Lung ultrasound is a standardized domain. Each of its components is based upon pathophysiological realities. As for any novelty, a new terminology had to be considered. The one used in the BLUE-protocol favors fast communication, in the spirit of aviation language: maximal information in minimal time

In this quest, a maximal effort has been done for helping memory. Logic and culture were mixed together. As an example, the term “B-line” should spontaneously suggest interstitial syndrome to any physician. Confusions were avoided for the best. The terms A-lines, B-lines, and up to Z-lines have been chosen on purpose with each time a precise idea helping memorization. We checked that the bat sign, seashore sign, lung sliding, quad sign, sinusoid sign, tissue-like sign, shred sign, lung rockets, stratosphere sign, lung point, BLUE-protocol, etc., did not yield confusion in the medical terminology. The standardization of the method is favored by following seven principles:

- A simple method is suitable for lung ultrasound. A two-dimensional unit without filters or facilities is the most appropriate.

- The thorax is an area where air and water are intimately mingled.

- The lung is the largest organ in the human body.

- All signs arise from the pleural line.

- Lung signs are mainly based on the analysis of the artifacts.

- The lung is a vital organ. Most signs are dynamic.

- Nearly all acute disorders of the thorax come in contact with the surface. This explains the potential of lung ultrasound, which is paradoxical only at first view.

1. DEVELOPMENT OF THE FIRST PRINCIPLE: A SIMPLE METHOD

Two peculiar points highlight lung ultrasound.

First, sophisticated units – usually devoted for cardiac explorations – are not ideal. The large size of these cardiac units, the image resolution, the start-up time, the probe shape, the complexity of the technology, and the high cost can be hindrances for bedside use devoted to critically ill patients The machine that we use, manufactured in 1992, last (cosmetic) update 2008, is perfect for lung – and whole body – analysis. We provide some figures allowing the reader to compare our 1992 resolution with laptop models from the twenty-first century. One figure in particular may explain one of the main reasons of the delay of use of lung ultrasound in many ICUs (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Cardiac probes. This figure shows (right image) how lung ultrasound appeared to many intensivists who had standard echocardiography units. One can understand that they were not fully encouraged to go beyond. Compare with our 1992 machine (left)

Second, the pleural line and the normal signs arising from it (A-lines and lung sliding) are the same at any part of the thorax. The lung is a simple organ, unlike the heart, the abdomen (which contains more than 21 organs), or a fetus.

2. DEVELOPMENT OF THE SECOND PRINCIPLE: UNDERSTANDING THE AIR-FLUID RATIO AND RESPECTING THE SKY- EARTH AXIS

Air and fluids coexist in the lung. Air rises, fluids sink. Lung ultrasound requires precisions on the patient’s position with respect to the sky-earth axis and the area where the probe is applied. Pneumothorax is nondependent, interstitial syndrome usually nondependent, alveolar consolidation usually dependent, and fluid pleural effusion fully dependent.

The critically ill patient can be examined in supine, semirecumbent, or sometimes lateral position, rarely in an armchair, and on occasion in the prone position. Dependent disorders can become nondependent in the prone position.

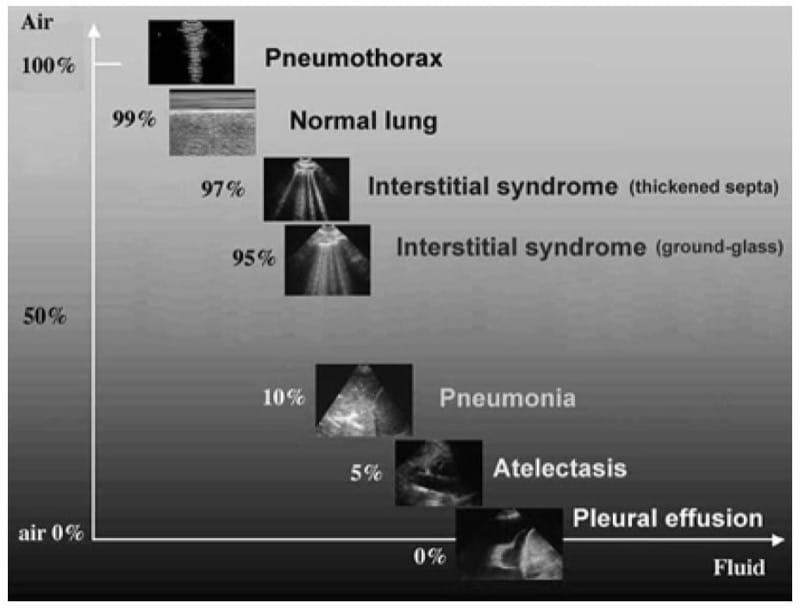

The mingling between air and fluids generates the artifacts because of the high acoustic impedance gradient. Air completely stops the ultrasound beam (acoustic barrier); fluid is an excellent medium that facilitates its transmission. The air-fluid ratio differs completely from one disease to another. We used to describe the disorders from pure fluid to pure air, i.e., pleural effusion (pure fluid), lung consolidation, from atelectasis (mostly fluid) to pneumonia (some air), interstitial syndrome (mostly air), the normal lung (slightly hydrated), and pneumothorax (pure air) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2 The air-fluid ratio curve. The main disorders – and the normal lung – feature between pure air and pure fluid. Note, between pneumothorax and interstitial syndrome, the position of the normal lung. In order not to complicate this graph, we did not feature anaerobic empyema, which contains minute amounts of gas (and has echoic content)

In pleural effusion, the air-fluid ratio is 0.

