In a national cohort of 429,310 children (1–18 years) undergoing noncardiac surgery, preoperative anemia was common (25.7%), and transfusion occurred in 10.4%. Across 2012–2023, both rates stayed flat, but anemia, transfusion, and especially the combination of the two were each associated with higher 30-day mortality and postoperative complications, even after multivariable adjustment.

Why this matters now

Anemia remains the most common pediatric hematologic disorder worldwide, often due to iron deficiency. In the perioperative setting, anemia and allogeneic red blood cell (RBC) transfusion have each been tied to adverse outcomes. This new analysis revisits the question with a large, contemporary US dataset and rigorous risk adjustment, offering a fresh signal for pediatric patient blood management (PBM) programs.

What the study did

- Design: Clinical investigation using the ACS NSQIP-Pediatric databases (2012–2023).

- Population: Children 1–18 years with a recorded preoperative hematocrit (Hct); excluded < 1 year, preop transfusion, congenital heart disease, trauma, solid-organ transplant, and cardiac surgery.

- Anemia definition: Age- and sex-specific Hct thresholds from Nathan and Oski’s Hematology of Infancy and Childhood (e.g., < 33% for 1–2 years, < 38% for males 12–18 years).

- Primary outcomes: 30-day mortality and key postoperative complications (cardiac arrest, unplanned reintubation, pneumonia, septic shock, DVT, reoperation, length of stay).

What stood out from the study

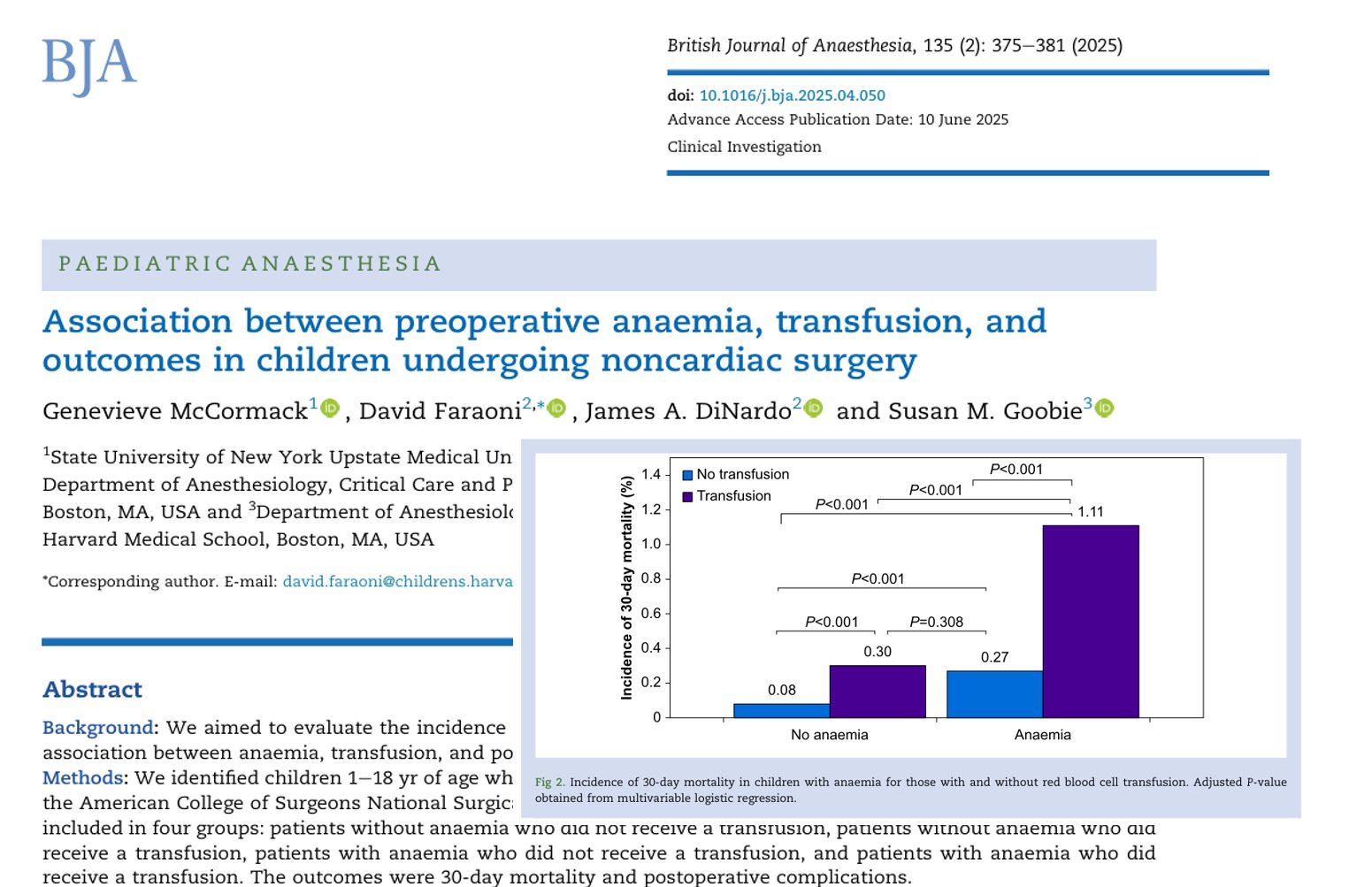

When researchers looked across more than a decade of children’s surgeries, a clear pattern emerged: children who were anemic before surgery, or who needed a blood transfusion around surgery, were more likely to run into trouble afterward. And when both factors came together, anemia plus transfusion, the risks were highest of all.

