciatic nerve at the level of hip: 3 cm along the perpendicular that bisects a line drawn between the greater trochanter and the posterior superior iliac spine.” This technique has since been referred to as “The classic approach of Labat,” possibly because it was first described in the English language literature in 1923 by Gaston Labat, a student of Pauchet, in his book Regional Anesthesia: Its Technic and Clinical Application. Labat’s book went through several reprints of the first edition of one of the first English-language textbooks of regional anesthesia. Curiously, this book was very similar to L’Anesthesie Regionale. In the same year, Labat founded the American Society of Regional Anesthesia (ASRA). Anecdotally, Labat intended to name the new group “The Labat Society” in his own honor, but the name ASRA remains today as we know it. Alon Winnie eventually modified the Labat approach in 1975. Alternatives, such as the anterior approach described by George Beck in 1963 and the lithotomy approach described by Prithvi Raj in 1975, were devised to allow the sciatic nerve to be blocked in the supine patient. A number of other approaches have been proposed, most of which include minor modifications. The most useful of these newer techniques are likely the subgluteal and parasacral approach introduced by Pia di Benedetto and Philippe Cuvillon, respectively. In this chapter, we focus on the classic approach to sciatic nerve block, parasacral and subgluteal modifications, and the anterior approach.

Indications and Contraindications

Indications for sciatic nerve block include lower-limb surgery, combined with a femoral or psoas compartment block. For distal surgery of the lower extremity, however, more distal approaches such as ankle block or popliteal sciatic nerve block are preferable whenever feasible. Note that the sciatic nerve block often needs to be combined with additional blocks, such as lumbar plexus (femoral or saphenous nerve) when anesthesia of the entire lower extremity is desired.

Contraindications to sciatic nerve block may include include local infection and bed sores at the site of insertion, coagulopathy, preexisting central or peripheral nervous systems disorders, and allergy to local anesthesia.

Functional Anatomy

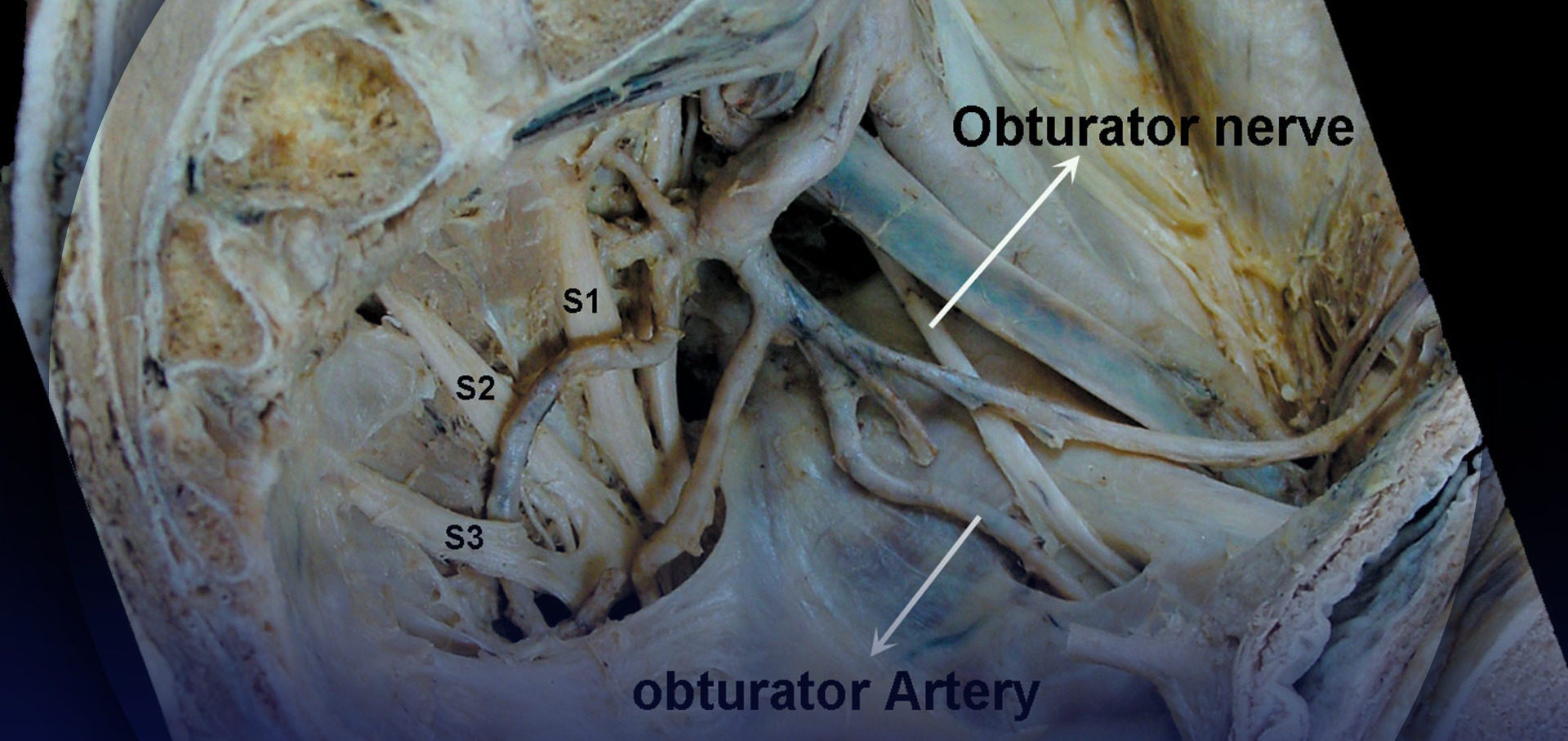

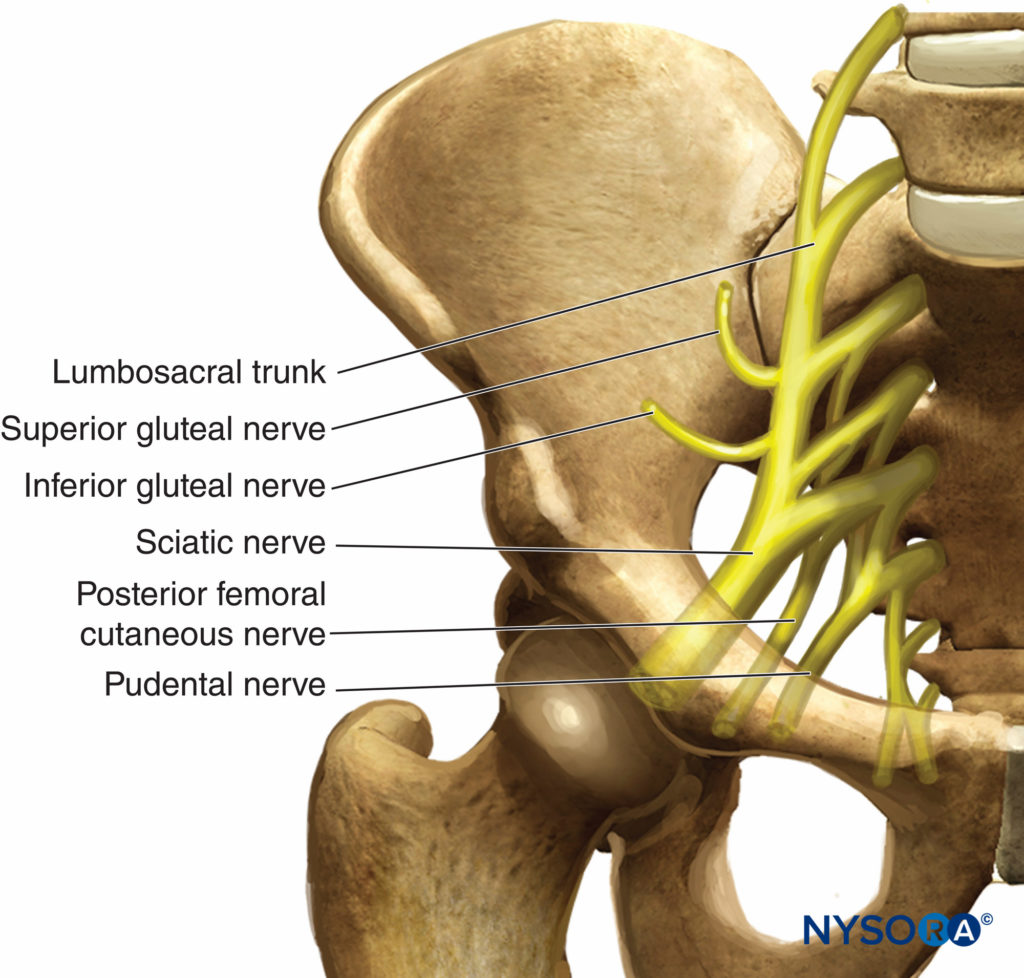

The union of the lumbosacral trunk with the first three sacral nerves forms the sacral plexus (Figure 1). The lumbosacral trunk originates from the anastomosis of the last two lum-bar nerves with the anterior branch of the first sacral nerve. This structure receives the anterior branches of the second and third sacral nerves, forming the sacral plexus. The sacral plexus is shaped like a triangle pointing toward the sciatic notch, with its base spanning across the anterior sacral foramina. It rests on the anterior aspect of the piriformis muscle and is covered by the pelvic fascia, which separates it from the hypogastric vessels and pelvic organs. Seven nerves stem from the sacral plexus: six collateral branches and one terminal branch—the sciatic nerve, the largest nerve of the plexus (Figure 2).

FIGURE 1. Formation of the sacral plexus.

FIGURE 2. Course of the sciatic nerve at the exit from the pelvis.

The sciatic nerve is the largest peripheral nerve in the body and measures more than 1 cm in width at its origin. It exits the pelvis through the greater sciatic notch below the piriformis muscle, then descends between the greater trochanter of the femur and the ischial tuberosity. The nerve then runs along the posterior thigh to the lower third of the femur, where it diverges into two large branches, the tibial and common peroneal nerves. This division may occur at any level proximal to the lower third of the femur. The common peroneal and tibial nerves are separated from their onset at the sacral plexus (15%); in this case, the common peroneal nerve typically pierces the piriformis muscle. The course of the sciatic nerve can be estimated by drawing a line on the back of the thigh beginning from the apex of the popliteal fossa to the midpoint of the line joining the ischial tuberosity to the apex of the greater trochanter. From its onset, the sciatic nerve also gives off numerous articular (hip, knee) and muscular branches.