In lung consolidation, the air-fluid ratio is very low, roughly 0.1 (due to some air bronchograms).

In interstitial syndrome, the air-fluid ratio is very high, roughly 0.95 (air is mingled with minute interstitial edema).

In decompensated COPD or asthma, air is the major component, and the ratio is higher, roughly 0.98.

The normal lung should logically be located here, the air-fluid ratio being roughly the same, 0.98.

In pneumothorax, the air-fluid ratio is 1.

3. THE THIRD PRINCIPLE: LOCATING THE LUNG AND DEFINING AREAS OF INVESTIGATION

This deserves a whole chapter to make sub-headings more visual. The principle is to make a lung ultrasound examination as standardized as an ECG. This principle is linked to the 7th, which defines where the diseases are. Like the ECG, we will define 6 basic points of analysis, three per lung: the BLUE – points.

4. THE FOURTH PRINCIPLE: DEFINING THE PLEURAL LINE

This is the time to take the probe. The pleural line is the basis of lung ultrasound.

5. THE FIFTH PRINCIPLE: DEALING WITH THE ARTIFACT WHICH DEFINES THE NORMAL LUNG, THE A-LINE

This is the time to analyze the resulting image; this is developed in course The A-Profile (Normal Lung Surface): 1) The A-Line .

6. THE SIXTH PRINCIPLE: DEFINING THE DYNAMIC CHARACTERISTIC OF THE NORMAL LUNG, LUNG SLIDING

The lung is a vital organ and therefore moves permanently, from birth to death.

7. DEVELOPMENT OF THE SEVENTH PRINCIPLE: ACUTE DISORDERS HAVE SUPERFICIAL, AND EXTENSIVE, LOCATION

Two providential features make lung ultrasound an accessible discipline:

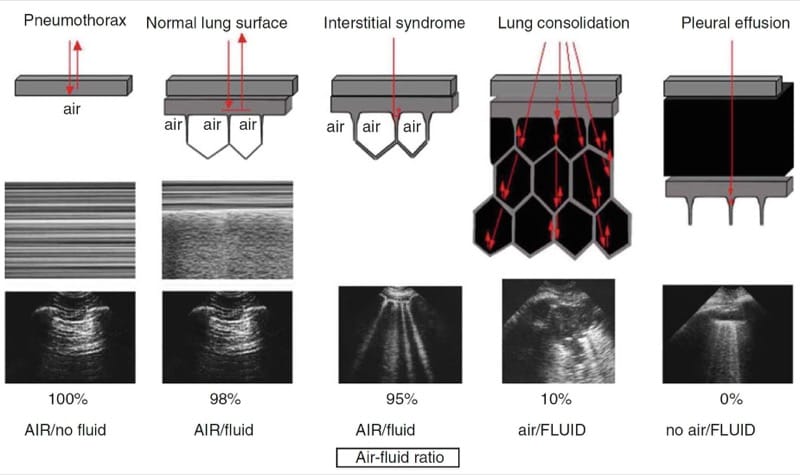

- The lung is a superficial organ. The critical disorders are just near the probe. The superficial extension of most disorders to the pleural line explains the 98–100 % feasibility of lung ultrasound in the critically ill. Pleural effusions and pneumothorax always reach the pleural line (no necessary study for proving it – read any CT). Acute lung consolidations touch the chest wall in nearly all cases. Acute interstitial syndrome extends superficially. The interstitial syndrome detected at the lung surface is a representative sample of deeper interstitial syndrome. Figure 3 explains how these disorders are sharply detected. As opposed to bedside radiography, which creates a summation of pleural, alveolar, and interstitial changes, ultrasound distinguishes each of them. The next chapters will show that each acute disorder gives a particular signal: lung consolidation from pneumonia to atelectasis, interstitial disorders, abscess, even pulmonary embolism, etc.

- The acute lung disorders are usually extensive . Therefore, a few standardized points are sufficient. This property makes LUCI easy, allowing to expedite our fast protocols: time-consuming, chancy scan-nings are unnecessary as opposed to the heart or abdominal organs. Pleural effusions and pneumothoraces develop in a free cavity and, like sheets of paper, have several dimensions. Even if they are “minute,” they are also extensively applied at the wall. Acute interstitial syndrome is in our experience quite always extensive. Lung consolidations make a slight exception, although most cases are located at standardized areas (PLAPS-point). Some can be located anywhere else and be small.

