INTRODUCTION

Intensive care specialists play increasingly greater role in the prevention and treatment of physiologic and psychological stress in critically ill patients in order to prevent detrimental consequences ranging from systemic inflammatory response syndrome, to cardiac complications, to posttraumatic stress disorder. Studies have addressed the questions of an optimal sedation regimen, and several evidence-based guidelines and strategies have been published but are frequently not followed. The analgesic component for sufficient stress relief, however, has not been addressed extensively, and few recommendations, primarily based on individual clinical practices, are currently available.

In view of the side effects of opioids, especially respiratory depression, altered mental status, and reduced bowel function, regional analgesia utilizing neuraxial and peripheral nerve blocks offer significant advantages. The lack of a universally reliable pain assessment tool (“analgesiometer”) in the critically ill contributes to the dilemma of adequate analgesia. Many patients in the critical care unit are not able to communicate or use a conventional visual or numeric analog scale to quantify pain. Alternative assessment tools derived from pediatric or geriatric practice that rely on grimacing and other physiologic responses to painful stimuli might be useful but have been inadequately studied in the intensive care unit (ICU). Changes in heart rate and blood pressure in response to nursing activities, dressing changes, or wound care can also serve as indirect measurements of pain, and sedation measures like the Ramsay Sedation Scale or the Riker Sedation-Agitation Scale scale might be helpful although not specifically designed for pain assessment.

The objective of this chapter is to describe the indications, limitations, and practical aspects of continuous regional analgesic techniques in the critically ill based on the available evidence, which at the moment is limited to case reports, cohort studies, expert opinion, and extrapolation from studies looking primarily at the intraoperative use of regional anesthesia extending into the postoperative ICU stay as summarized in a 2012 systematic review in Regional Anesthesia Pain Medicine by Stundner and Memtsoudis who conclude, “Regional anesthesia can be useful in the management of a large variety of conditions and procedures in critically ill patients. Although the attributes of regional anesthetic techniques could feasibly affect outcomes, no conclusive evidence supporting this assumption exists to date, and further research is needed to elucidate this entity.”

EPIDURAL ANALGESIA

Epidural analgesia is probably the most commonly used regional analgesic technique in the ICU setting. Some indications in which epidural analgesia may not improve mortality rates but may facilitate management and improve patient comfort in the ICU include chest trauma, thoracic and abdominal surgery, major vascular surgery, major orthopedic surgery, acute pancreatits, paralytic ileus, cardiac surgery, and intractable angina pain. Although high-risk patients seem to profit most from epidural analgesia, the current literature does not address the specific circumstances of the critically ill patient with multiple comorbidities and organ failure. For that reason, an individual approach is necessary when considering the application of epidural analgesia in this population.

In a survey of 216 general ICUs in England, Low found that 89% of the responding units used epidural analgesia, but only 32% had a written policy governing its use. Although 68% of the responding units would not place an epidural catheter in a patient with positive blood cultures, only 52% considered culture-negative sepsis or systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) to be a contraindication. The majority of respondents did not list lack of consent or the need for anticoagulation after catheter placement as contraindications to the insertion of an epidural catheter. Although the issues of consent, possible coagulopathy, and infection can be addressed rather easily in elective procedures, they become major problems in newly admitted patients; for example, those with multiple trauma or painful intraabdominal processes, especially acute pancreatitis. There is also controversy regarding the safety of placing epidural catheters in sedated patients, and confirmation of a good catheter position can be difficult in the critically ill patient if sensory level testing is not reliable.

Positioning the patient for the procedure may be difficult depending on the underlying injury, the number and position of drains and catheters, and the presence of external fixation devices. Table 1 summarizes the indications, contraindications, and practical problems involved with the placement of epidural catheters.

The help of trained nursing staff is essential for good positioning and safe handling of tubes and catheters during the procedure. Maximum barrier precautions, similar to those used in the placement of central lines, should also be considered when placing epidural catheters in the critically ill. Tunneling the catheter should be considered to prevent dislocation and reduce the risk of catheter site infection. To confirm the correct position of the epidural catheter, electrical stimulation during placement or a postplacement radiograph with a small amount of non-neurotoxic contrast medium may be beneficial. Learn more about Infection Control in Regional Anesthesia.

Bolus injections of long-acting local anesthetics, such as bupivacaine, ropivacaine, or levobupivacaine, or the discontinuation of continuous infusion as needed will allow neurologic assessment when necessary. Monitoring of motor-evoked potentials (MEPs) to the lower extremities and somatosensory-evoked potentials (SSEPs) of the tibial nerve may serve as indicators when the neurologic examination is doubtful due to the patient’s altered mental status. Although routinely used in the operating room for monitoring spinal cord integrity and for the diagnosis and prognosis of spinal cord injury, the use of this technology in the ICU in the context of epidural analgesia has not been adequately assessed.

The most common side effects of epidural blocks are bradycardia and hypotension related to sympathetic block. Hemodynamic changes can be more pronounced with intermittent bolus dosing, in patients with hypovolemia, and in those with reduced venous return secondary to high positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) ventilation.