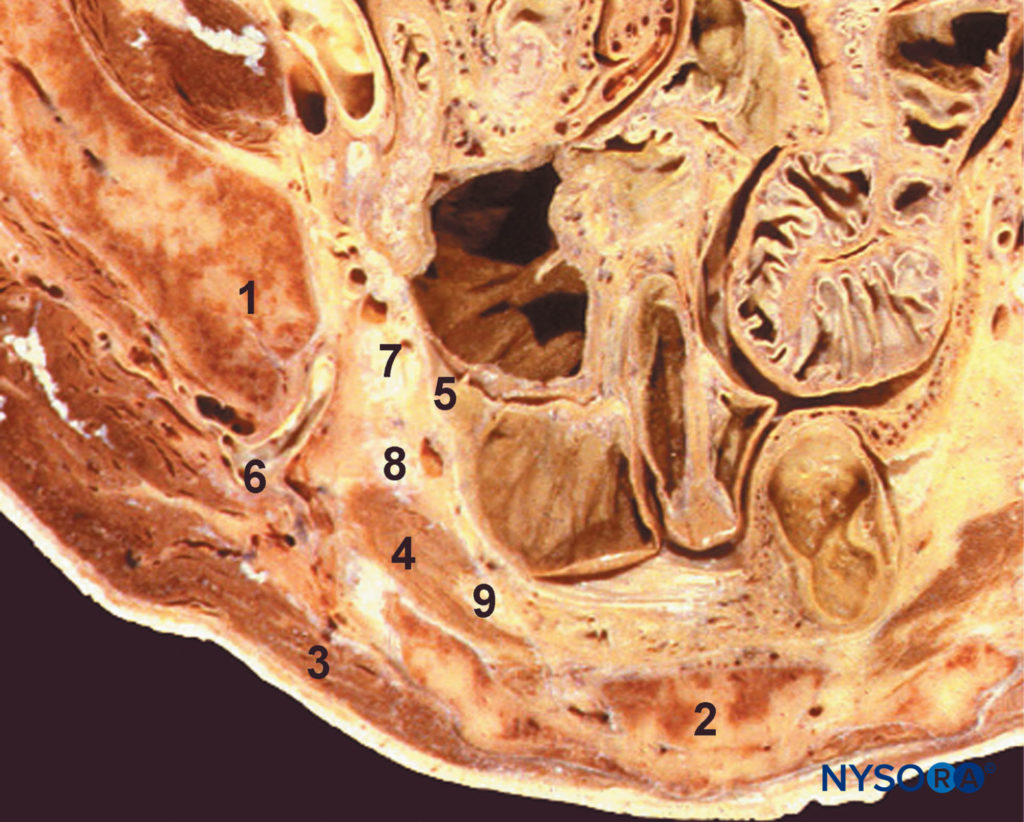

FIGURE 3. Parasacral area. Transversal section at the S3 level. 1, Iliac bone; 2, sacrum; 3, gluteal muscle; 4, piriformis muscle; 5, pelvic aponeurosis; 6, inferior gluteal plexus; 7, lumbosacral trunk; 8, first sacral root; 9, second sacral root

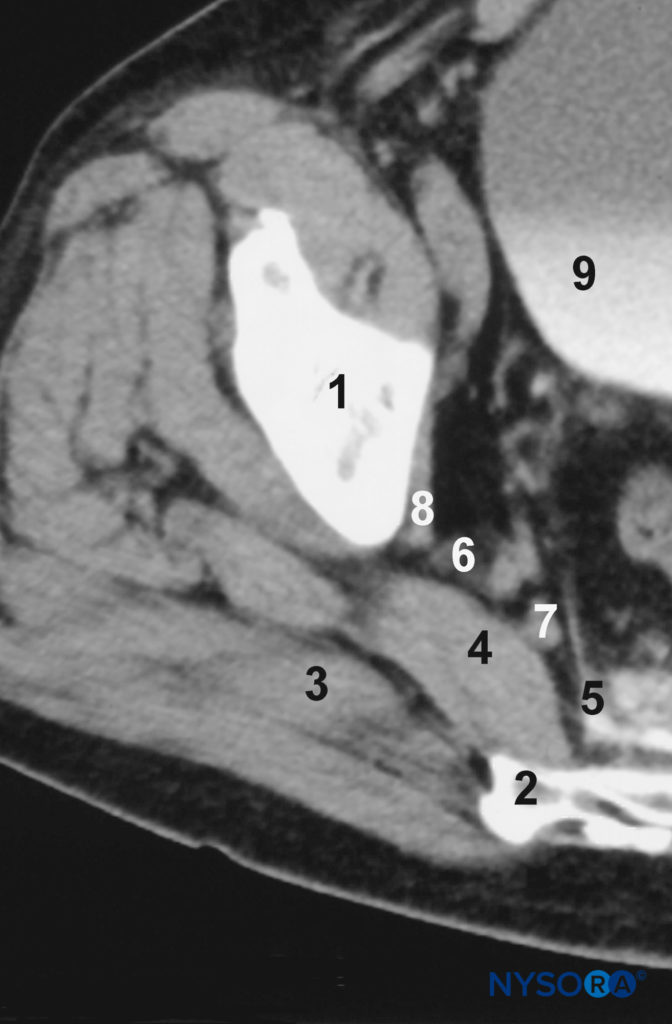

FIGURE 4. Computed tomographic (CT) scan of the parasacral area, at the S3 level. 1, Iliac bone; 2, sacrum; 3, gluteal muscle; 4, piriformis muscle; 5, pelvic aponeurosis; 6, inferior gluteal plexus; 7, lumbosacral trunk; 8, first sacral root; 9, bladder.

