Chronic postsurgical pain (CPSP) is a serious yet often underestimated consequence of surgery. Affecting up to 60% of adults, depending on the type of operation, CPSP significantly impairs quality of life, functional recovery, and psychological health. In response to this pressing issue, the concept of transitional pain services (TPS) emerged in 2014. TPS is a comprehensive, multidisciplinary strategy designed to bridge acute postoperative care and long-term recovery, aiming to prevent the development of chronic pain.

A recent scoping review published in Anesthesiology assessed the global implementation and effectiveness of TPS programs. It offers a detailed analysis of existing research, highlighting the promise and challenges of TPS in clinical practice.

What is a transitional pain service (TPS)?

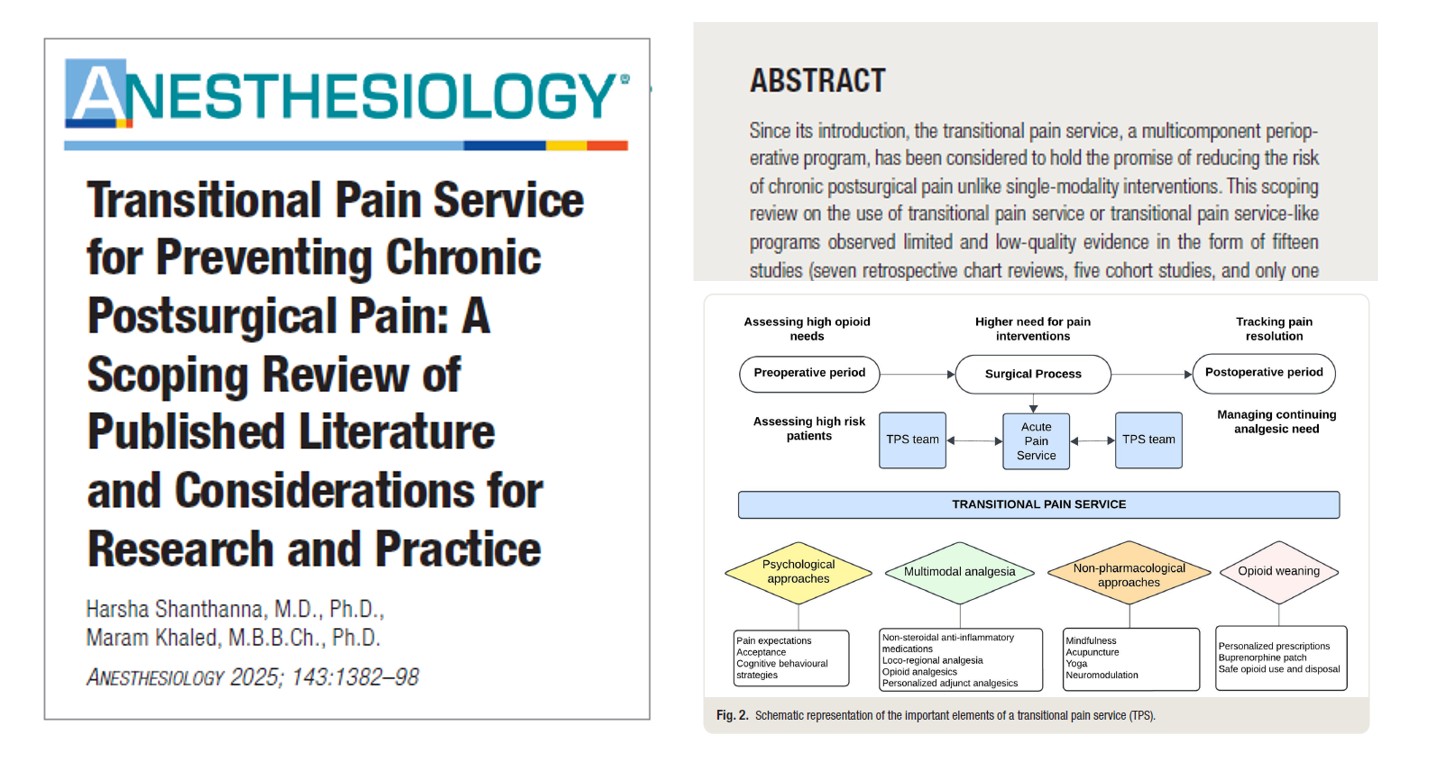

TPS is a multicomponent, patient-centered perioperative program that integrates care across the surgical timeline; before, during, and after surgery. The primary objectives are:

- To prevent the progression from acute to chronic pain

- To reduce prolonged opioid use

- To improve postoperative recovery and psychological outcomes

Core components of TPS include:

- Patient education and expectation setting

- Psychological support (e.g., cognitive behavioral therapy, mindfulness, acceptance and commitment therapy)

- Multimodal analgesia

- Opioid tapering strategies

- Longitudinal follow-up, often beyond hospital discharge

TPS teams typically consist of anesthesiologists, pain specialists, psychologists, nurses, physiotherapists, and coordinators, ensuring a holistic approach.