The team grouped children into four “paths”:

- Healthy blood levels, no transfusion (the best-case scenario).

- Healthy blood levels, but needed a transfusion.

- Anemic before surgery, but no transfusion.

- Anemic and also needed a transfusion (the riskiest group).

Children in the first path usually did very well. Those in the middle two groups, either anemic or needing a transfusion, faced a noticeable uptick in problems like pneumonia, blood clots, and even unexpected trips back to the operating room. But the children in the final path, who had both anemia and transfusion, were the ones most likely to have serious complications or, sadly, not survive within 30 days.

Think of it like layers of risk: anemia adds one layer, transfusion adds another, and together they create a heavier burden for recovery. Even when the researchers adjusted for how sick the children were, how complex their surgeries were, and other factors, this pattern held true.

How to interpret the signal

- Anemia and transfusion are independent risk markers: Each associates with harm, and together they amplify risk. Causality cannot be proven here, but the graded pattern is hard to ignore.

- Case-mix and complexity matter: Children receiving transfusion and/or presenting anemia had higher ASA classes, more comorbidity, more inpatient and emergent care, and longer, more complex operations, factors adjusted for in the models but still important context.

- Practice hasn’t shifted enough: Despite a decade of PBM advocacy, anemia prevalence and transfusion rates are flat across 2012–2023. Implementation gaps likely persist (e.g., limited preop anemia screening, delayed iron therapy).

What counts as preoperative anemia here

Study definitions (Hct thresholds) based on pediatric norms:

- 1–2 years: < 33%

- 2–4 years: < 34%

- 4–7 years: < 35%

- 7–12 years and females 12–18 years: < 36%

- Males 12–18 years: < 38%

These are hematocrit, not hemoglobin, cut-offs, and they align with authoritative pediatric hematology references.

Practical takeaways for perioperative teams

- Screen early: Build routine Hct/Hb screening 3–6 weeks before elective surgery to enable treatment windows.

- Treat iron deficiency first: Prioritise oral or intravenous iron (per local pathways) and address nutritional causes; reserve transfusion for hemodynamic instability, ongoing bleeding, or symptomatic anemia unresponsive to alternatives.

- Optimise conservation: Use antifibrinolytics, meticulous hemostasis, cell-saver where appropriate, and restrictive transfusion thresholds supported by pediatric trials.

- Track and audit: Monitor transfusion triggers, transfusion volumes (ml·kg⁻¹), and outcomes; higher volumes have been linked to more complications in prior work.

Step-by-step: building a pediatric PBM micro-pathway

- Embed screening: At surgical scheduling, auto-order CBC + ferritin ± CRP for children likely to lose blood or with risk factors (recent growth spurts, menstruation, dietary risk, chronic disease).

- Stratify risk: Flag age/sex-adjusted Hct below thresholds; add anemia banner in the perioperative record.

- Treat promptly: Start oral iron (if time allows) or IV iron when surgery is < 3 weeks away or oral therapy is intolerant/ineffective; investigate non-iron causes when indicated.

- Plan the case: Choose techniques that minimise blood loss; consider TXA, tourniquet/controlled hypotension where appropriate; ensure type and screen is ready but avoid default crossmatch for low-risk cases.

- Use restrictive triggers: In stable children without cardiac/neurologic compromise, adhere to restrictive transfusion thresholds from pediatric ICU/surgical trials; escalate based on physiology, not just numbers.

- Dose precisely: If transfusing, calculate ml·kg⁻¹ required to reach a target Hb/Hct, and reassess clinically and with labs; avoid “two-unit” habits.

- Debrief and document: Record indication, trigger, volume, and immediate response; feedback at M&M and quality meetings to tighten practice variation.

Key clinical details at a glance

- Anemia prevalence: 25.7%; stable 2012–2023.

- Transfusion rate: 10.4%; stable over time.

- Highest-risk cell: Anemia + transfusion → aOR ~4 for mortality, 5–7 for major complications (arrest, septic shock).

- LOS gradient: rises from 2 to 5 days across the risk spectrum.

- Complexity and comorbidity: higher in anemic/transfused groups (ASA 3–5, malignancy, respiratory support).

What to watch next

- Prospective pediatric PBM trials testing iron strategies, TXA protocols, and physiology-driven transfusion triggers.

- Implementation science: Can preop anemia clinics in pediatrics move the needle on transfusion exposure and outcomes at scale?

Bottom line

Across 429,310 pediatric noncardiac surgeries from 2012–2023, preoperative anemia and perioperative transfusion, especially together, were independently associated with higher 30-day mortality and complications. The rates of anemia and transfusion haven’t budged in a decade, underscoring a gap between guidelines and practice. The actionable response is clear: screen earlier, treat anemia, conserve blood, and transfuse only when clinically indicated and carefully dosed.

Reference: McCormack G et al. Association between preoperative anaemia, transfusion, and outcomes in children undergoing noncardiac surgery. Br J Anaesth. 2025;135:375–381.

Read more about this topic in the Anesthesia Updates section of the Anesthesia Assistant App. Prefer a physical copy? Get the latest literature and guidelines in book format. For an interactive digital experience, check out the Anesthesia Updates Module on NYSORA360!