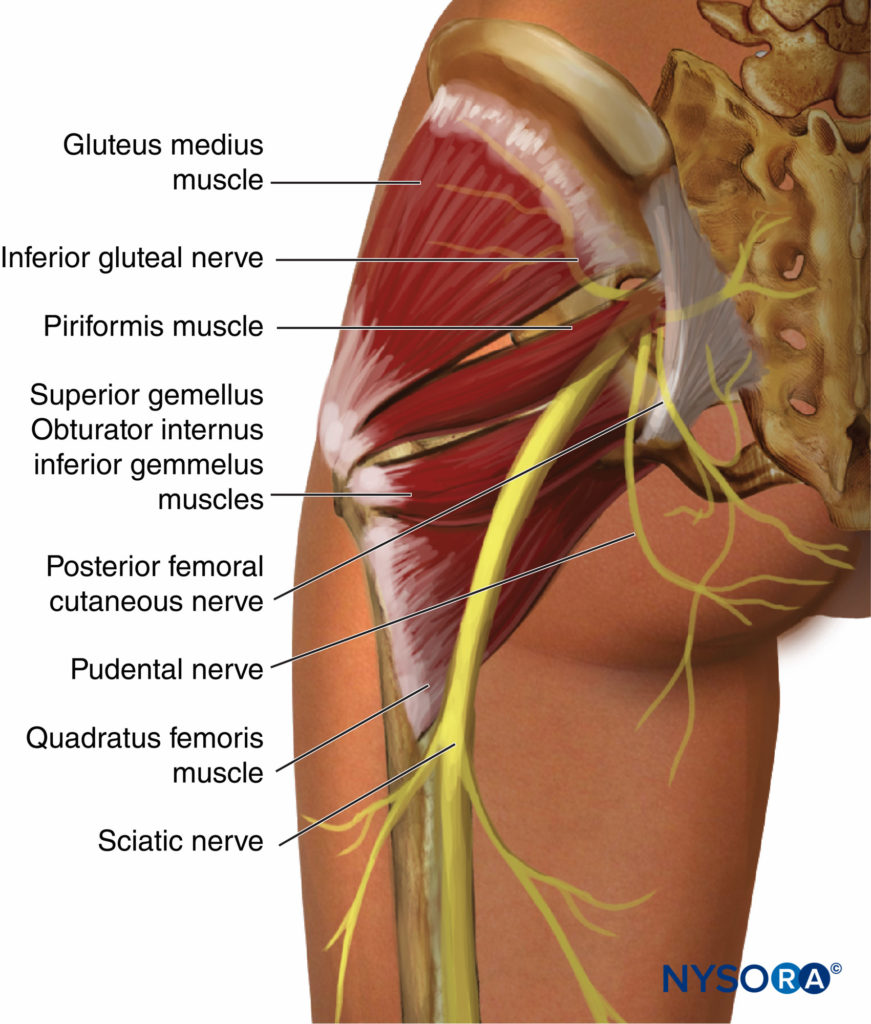

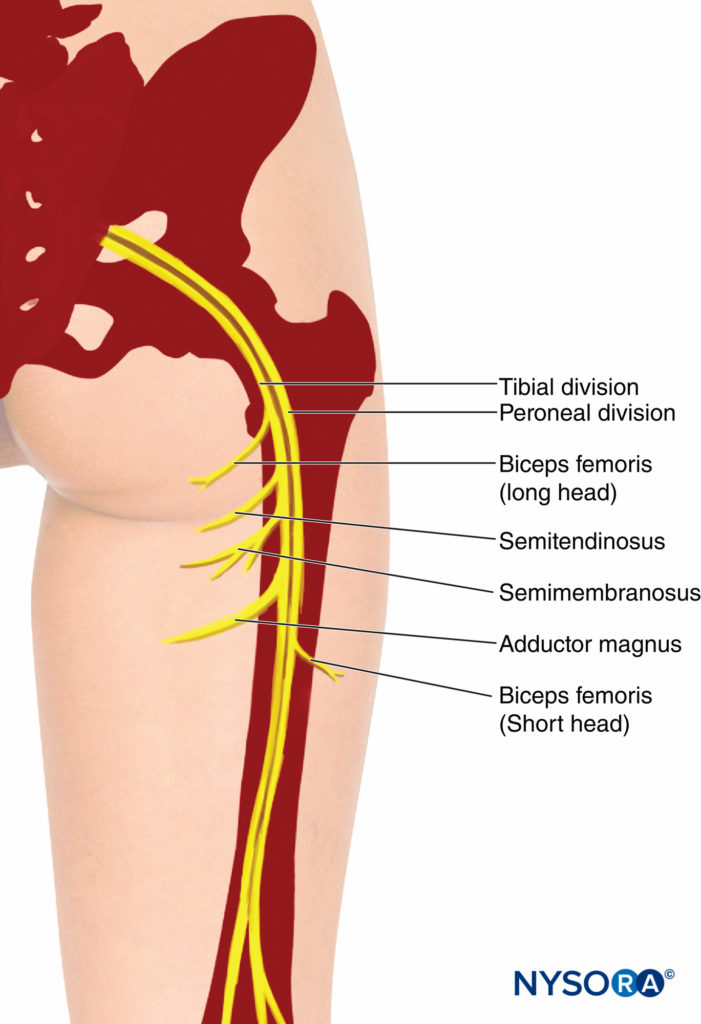

In the upper part of its course, the sciatic nerve lies deep in the gluteus maximus muscle and rests on the posterior surface of the ischium (Figures 3 and 4). The sciatic nerve crosses the external rotators, obturator internus, and gemelli muscles, then passes on to the quadratus femoris. The quadratus femoris separates the sciatic nerve from the obturator externus and the hip joint. Medially, the posterior cutaneous nerve of the thigh and the inferior gluteal plexus accompany the sciatic nerve, whereas more distally the sciatic nerve lies on the adductor magnus. The long head of the biceps femoris crosses the sciatic nerve obliquely. The articular branches of the sciatic nerve arise from the upper part of the nerve and supply the hip joint by perforating the posterior part of its capsule. However, the articular branches are sometimes derived directly from the sacral plexus. The muscular branches of the sciatic nerve innervate the gluteus, the biceps femoris, the ischial head of the adductor magnus, the semitendinosus, and the semimembranosus muscles (Figure 5; Table 1). The branches for the ischial head of the adductor magnus and semimembranosus muscles arise from a common trunk. The nerve to the short head of the biceps femoris comes from the common peroneal division, whereas the other muscular branches arise from the tibial division of the sciatic nerve.

FIGURE 5. Sciatic nerve. Downward course and motor branches to the hamstrings muscles.

TABLE 1. Branches, source, and motor innervation of the sacral plexus.

| Nerve | Source | Muscular Innervation |

|---|---|---|

| Nerve to obturator internus muscle | Lumbosacral trunk and S1 | Obturator internus |

| Superior gluteal nerve | Lumbosacral trunk and S1 | Gluteus medius Gluteus minimus Tensor fasciae lata |

| Nerve to piriformis muscle | S2 | Piriformis |

| Nerve to biceps femoris superior | Anterior portion of plexus | Biceps femoris superior |

| Nerve to biceps femoris inferior and quadratus femoris | Anterior portion of plexus | Biceps femoris inferior Quadratus femoris Branch to coxofemoral articulation |

| Posterior femoral cutaneous nerve (lesser sciatic nerve) | Lumbosacral trunk, S1, S2 | Inferior gluteal n. to gluteus maximus muscle Sensory branch to buttock, thigh, popliteal fossa, and lateral aspect of knee |

The parasacral area is delineated by the ventral aponeurosis of the piriformis muscle dorsally, by the pelvic aponeurosis medially, and by the aponeurosis of the obturator internis muscle laterally. The common peroneal component passes through the piriformis muscle or above it, and only the tibial component passes below the muscle.

The tibial and common peroneal elements of the sciatic nerve each have their own outer layer of epineurium. Both components are further enclosed by a dense layer of connective tissue, which runs from the origin of the sciatic nerve to its bifurcation. This layer has been given several names over the years, but lately it is commonly referred to as the “paraneural sheath” of the sciatic nerve. Injection of local anesthetic deep to this sheath (but outside the epineurium of the tibial or common peroneal nerves) has been shown to spread a considerable distance proximally and distally, and result in a rapid onset, dense block. This is not considered an “intraneural” injection as the injection occurs outside of the epineurium.

Choice of Local Anesthetic

Despite its large size, sciatic block requires a relatively low vol-ume of local anesthetic to achieve anesthesia of the entire trunk of the nerve. Generally, 20–25 mL of local anesthetic is sufficient. The choice of the type and concentration of local anesthetic should be based on whether the block is planned for surgical anesthesia or pain management (Table 2). When seeking prolonged pain relief, longer-acting local anesthetic may be more appropriate. Addition of epinephrine may be justified in patients undergoing above the knee amputation, in whom prolonged analgesia is desired.

TABLE 2. Local anesthetic choices for sciatic nerve block: duration of anesthesia and analgesia.

| Onset (min) | Anesthesia (h) | Analgesia (h) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3% 2-Chloroprocaine | 10–15 | 2 | 2.5 |

| 1.5% Mepivacaine | 10–15 | 4–5 | 5–8 |

| 2% Lidocaine | 10–20 | 5–6 | 5–8 |

| 0.5% Ropivacaine | 15–20 | 6–12 | 6–24 |

| 0.75% Ropivacaine | 10–15 | 8–12 | 8–24 |

| 0.5% Bupivacaine | 15–30 | 8–16 | 10–48 |

Equipment

As with all regional anesthesia techniques, the heart rate, blood pressure, and pulse oximetry are routinely monitored before performing the block. Resuscitation equipment and emergency medications must be immediately available and ready to use. Supplemental oxygen via face mask is routinely used before giving sedation. A standard regional anesthesia tray is prepared with the following equipment:

- Sterile towels and 4-in. × 4-in. gauze packs

- 20-mL syringe with local anesthetic

- Sterile gloves, marking pen, and surface electrode

- One 1.5 -in., 25-gauge needle for skin infiltration

- A 10-cm long, short-bevel, insulated stimulating needle (15 cm for anterior approach)

- Peripheral nerve stimulator

- Injection pressure monitor

Learn more about Equipment for Regional Anesthesia.

Interpreting Responses to Nerve Stimulation

Twitches of the hamstrings, calf, foot, or toes at 0.3–0.5 mA current all can be used as signs of successful localization of the sciatic plexus (nerve). Table 3 presents common responses to nerve stimulation and the course of action to take to obtain the proper response.

TABLE 3. Common responses to nerve stimulation and action to take.

| Response Obtained | Interpretation | Problem | Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Local twitch of the gluteus muscle | Direct stimulation of the gluteus muscle | Too shallow (superficial) placement of the needle | Continue advancing the needle |

| Needle contacts bone but local twitch of the gluteus muscle not elicited | Needle inserted close to the caudal aspect of the iliac bone or the lateral aspect of the sacrum | Too superior or too medial needle insertion | Slightly laterally and caudally redirect the needle |

| Needle encounters bone and sciatic twitches elicited | Needle missed the plane of the sciatic nerve and is stopped by the hip joint or ischial bone | Needle inserted too laterally (hip joint) or medially (ischial bone) | Withdraw the needle and redirect slightly medially or laterally (5–10 degrees) |

| Hamstring twitch | Stimulation of the main trunk of the sciatic nerve | None. These branches are within the sciatic nerve sheath at this level | Accept and inject local anesthetic |

| The needle placed deep (10 cm) but no twitches elicited and no bone contact | Needle has passed through the sciatic notch | Too inferior needle placement | Withdraw and redirect the needle slightly laterally, or cephalad |

| Paresthesia of the genital organs | Needle is stimulating the inferior roots of the sacral plexus (pudendal nerve) | Too inferior and too medial needle placement | Withdraw and redirect the needle slightly cephalad and laterally |

BLOCK DYNAMICS AND PERIOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Sciatic nerve block may cause patient discomfort because the needle passes through the gluteus muscles. Adequate sedation and analgesia are important to ensure patient comfort. Midazolam 2–4 mg can be given for patient positioning, and alfentanil 500–750 mcg is given just before needle insertion. A typical onset time for this block is 10–25 minutes, depending on the type, concentration, and volume of local anesthetic used. The first signs of block onset are usually reported by the patient as a feeling that the foot is “different” or that they cannot wiggle their toes.

NYSORA Tips

- Inadequate skin anesthesia despite an apparent timely onset of the block can occur. Local infiltration at the site of the incision by the surgeon is often all that is needed to allow the surgery to proceed.