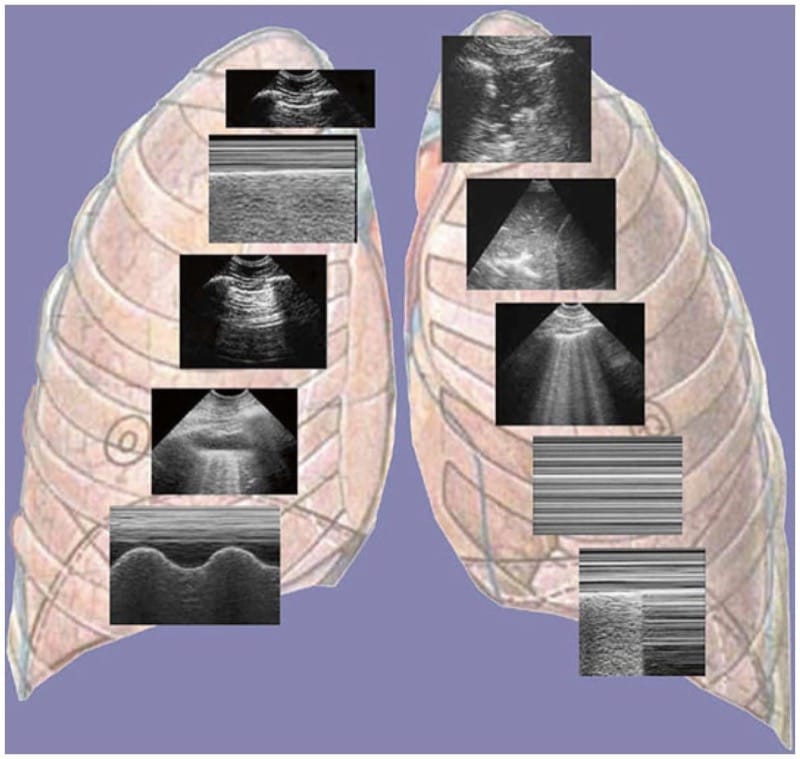

Figure 4 shows that only ten signs are required for diagnosing normal lung surface, pleural effusion, lung consolidation, interstitial syndrome, and pneumothorax.

These are the seven principles of lung ultrasound. Although long described, they received constant improvements aiming at gaining efficiency and simplicity [ 1 ].

Fig. 3 How the main disorders generate specific signs. This figure demonstrates the basis of lung ultrasound according to the air-fluid ratio. Pneumothorax (pure air): the pleural line is drawn only on the parietal pleura. Pure air abuts the pleural line. This yields A-lines. The absence of visceral pleura yields abolition of lung sliding (stratosphere sign). Normal lung surface (99 % air): the dynamics of the visceral pleura generates lung sliding. The normal interlobular septa are too fine for generating B-lines. The visceral pleura contains a layer of cells, with minimal hydric content (sufficient for creating lung sliding). Interstitial edema (95 % air): these subpleural interlobular septa are thickened and surrounded by alveolar gas. The beam penetrates this small mixed system, is trapped after less than one millimeter, and tries to come back at the probe head, but is trapped again, this resulting in persistent to and fro movements, generating one small line at each movement, resulting in a long, vertical looking hyperechoic line, the B-line (an hydroaeric artifact). Although enlarged, the septum is still too small to be directly visualized. Lung consolidation (3 % air): numerous alveoli are filled with fluid (transudate, exudate, etc.). They are separated by (deep) interlobular septa which, thin or thick, generate multiple reflecting interfaces, resulting in a tissue-like pattern. The whole is traversed by the ultrasound beam, resulting in a lump image of lung consolidation. The correct term should therefore be alveolar-interstitial syndrome. There is no place here for the generation of any comettail artifact. Note the irregular end of this (nontranslobar) consolidation, the shred (or fractal) line, which generates the shred or fractal sign. Pleural effusion (pure fluid): the two layers of the pleura are separated by fluid – resulting in a homogeneous pattern (traditionally anechoic, but not for the critical causes: empyema, hemothorax). This image is enclosed by four regular borders, especially the lower one, the lung line, which generates the quad sign.

Fig. 4 The ten basic signs for the lung part of the BLUE-protocol. The first sign, from the left and the top, is the basis (the bat sign). The second and third are signs of normality (A-lines and lung sliding). The rest are pleural effusion (quad sign, sinusoid sign), lung consolidation (shred sign, tissue like sign), interstitial syndrome (lung rockets), and pneumothorax (stratosphere sign and lung point – the A-line sign is already featuring). The only color is the one of the background, for esthetic purpose. No space for Doppler in LUCI. Nice figure indeed (which inspired some manufacturers)