Key findings from the scoping review

This review analyzed 15 studies involving 7,981 patients across various countries and surgical specialties.

Study characteristics:

- 7 retrospective chart reviews

- 5 prospective cohort studies

- 1 randomized controlled trial (RCT)

- 2 mixed design studies

- Most studies focused on orthopedic, transplant, and spine surgeries

Major outcomes assessed:

- Postoperative opioid consumption

- Pain intensity and interference

- CPSP incidence (only 1 study assessed this as a secondary outcome)

What did the review reveal?

1. Evidence on CPSP prevention is very limited

- Only one RCT assessed CPSP directly and found no significant difference between TPS and standard care.

- The certainty of evidence regarding TPS preventing CPSP was rated very low due to:

- Limited sample sizes

- Methodological weaknesses

- Heterogeneous outcome definitions

2. Stronger evidence supports reduced opioid use

- 14 of 15 studies reported reductions in opioid use:

- Lower morphine equivalent doses

- Fewer opioid prescriptions at discharge

- Reduced prolonged opioid use

- Some studies showed complete opioid cessation in a substantial number of patients

3. Improvements in psychological outcomes

- Studies reported reductions in:

- Pain interference

- Catastrophizing

- Depression and anxiety

- However, positive patient engagement was key; patients with negative TPS experiences saw little or no improvement

Step-by-step: how a TPS program works

- Preoperative phase

- Risk assessment (opioid use, anxiety, pain history)

- Patient education and psychological prep

- Personalized pain management plan

- Intraoperative phase

- Use of regional blocks and non-opioid analgesics

- Multimodal anesthesia tailored to patient needs

- Immediate postoperative phase

- Daily assessments by the TPS team

- Pain control with minimized opioid use

- Discharge planning with opioid tapering

- Post-discharge follow-up

- Regular phone or in-person follow-ups (weekly to monthly)

- Psychological support sessions (CBT or ACT)

- Adjustments to analgesic plan

- Long-term pain tracking

Best practices and considerations for implementation

Key success factors:

- Institutional support and dedicated personnel

- Clear referral criteria (e.g., opioid tolerance, high pain risk)

- Coordinated care and digital tracking tools

- Virtual delivery options (especially for rural or resource-limited settings)

Barriers:

- Lack of standardized TPS protocols

- Insufficient high-quality evidence

- Cost concerns (though some studies show cost neutrality)

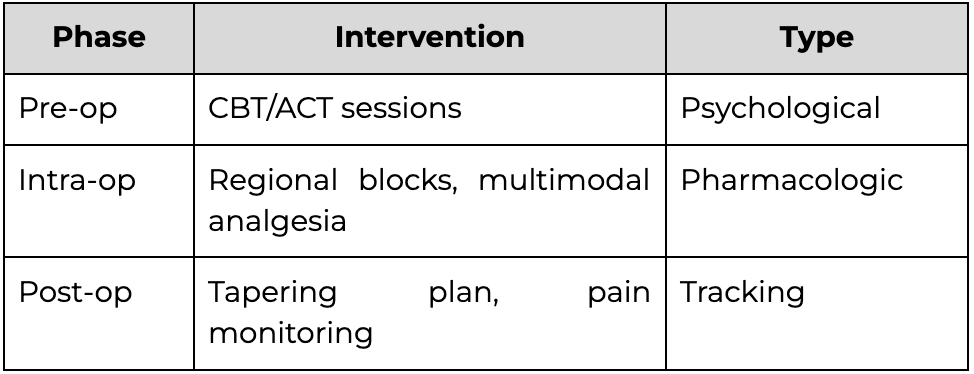

Suggested framework for TPS includes:

Conclusion

Despite promising preliminary outcomes, particularly in opioid reduction, transitional pain services remain under-researched in terms of their ability to prevent chronic postsurgical pain. Nonetheless, their multidisciplinary, patient-centered design positions TPS as a vital evolution in perioperative care, especially for vulnerable populations. Hospitals and pain centers should consider pilot implementations, coupled with data collection, to evaluate the effectiveness of the model and refine it.

Next steps:

- Support ongoing RCTs like the OREOS trial

- Define essential TPS components and implementation standards

- Advocate for policy support and funding

For more information, refer to the full article in Anesthesiology.

Shanthanna H, Khaled M. Transitional Pain Service for Preventing Chronic Postsurgical Pain: A Scoping Review of Published Literature and Considerations for Research and Practice. Anesthesiology. 2025;143(5):1382-1398.

For more information about acute and chronic pain management, get the Ultrasound-Guided Interventional Pain Procedures Manual on NYSORA 360!