POSTERIOR APPROACHES TO SCIATIC NERVE BLOCK

General Considerations

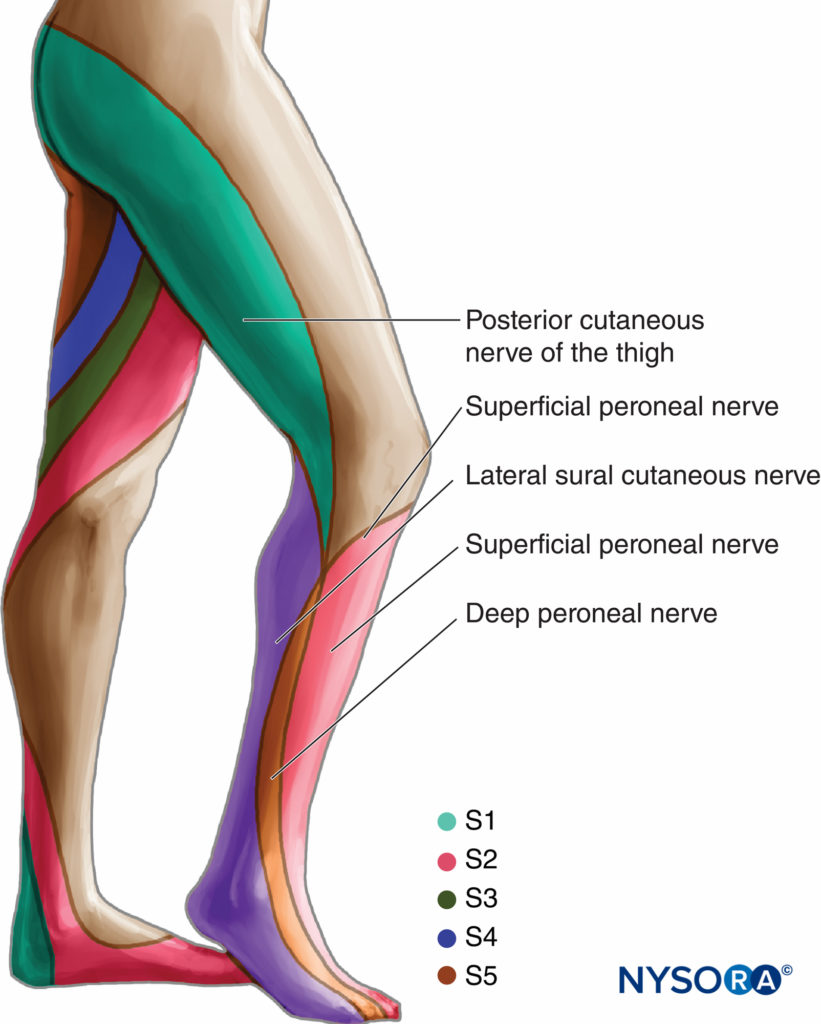

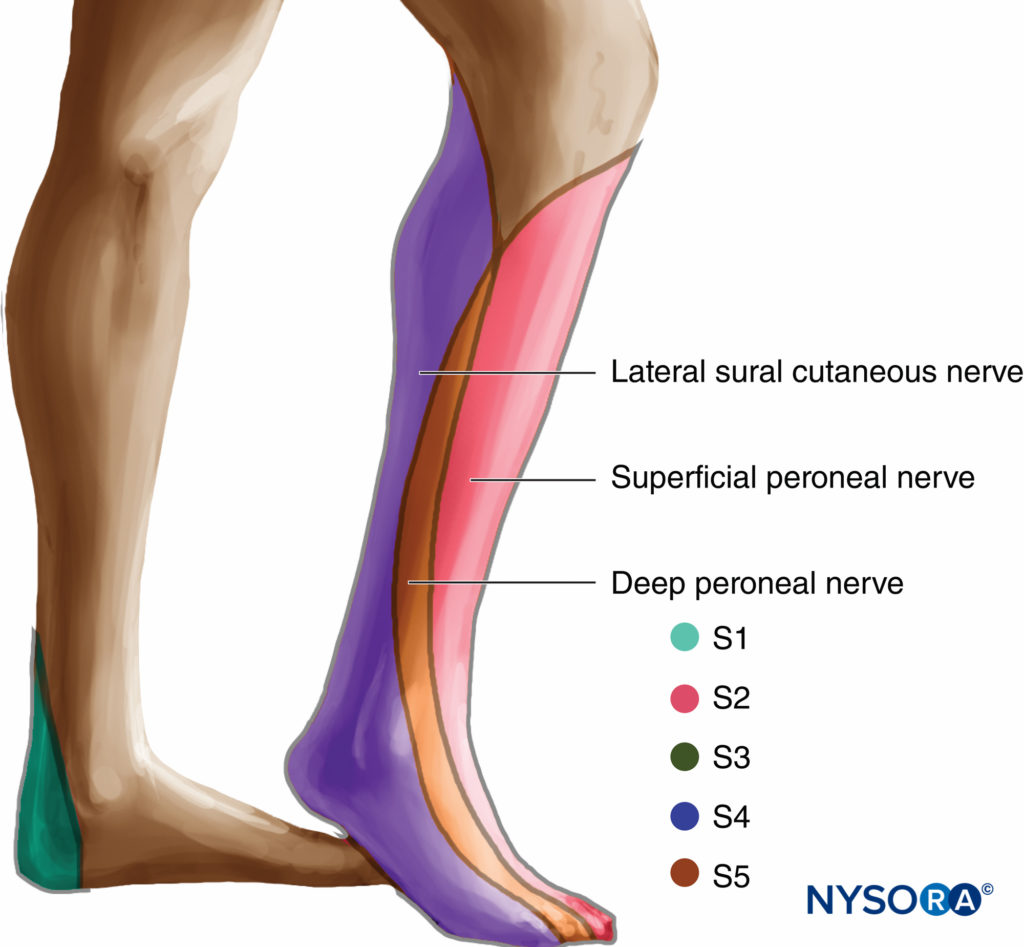

The posterior approach to sciatic block has wide clinical applicability for surgery and pain management of the lower extremity. The block require expertise with more basic nerve blocks for successful and safe practice. It is particularly well suited for surgery on the knee, calf, Achilles tendon, ankle, and foot. It provides complete anesthesia of the leg below the knee with the exception of the medial strip of skin, which is innervated by the saphenous nerve (Figure 6). When combined with a femoral nerve or lumbar plexus block, anesthesia of almost the entire leg can be achieved.

FIGURE 6. Sciatic nerve. Cutaneous innervation.

Distribution of Anesthesia

Sciatic nerve block results in anesthesia of the skin of the pos-terior aspect of the thigh, hamstrings, and biceps muscles, part of the hip and knee joints, and the entire leg below the knee, with the exception of the skin of the medial aspect of the lower leg (see Figure 6). Depending on the level of surgery, the addition of a saphenous or femoral nerve block may be required.

Classic Posterior Approach

Anatomic Landmarks

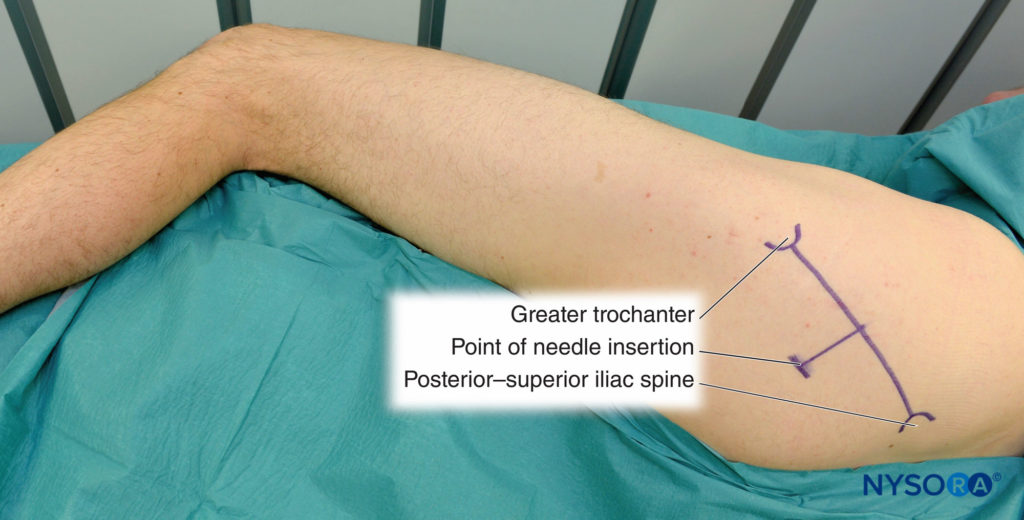

Landmarks for the posterior approach to sciatic block are easily identified in most patients (Figure 7). Proper palpation technique is of utmost importance because the adipose tissue over the gluteal area may obscure these bony prominences. The landmarks are outlined by a marking pen:

- Greater trochanter

- Posterior superior iliac spine

- Needle insertion site 4 cm distal to the midpoint between the two landmarks

FIGURE 7. Sciatic nerve block, posterior approach.

Technique

The patient is in the lateral decubitus position with a slight forward tilt–this prevents the “sag” of the soft tissues in the gluteal area and significantly facilitates block placement. The foot on the side to be blocked should be positioned over the dependent leg so that twitches of the foot or toes can be easily noted. After cleaning with an antiseptic solution, local anesthetic is infiltrated subcutaneously at the determined needle insertion site.

NYSORA Tips

- Raise the height of the bed enough and assume an ergo-nomic position to allow a comfortable and stable position for the patient during block placement and for observation of the motor responses to nerve stimulation.

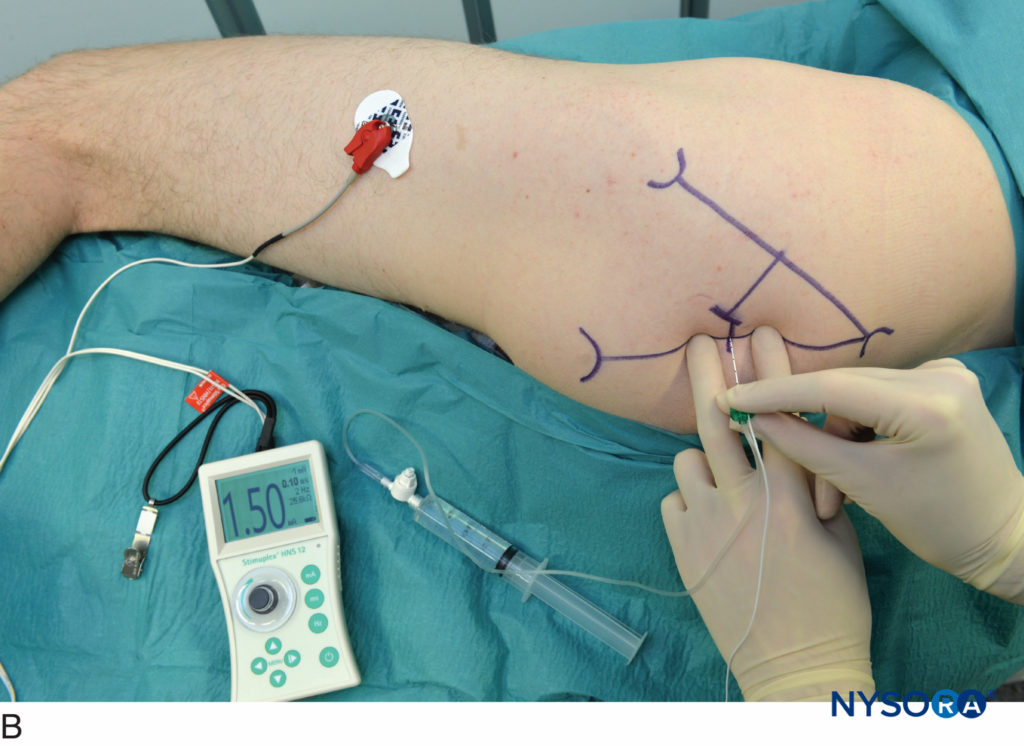

The fingers of the palpating hand should be firmly pressed on the gluteus muscle to decrease the skin–nerve distance (Figure 8). The palpating hand should not be moved during block placement; even small movements of the palpating hand can substantially change the position of the needle insertion site because the skin and soft tissues in the gluteal region are highly mobile. The needle is introduced at an angle perpendicular to the spherical skin plane (Figure 8A and B). The nerve stimulator should be initially set to deliver 1.0–1.5 mA current (2 Hz, 100 μsec) to allow detection of twitches of the gluteal muscles and stimulation of the sciatic nerve.

