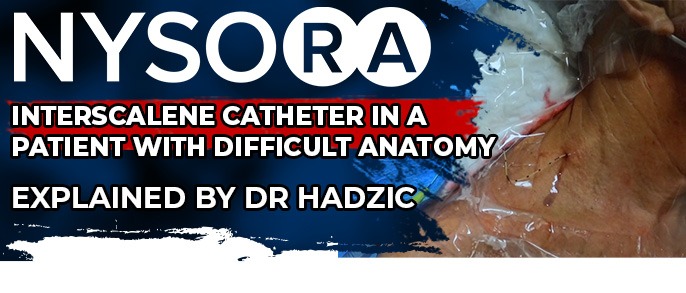

Introduction “Interscalene Catheter In a Patient with Difficult Anatomy”

Insertion of a perineural catheter requires substantially greater expertise than a single-injection block. Moreover, a suboptimal sonoanatomy makes it even more challenging. In this “Interscalene Catheter In a Patient with Difficult Anatomy” teaching video, Dr. Hadzic takes us step-by-step through the decision-making while discussing NYSORA’s pro-tips. What makes this video particularly interesting is that it is filmed real time during clinical teaching where he is guiding one of NYSORA’s fellows to successfully place an interscalene catheter in a patient with challenging anatomy.

Take a note of the 5 standardized steps in catheter placement and the tips on how to prevent catheter misplacement outside of the therapeutic space.

The first brachial plexus blocks were performed by William Stewart Halsted, in 1885, at the Roosevelt Hospital in New York City. In 1902, George Washington Crile described an “open approach” to expose the (axillary) plexus facilitating direct application of cocaine. The need for surgical exposure of the brachial plexus led to limited clinical utility of this technique.

History

This changed in the early 1900s when percutaneous access to the brachial plexus was first described. In 1925, July Etienne1 reported the successful block of the brachial plexus by inserting a needle halfway between the lateral border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle and the anterior border of the trapezius muscle at the level of the cricothyroid membrane, making a single injection in the area around the scalene muscles.

This approach was most likely the first clinically useful interscalene block technique. In 1970, Alon Winnie described the first consistently effective and technically suitable percutaneous approach to the brachial plexus block. The technique involved palpating the interscalene groove at the level of the cricoid cartilage and injecting local anesthetic between the anterior and middle scalene muscles. Winnie’s approach was modified over the years to include slight variations to the technique such as perineural catheter placement. However, the success of this approach and the widespread adoption of the interscalene brachial plexus block as the “unilateral spinal anesthesia for the upper extremity,” should be credited solely to Alon Winnie.

More recently, the introduction of ultrasound-guided techniques has allowed for additional refinements and improved block consistency with reduced local anesthetic volumes.(see Ultrasound-Guided Interscalene Brachial Plexus Block)

Anatomy

The plexus is formed by the ventral rami of the fifth to eighth cervical nerves and the greater part of the ventral ramus of the first thoracic nerve (Figure 1). In addition, small contributions may be made by the fourth cervical and the second thoracic nerves. There are multiple complex interconnections between the neural elements of brachial plexus as they course from the interscalene groove to their endpoints in terminal nerves. However, most of what happens to these roots on their way to becoming peripheral nerves is not clinically essential information for the practitioner.

FIGURE 1. Organization of the brachial plexus.