FIGURE 8. A and B. Sciatic nerve block, posterior approach. Needle insertion is in the perpendicular plane; the palpating hand is firmly pressed to decrease the skin–nerve distance and stabilize the anatomy.

As the needle is advanced, the first twitches observed are from the gluteal muscles. These twitches merely indicate that the needle position is still too shallow. The goal is to achieve visible or palpable twitches of the hamstrings, calf muscles, foot, or toes at 0.3–0.5 mA current. Twitches of the hamstrings are equally acceptable because this approach blocks the nerve proximal to the separation of the neuronal branches to the hamstrings muscle. Once the gluteal twitches disappear, brisk response of the sciatic nerve to stimulation is observed (ham-strings, calf, foot, or toe twitches). After the initial stimulation of the sciatic nerve is obtained, the stimulating current is gradually decreased until twitches are still seen or felt at 0.3–0.5 mA current. This typically occurs at a depth of 5–8 cm.After negative aspiration for blood, 15–25 mL of local anesthetic is injected (Figure 9). Any resistance to the injection of local anesthetic should prompt needle withdrawal by 1 mm. The injection is then reattempted. Persistent resistance to injections should prompt complete needle withdrawal and ensuring needle patency before reintroduction.

FIGURE 9. Sciatic nerve block, posterior approach. Dispersion of the local anesthetic after injection.

NYSORA Tips

- Since the level of the block with this approach is above the departure of the branches for hamstring muscles, twitch of any of the hamstring muscles can be accepted as a reliable sign of localization of the sciatic nerve without deliberately seeking foot response.

- When the first needle pass does not result in nerve localization, do not regard it as a failure. Instead, use a systematic approach to troubleshooting:

- Ascertain the nerve stimulator is functional, properly connected, and set to deliver the desired current.

- Mentally visualize the plane of the initial needle insertion, and redirect the needle in a slightly caudal direction (5–10 degrees) to the initial insertion plane.

- If the above maneuver fails, withdraw the needle to the skin and redirect it slightly cephalad (5–10 degrees) to the initial insertion plane.

- Failure to obtain hamstrings or foot response to nerve stimulation should prompt a reassessment of the landmarks and patient position.

Continuous Block

The continuous sciatic nerve block is an advanced regional anesthesia technique, and experience with the single-shot technique is recommended to ensure its efficacy and safety. Continuous sciatic nerve block was described by Gross in 1956. The current technique used is similar to the single-shot injection; however, slight angulation of the needle in the caudal direction is necessary to facilitate threading of the catheter. Securing and maintenance of the catheter are easy and convenient. This technique can be used for surgery and postoperative pain management in patients undergoing a wide variety of lower leg, foot, and ankle surgeries. Perhaps the single most important indication for use of this block is for amputation of the lower extremity.

Technique

Patient positioning, marking of landmarks, skin preparation and local anesthetic infiltration are performed as described above. An 8–10 cm long, insulated stimulating needle (preferably Tuohy-style tip) is inserted in the same manner as for the single-injection technique. The opening of the needle should face distally (pointing toward the patient’s foot) to facilitate catheter insertion.

NYSORA Tips

- When insertion of the catheter proves difficult, lowering the angle of the needle can be helpful.

- It is useful to inject some local anesthetic intramuscularly to prevent pain on advancement of larger gauge and blunt-tipped needles typically used for this block.

After obtaining the motor response at a current of 0.3–0.5 mA, a 20-mL bolus of local anesthetic is injected. This is followed by insertion of the catheter 5 cm beyond the needle tip (Figure 10). The catheter is then aspirated to check for inadvertent intravascular placement.

A number of techniques to secure the catheter to the skin have been proposed. A benzoin skin preparation followed by application of a clear dressing and a cloth tape is one such simple and efficacious method. The infusion port should be clearly marked as “continuous sciatic block.”

FIGURE 10. Continuous sciatic nerve block, posterior approach. Shown is the course of the catheter (1) and the fusiform-shaped contrast area indicating the spread of the local anesthetic in the sheath of the sciatic nerve (2). In this example, a mere 2 mL of the local anesthetic is injected.

Continuous Infusion

Continuous infusion is always initiated after an initial bolus of dilute local anesthetic through the catheter. Ropivacaine 0.2% is commonly used for this purpose (15–20 mL). Diluted solutions of bupivacaine or L-bupivacaine are also suitable, but can result in undesirably greater motor block. The infusion is initiated at 10 mL/h or 5 mL/h when a patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) dose is planned (5 mL).

Parasacral Approach

Described by Mansour in 1993, the parasacral sciatic nerve block is well suited for continuous infusion of local anesthetic. In addition, this block has characteristics of a plexus block and yields anesthesia of the entire sacral plexus, and obturator nerve. Ripart reported a 94% success rate in his series of 400 parasacral sciatic nerve block cases. The parasacral approach to sciatic block has a wide clinical applicability for surgery and pain management of the lower extremity, particularly when combined with a femoral or psoas compartment block. This technique is associated with a high success rate and is particularly well suited for surgery on the popliteal fossa and the knee.

Distribution of Anesthesia

Parasacral sciatic nerve block results in anesthesia of the skin of the posterior thigh, hamstrings, and biceps femoris muscles; part of the hip and knee joint; and the entire leg below the knee except the medial cutaneous skin of the lower leg (see Figure 6). Morris demonstrated extension of anesthesia to the obturator nerve after sciatic nerve block, as tested by the presence of adductor muscle weakness on a numeric scale. Jochum however, suggested that the obturator nerve is sporadically affected by the parasacral sciatic nerve block.

Anatomic Landmarks

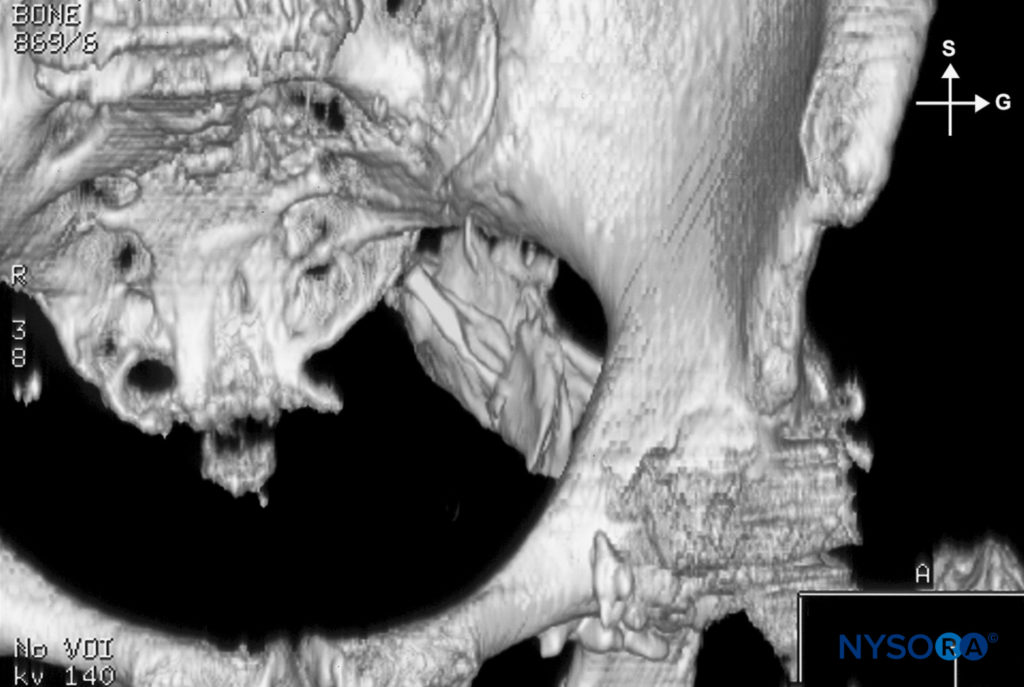

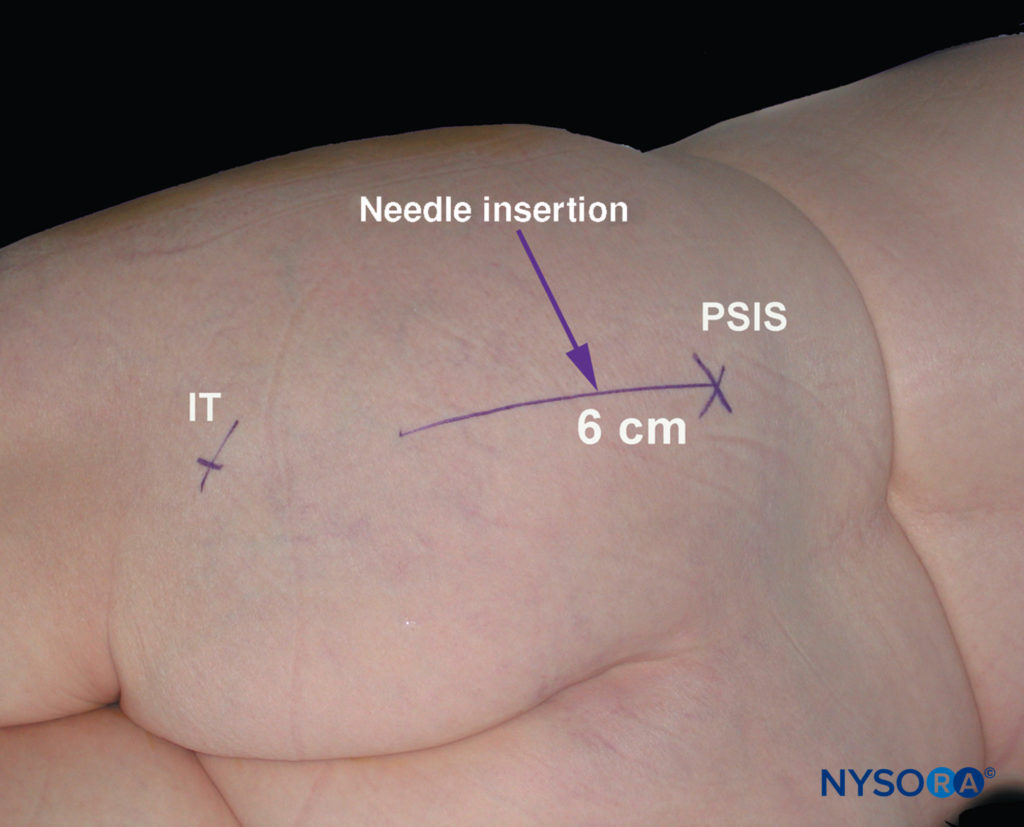

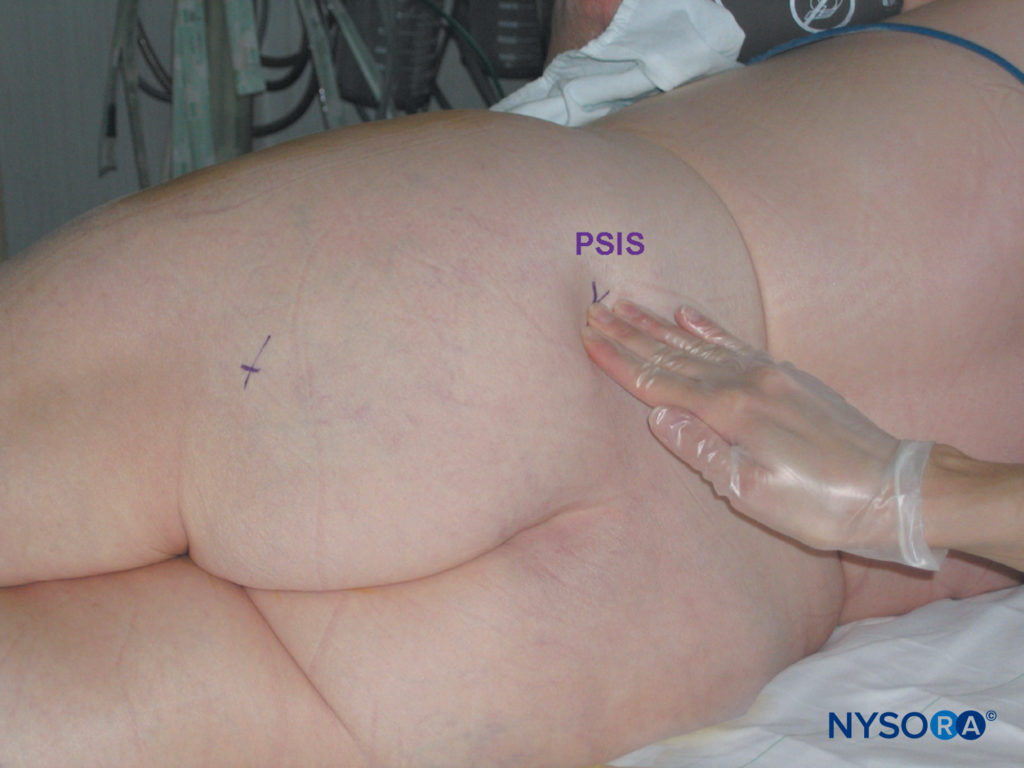

Landmarks for the parasacral approach to sciatic block are easily identified in most patients (Figure 11). Careful palpation technique is important because the adipose tissue over the gluteal area may obscure these bony prominences (Figures 12 and 13). The following landmarks are outlined by a marking pen:

- Posterior–superior iliac spine (PSIS)

- Ischial tuberosity (IT)

- A line between the PSIS and the IT is drawn. The needle insertion point lies 6 cm caudad to the PSIS on this line. The insulated needle is inserted at this point and advanced in a sagittal plane.

FIGURE 11. Parasacral approach to sciatic nerve block. Shown are the posterior superior iliac spine (PSIS) and the ischial tuberosity (IT). The needle insertion site is marked as 6 cm caudad to the PSIS on the line connecting PSIS with IT

FIGURE 12. Parasacral sciatic nerve block. Palpation technique to identify posterior superior iliac spine (PSIS).

FIGURE 13. Parasacral sciatic nerve block. Proper palpation technique to identify the ischial tuberosity. (IT, ischial tuberosity; PSIS, posterior superior iliac spine.)

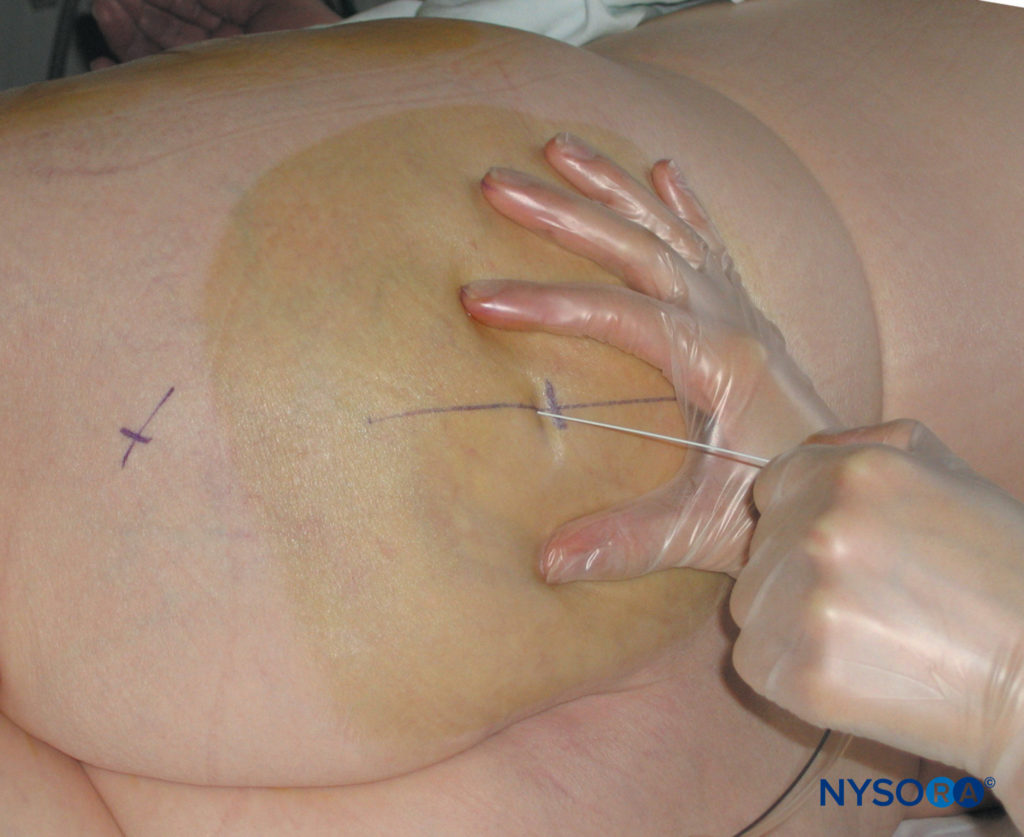

Technique

The patient is positioned in a lateral decubitus position, similar to the position required for the classic posterior approach to sciatic block (Figure 13). The dependent limb is kept straight while the limb to be blocked is flexed at both the hip and knee. Appropriate sedation and analgesia are mandatory to ensure the patient’s comfort throughout the procedure. After cleaning with an antiseptic solution, local anesthetic is infiltrated subcutaneously at the determined needle insertion site.

- Contact with the bone usually indicates the needle contact with the wings of the sacrum or the iliac bone, superior to and near the greater sciatic notch.

- In this case, the needle is withdrawn and redirected slightly caudally and laterally.

- Contact with the bone can be used as a depth test. The needle depth is noted; the needle should not be advanced more than 2 cm beyond this depth. At this site, the sciatic nerve is approached at the top of the greater sciatic foramen while leaving the pelvis. Advancing the needle deeper may expose pelvic viscera and vessels to risk of injury.

FIGURE 14. Parasacral sciatic nerve block. Needle insertion is perpendicular to the horizontal plane.

The needle is inserted perpendicular to the skin and advanced slowly (Figure 14). The motor response of the sciatic plexus is usually obtained at a depth between 6 and 8 cm. The goal is to achieve visible or palpable twitches of the hamstrings, calf muscles, foot, or toes at the current intensity of 0.3–0.5 mA. The distal motor response may be either a tibial or a peroneal response—it is not necessary to stimulate both components (Figure 15). Twitches of the hamstrings are equally acceptable because this approach blocks the sciatic nerve proximal to the separation of the neuronal branches to the hamstring muscles.

FIGURE 15. Sciatic nerve stimulation: motor response of the common peroneal and tibial nerves indicate proper localization of the sciatic nerve.

Once an appropriate response is obtained, 20-25 mL of local anesthetic is injected slowly with intermittent aspiration (Figure 16).

Cuvillon et al. compared the parasacral sciatic nerve block with Winnie’s approach with one or two stimulations. Winnie’s approach using the double-injection technique required more time to perform the block compared with Winnie’s single-injection technique and the parasacral method. Although the onset of sensory and motor blocks were significantly faster with the double-injection method, the additional time needed to perform the double-injection block eliminated the advantage of the faster onset.

FIGURE 16. Parasacral nerve block: dispersion of the contrast after injection, the “negative” contrast sign, and a typical fusiform distribution of the injectate.

Continuous Parasacral Sciatic Nerve Block

The continuous parasacral sciatic nerve block is similar to the single-shot injection; however, slight caudal angulation of the needle is necessary to facilitate threading of the catheter. Securing and maintenance of the catheter are easy and convenient. This technique can be used for surgery and postoperative pain management in patients undergoing a wide variety of knee, lower leg, foot, and ankle surgeries. The technique is identical to the single injection technique, except a continuous-block needle is used (Figure 17). The opening of the needle should face distally to facilitate catheter insertion. The initial intensity of the stimulating current should be 1.0–1.5 mA.

FIGURE 17. Equipment for continuous sciatic block

NYSORA Tips

- It is useful to inject some local anesthetic intramuscularly to decrease pain during placement of the continuous nerve block needle.

After obtaining the motor response at 0.3–0.5 mA, a 20 mL bolus of local anesthetic is injected and the catheter inserted 3-5 cm beyond the needle tip. If confirmation of catheter placement is desired, contrast media can be injected through the catheter and radiographic images can be studied. The presence of a spindle 2–3 cm in length with an oblique orientation crossing the sciatic notch on the anteroposterior radiograph and/or shadowing of the sacral roots are considered to indicate injection into the correct plane and adequate placement of the catheter (see Figure 18). After securing the catheter, an infusion (e.g., ropivacaine 0.2% at 5 mL/hr with 5 mL/q60min patient-controlled bolus) is initiated.

FIGURE 18. Parasacral sciatic block: shown is the course of the catheter and visualization of the injectate around the sciatic nerve.

ALTERNATIVE POSTERIOR APPROACHES

Di Benedetto described a subgluteal approach to the sciatic nerve block in 2002. This technique is a good alternative to the more proximal approaches to the sciatic nerve, with the potential for reducing the discomfort experienced by the patient dur-ing block placement. The landmarks with the subgluteal approach are the greater trochanter of the femur, the ischial tuberosity, and a line between the two with the midpoint marked. From the midpoint, another line is drawn perpendicularly and extended 4 cm in the caudal direction to identify the needle insertion point. A 20-gauge, 10-cm needle and nerve stimulator are used for this approach, and 20 mL of local anesthetic is injected when twitches of the sciatic nerve are obtained at ≤0.5 mA current.

Of note, ultrasound-guided subgluteal approach to sciatic block has become one of the most common sciatic nerve block techniques in modern regional anesthesia. Traditional approaches to the sciatic nerve at the pelvic level require identification of pelvic bone structures. Although the size of the buttocks is vari-able among different individuals and in the same individual over time, the relation of the sciatic nerve to the pelvis is constant throughout life. Using this premise, Franco has suggested a more simplified approach to the sciatic nerve block that does not require palpation of deep bony structures. The landmarks with this approach are the midline of the intergluteal sulcus, and a point 10 cm lateral to the midline of the intergluteal sulcus where the block needle will be inserted. The curvature of the buttocks is disregarded when locating the needle insertion point. Care must be taken not to stretch the soft tissues when marking the needle insertion site as subsequent recoil of the tissues will occur, causing the distance to the nerve to be underestimated. The patient is either in the prone or lateral position and the needle is inserted parallel to the midline.

Complications in Posterior Approaches and How to Avoid Them

Table 4 lists instructions on possible complications of sciatic nerve block and methods to decrease the risk.

TABLE 4. Complications and how to avoid them.

| Infection | Use strict aseptic technique |

| Hematoma | Avoid multiple needle insertions, particularly in anticoagulated patients |

| Vascular puncture | Avoid deep needle insertion (pelvic vessels) |

| Local anesthetic toxicity | Avoid using large volumes and doses of local anesthetic owing to the proximity of the large vessels and the potential for rapid absorption Injection of local anesthetic should be carried out slowly and with frequent aspiration to rule out intravascular injection |

| Nerve injury | Sciatic nerve has a unique predisposition for mechanical and pressure injury Use nerve stimulation and slow needle advancement Never inject local anesthesia when the patient complains of pain or when abnormally high pressure on injection is noted Never assume that the needle is obstructed with tissue debris when resistance to injection is met When stimulation is obtained with a current intensity of <0.2 mA, withdraw the needle slightly to obtain the same response with a current intensity of >0.2 mA before injecting local anesthetic |

| Nerve injury | Advance the needle slowly when twitches of the gluteus muscle cease to avoid impaling the sciatic nerve on a rapidly advancing needle |

| Other | Instruct the patient and nursing staff on the care of the insensate extremity Explain the need for frequent body repositioning to avoid stretching and prolonged ischemia (sitting) on the anesthetized sciatic nerve Advise heel padding during prolonged bed rest or sleep to prevent pressure sores from developing |

| Perforation of pelvic organs | Directing the needle medially should be exercised with this complication in mind |

| Anesthesia of the pudendal nerve | The pudendal nerve, a branch of the sacral plexus, may be anesthetized by the parasacral nerve block owing to diffusion of the injected local anesthesia Inform patients that this problem is transient |

| Tourniquet | Injection of the local anesthetic within the sciatic nerve sheath, epinephrine, and a tourniquet over the site of injection all can combine to cause ischemia of the sciatic nerve |

ANTERIOR APPROACH

General Considerations

The anterior approach to a sciatic block is an advanced nerve block technique. The block is suited for surgery on the leg below the knee, particularly on the ankle and foot. It provides complete anesthesia of the leg below the knee with the exception of the medial strip of skin innervated by the saphenous nerve (Figure 19). When combined with a femoral nerve block, anesthesia of the entire knee and lower leg is achieved. The anterior approach is much less clinically applicable than posterior approaches because the distribution of anesthesia is more limited and a higher level of skill is required. In addition, this technique is not suitable for catheter insertion because of the deep location and perpendicular angle of needle insertion required to reach the sciatic nerve. Consequently, this block is best reserved for patients who cannot easily be moved to the lateral position needed for the posterior approach; e.g., patients with spinal injuries or under general anesthesia.

FIGURE 19. Distribution of anesthesia with anterior approach to sciatic nerve block

Since the original description by Beck several clinicians have attempted to devise more reliable landmarks and tech-nique for this block. However, all described approaches derive the needle insertion site at nearly identical points regardless of whether they use bony prominences, soft tissue, or femoral artery as landmarks. In addition, even if these different approaches varied slightly in the site of needle insertion, the long path by the needle required to reach the sciatic nerve (8–12 cm) and the tendency of long, blunt-tipped needles to bend on insertion through the tissues make any such differences meaningless when it comes to increasing the precision of the technique.

Equipment

A standard regional anesthesia tray is prepared with the following equipment:

- Sterile towels and 4-in.× 4-in. gauze packs

- 20-mL syringes with local anesthetic

- Sterile gloves, marking pen, and surface electrode

- One 1.5-in., 25-gauge needle for skin infiltration

- A 15-cm long, short-bevel, insulated stimulating needle

- Peripheral nerve stimulator

Learn more about Equipment for Regional Anesthesia.

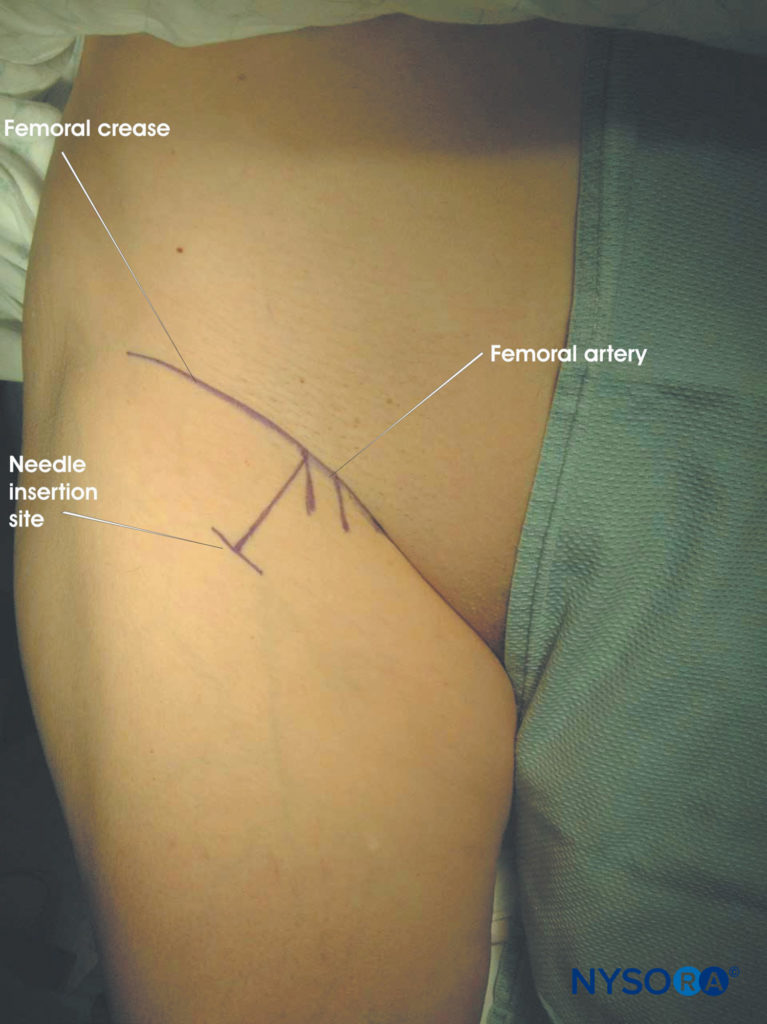

Anatomic Landmarks

The following landmarks should routinely be outlined using a marking pen (Figure 20):

- Femoral crease

- Femoral artery pulse

- Needle insertion point marked 4–5 cm distally on the line passing through the pulse of the femoral artery and perpendicular to the femoral crease

FIGURE 20. Sciatic nerve block through the anterior approach.

Technique

The leg is fully extended on the table with the patient in the supine position. After cleaning the area with an antiseptic solution, local anesthetic is infiltrated subcutaneously at the needle insertion site. The fingers of the palpating hand should be firmly pressed against the quadriceps muscle to decrease the skin–nerve distance. The block needle (connected to a nerve stimulator set to deliver a current of 1.5 mA) is introduced at a perpendicular angle to the skin plane (Figure 21). Motor response of the sciatic nerve is typically obtained at a depth of 8–12 cm. Acceptable responses are visible or palpable twitches of the calf muscles, foot, or toes at a current of 0.3–0.5 mA. After negative aspiration for blood, 20 mL of local anesthetic is slowly injected. If high injection pressure is detected, the needle should be withdrawn by 1 mm and injection attempted again. If high injection pressure persists, the needle should be withdrawn and flushed prior to further attempts.

FIGURE 21. Sciatic nerve block through the anterior approach. Needle insertion.

NYSORA Tips

- Local twitches of the quadriceps muscle are often elicited during needle advancement. The needle should be advanced past these twitches.

- Although there is a concern of femoral nerve injury with further needle advancement, at this level, the femoral nerve is divided into smaller terminal branches that are movable and unlikely to be penetrated by a slowly advancing, blunt-tipped needle.

- Resting the patient’s heel on the bed surface may prevent the foot from twitching even when the sciatic nerve is stimulated. This can be prevented by placing the ankle on a footrest or by having an assistant continuously palpate the calf or Achilles tendon.

- Because branches to the hamstring muscle may depart the main trunk of the sciatic nerve at the level of needle insertion, twitches of the hamstrings should not be accepted as a reliable sign of sciatic nerve localization.

Bone contact is frequently encountered during needle advancement. This indicates that the needle has contacted the femur (usually lesser trochanter). In this case, the foot is first rotated laterally, which should swing the lesser trochanter out of the path of the needle and allow deeper advancement of the needle and nerve localization. If this maneuver fails, the needle is redirected slightly medially or reinserted more medially. Table 5 lists some common responses to nerve stimulation and the course of action to take to obtain the proper response.

TABLE 5. Interpreting responses to nerve stimulation.

| Response Obtained | Interpretation | Problem | Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Twitch of the quadriceps muscle (patella twitch) | Common; stimulation of the branches of the femoral nerve | Too shallow (superficial) placement of needle | Continue advancing the needle |

| Local twitch at the femoral crease area | Direct stimulation of the iliopsoas or pectineus muscles | Too superior insertion of needle | Stop the procedure and reassess the landmarks |

| Hamstring twitch | Needle may be stimulating branch(es) of the sciatic nerve to the hamstring muscle; direct stimulation of the hamstrings with higher current is also possible | Unreliable-difficult to determine whether the needle is in the proximity of the sciatic nerve | Withdraw the needle and redirect slightly medially or laterally (5–10 degrees) |

| The needle is placed deep (12–15 cm) but twitches were not elicited and bone is not contacted | The needle is likely too medial | Withdraw and redirect slightly laterally | |

| Twitches of the calf, foot, or toes | Stimulation of the sciatic nerve | None | Accept and inject local anesthetic |

SUMMARY

Although the sciatic nerve block was described in 1920, many practitioners avoided this block because of its perceived complexity. Sciatic nerve block is an important technique for the regional anesthesiologist to master because the combination of this block and a femoral nerve block or lumbar plexus block can anesthetize almost the entire leg. Although the posterior sciatic nerve block has an intermediate level of difficulty, with practice and knowledge of anatomy, high success rates can be achieved. Many approaches have been proposed; the most relevant have been presented in this chapter. Finally, nearly all described approaches are similar in clinical efficacy; therefore, learning one single approach well is recommended as this would suffice for most clinical indications.

REFERENCES

- Sherwood-Dunn B: Regional Anesthesia: (Victor Pauchet’s Technique). Philadelphia, PA: Davis, 1921.

- Labat G: Regional Anesthesia: Its Technic and Clinical Application. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders, 1924.

- Côté AV, Vachon CA, Horlocker TT: From Victor Pauchet to Gaston Labat: The Transformation of Regional Anesthesia from a Surgeon’s Practice to the Physician Anesthesiologist. Anesth Analg 2003;96(4): 1193-1200.

- Winnie AP: Regional anesthesia. Surg Clin North Am 1975;55: 861–892.

- Beck GP: Anterior approach to sciatic nerve block. Anesthesiology 1963;24:222–224.

- Raj PP, Parks RI, Watson TD, Jenkins MT: A new single-position supine approach to sciatic-femoral nerve block. Anesth Analg 1975;54: 489–493.

- di Benedetto P, Bertini L, Casati A, et al: A new posterior approach to the sciatic nerve block: a prospective, randomized comparison with the classic posterior approach. Anesth Analg 2001;93:1040–1044.

- Cuvillon P, Ripart J, Jeannes P, et al: Comparison of the parasacral approach and the posterior approach, with single- and double-injection techniques, to block the sciatic nerve. Anesthesiology 2003;98:1436–1441.

- Mansour NY, Bennetts FE: An observational study of combined continuous lumbar plexus and single-shot sciatic nerve blocks for post-knee surgery analgesia. Reg Anesth 1996;21:287–291.

- Babinski MA, Machado FA, Costa WS: A rare variation in the high division of the sciatic nerve surrounding the superior gemellus muscle. Eur J Morphol 2003;41:41–42.

- Vloka JD, Hadzic A, April EW, et al: Division of the sciatic nerve in the popliteal fossa and its possible implications in the popliteal nerve block. Anesth Analg 2001;92:215–217.

- Andersen HL, Andersen SL, Tranum-Jensen J: Injection inside the paraneural sheath of the sciatic nerve: direct comparison among ultrasound imaging, macroscopic anatomy, and histologic analysis. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2012;37:410–413. 1

- Vloka JD, Hadzić A, Lesser JB: A common epineural sheath for the nerves in the popliteal fossa and its possible implications for sciatic nerve block. Anesth Analg. 1997;84:387–390.

- Franco CD: Connective tissues associated with peripheral nerves. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2012;37:363–365.

- Smith BE, Siggins D: Low volume, high concentration block of the sciatic nerve. Anaesthesia 1988;43:8–11.

- Sinnott CJ, Strichartz GR: Levobupivacaine versus ropivacaine for sciatic nerve block in the rat. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2003;28:294–303.

- Eledjam JJ, Ripart J, Viel E: Clinical application of ropivacaine for the lower extremity. Curr Top Med Chem 2001;1:227–231.

- Casati A, Fanelli G, Borghi B, Torri G: Ropivacaine or 2% mepivacaine for lower limb peripheral nerve blocks. Study Group on Orthopedic Anesthesia of the Italian Society of Anesthesia, Analgesia, and Intensive Care. Anesthesiology 1999;90:1047–1152.

- Hadzic A, Vloka J: Peripheral Nerve Blocks: Principles and Practice. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill, 2004.

- Bruelle P, Muller L, Bassoul B, Eledjam JJ: Block of the sciatic nerve. Cah Anesthesiol 1994;42:785–791.

- Dalens B, Tanguy A, Vanneuville G: Sciatic nerve blocks in children: comparison of the posterior, anterior, and lateral approaches in 180 pediatric patients. Anesth Analg 1990;70:131–137.

- Gross G: Continuous sciatic nerve block. Br J Anaesth 1956;28: 373–376.

- Ilfeld BM, Thannikary LJ, Morey TE, et al: Popliteal sciatic perineural local anesthetic infusion: a comparison of three dosing regimens for postoperative analgesia. Anesthesiology 2004;101:970–977.

- di Benedetto P, Casati A, Bertini L: Continuous subgluteus sciatic nerve block after orthopedic foot and ankle surgery: comparison of two infusion techniques. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2002;27:168–172.

- Mansour NY: Reevaluating the sciatic nerve blocK: another landmark for consideration. Reg Anesth 1993;18:322–323.

- Morris GF, Lang SA: Continuous parasacral sciatic nerve block: two case reports. Reg Anesth 1997;22:469–472.

- Morris GF, Lang SA, Dust WN, Van der Wal M: The parasacral sciatic nerve block. Reg Anesth 1997;22:223–228.

- Ripart J, Cuvillon P, Nouvellon E, et al: Parasacral approach to block the sciatic nerve: a 400-case survey. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2005;30:193–197.

- Bertini L, Borghi B, Grossi P, et al: Continuous peripheral block in foot surgery. Minerva Anestesiol 2001;67:103–108.

- di Benedetto P, Borghi B, Ricci A, van Oven H: Loco-regional anaesthesia of the lower limbs. Minerva Anestesiol 2001;67:56–64.

- Ho AM, Karmakar MK: Combined paravertebral lumbar plexus and parasacral sciatic nerve block for reduction of hip fracture in a patient with severe aortic stenosis. Can J Anaesth 2002;49:946–950.

- Jochum D, Iohom G, Choquet O, et al: Adding a selective obturator nerve block to the parasacral sciatic nerve block: an evaluation. Anesth Analg 2004;99:1544–1549.

- Bailey SL, Parkinson SK, Little WL, Simmerman SR: Sciatic nerve block. A comparison of single versus double injection technique. Reg Anesth 1994;19:9–13.

- Gaertner E, Lascurain P, Venet C, et al: Continuous parasacral sciatic block : a radiographic study. Anesth Analg 2004;98:831–834.

- Bendtsen TF, Lönnqvist PA, Jepsen KV: Preliminary results of a new ultrasound-guided approach to block the sacral plexus: the parasacral parallel shift. Br J Anaesth. 2011;107:278–280.

- Souron V, Eyrolle L, Rosencher N: The Mansour’s sacral plexus block: an effective technique for continuous block. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2000;25:208–209.

- Chelly J, Fanelli G, Casati A (eds): Continuous Peripheral Nerve Blocks : an Illustrated Guide. St. Louis, MO: Mosby, 2001.

- di Benedetto P, Casati A, Bertini L, Fanelli G: Posterior subgluteal approach to block the sciatic nerve: description of the technique and initial clinical experiences. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2002;19:682–686.

- Franco CD: Posterior approach to the sciatic nerve in adults: is euclidean geometry still necessary? Anesthesiology 2003;98:723–728.

- Magora F, Pessachovitch B, Shoham I: Sciatic nerve block by the anterior approach for operations on the lower extremity. Br J Anaesth 1974; 46:121–123.

- McNicol LR: Anterior approach to sciatic nerve block in children: loss of resistance or nerve stimulator for identifying the neurovascular compartment. Anesth Analg 1987;66:1199–1200.

- McNicol LR: Sciatic nerve block for children. Sciatic nerve block by the anterior approach for postoperative pain relief. Anaesthesia 1985;40: 410–414.

- Mansour NY: Anterior approach revisited and another new sciatic nerve block in the supine position. Reg Anesth 1993;18:265–266.

- Chelly JE, Delaunay L: A new anterior approach to the sciatic nerve block. Anesthesiology 1999;91:1655–1660.

- Vloka JD, Hadzic A, April E, Thys DM: Anterior approach to the sciatic nerve block: the effects of leg rotation. Anesth Analg 2001;92:460–462.

- Van Elstraete AC, Poey C, Lebrun T, Pastureau F: New landmarks for the anterior approach to the sciatic nerve block: Imaging and clinical study. Anesth Analg 2002;95:214–218.

- Hadzic A, Vloka JD: Anterior approach to sciatic nerve block. In: Hadzic A, Vloka J (eds): Peripheral Nerve Blocks. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill, 2004.