TABLE 1. Epidural analgesia in the Critically Ill.

| Indications | Contraindications | Practical Problems | Dose Suggestions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thoracic epidurals: | |||

| Chest trauma | Coagulopathy or current use of anticoagulants during catheter placement and removal61,62 | Positioning of patient | Bolus regimen: |

| Thoracic surgery | Monitoring of neurologic function (consider MEP/SSEP) | 5–10 mL 0.125–0.25% bupivacaine or 0.1–0.2% ropivacaine q 8–12 h |

|

| Abdominal surgery | |||

| Paralytic ileus | Consider addition of 1–2 meg clonidine in hemodynamically stable patients |

||

| Pancreatitis | Sepsis/bacteremia | ||

| Intractable angina | Local infection at puncture site | ||

| Lumbar epidurals: | |||

| Orthopedic surgery or trauma of lower extremities | Severe hypovolemia | Continuous infusion: | |

| Acute hemodynamic instability | 0.0625% bupivacaine or 0.1% ropivacaine at 5 mL/h |

||

| Peripheral vascular disease of lower extremities | Obstructive ileus | Consider addition of opioids (eg, hydromorphone, sufentanil) or clonidine if high systemic opioid demands persist |

Based on data from lumbar punctures and meningitis from the beginning of the twentieth century, current sepsis and bacteremia are considered contraindications for intrathecal opioid applications and, by analogy, for the placement of an epidural catheter. However, many ICU patients, especially after trauma or major surgery, present with a clinical picture of SIRS. Fever and increased white blood cell count alone, that is, in the absence of positive blood cultures, do not provide a reliable diagnosis of bacteremia.

The combination of the serum markers C-reactive protein (CRP), procalcitonin, and interleukin-6, on the other hand, have been shown to indicate bacterial sepsis with a high degree of sensitivity and specificity and can guide the decision to place an epidural catheter. Regarding the patient’s coagulation status, the current recommendations of the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine (ASRA) should be followed. Adequate safety intervals during the administration of anticoagulant drugs are equally important for the placement and removal of epidural catheters. Although there is no compelling evidence of an increased risk of epidural bleeding with developing coagulopathy or therapeutic anticoagulation while an epidural catheter is in place, the benefits of epidural analgesia should be weighed against this potential, highly detrimental complication. This risk might lead to increased utilization of paravertebral blocks, as described in a U.K. survey of elective thoracic surgery. However, Luvet and colleagues have described a high misplacement rate of paravertebral catheters using the landmark technique and a discrepancy between contrast medium spread and loss of sensation, which makes an assessment of the effectiveness of this technique in the sedated critically ill patient very difficult.

In a small cohort study of 153 thoracic and 4 lumbar epidurals in critically ill patients, we could not identify an increased complication risk compared to the reference databank. However, the duration of catheter use was significantly longer (mean 5 days, range 1–21 days) in the critically ill group.

NYSORA Tips

- The most common side effects of epidural blocks are bradycardia and hypotension related to sympathetic block.

- Hemodynamic changes can be more pronounced with intermittent bolus dosing, in patients with hypovolemia, or in patients with reduced venous return secondary to high positive end-expiratory pressure ventilation.

- Discontinuation of continuous infusion allows neurologic assessment when necessary.

- There is no hard evidence that there is increased risks of epidural bleeding with developing coagulopathy or therapeutic anticoagulation while an epidural catheter is in place. Nevertheless, the benefits of epidural analgesia should be weighed against the risk of this serious complication.

PERIPHERAL NERVE BLOCKS FOR THE UPPER EXTREMITIES

There are currently no randomized, controlled trials or large prospective trials evaluating the use of peripheral nerve blocks for the upper extremity in critically ill patients. Nevertheless, severe trauma to the shoulder or arm is often part of multiple injuries due to traffic or workplace accidents, often in combination with blunt chest trauma requiring mechanical ventilation. These injuries can contribute to severe pain, especially during positioning of the patient. If the orthopedic injury is part of complex trauma including brain injury in which the mental status of the patient is altered and opioid-based analgesic regimens might mask the neurologic situation, sufficient analgesia can be achieved for the shoulder or upper limb with either continuous interscalene, continuous cervical paravertebral, or infraclavicular approaches to the brachial plexus.

Particular concerns arise concerning the placement of regional blocks in ICU patients with impaired mental status due to neurologic injury or therapeutic sedation. Benumof reported a small series of serious complications, including spinal cord injury related to the interscalene approach, which may have been associated with sedation or general anesthesia. His case descriptions relate to spinal cord injury in heavily sedated or anesthetized patients and not to the injury of the peripheral nerves. Despite this, the performance of blocks anatomically close to the neuraxis can indeed carry a higher risk of spinal cord needle or injection injury. In sedated critically ill patients, a combination of ultrasound and nerve stimulation for the placement of interscalene catheters and a technique with a less medial needle direction should help to minimize the risk of complications.

Perhaps most importantly, such blocks should be performed only by clinicians with adequate experience. The unavoidable blocking of the phrenic nerve and the loss of hemi-diaphragmatic function should be considered while planning the intervention. Although phrenic nerve block has negligible effects in mechanically ventilated patients, it may impair weaning from mechanical ventilation in high-risk patients. Furthermore, the proximity of the insertion site of the interscalene catheter to a tracheostomy tube might increase the risk of infection, and careful, standardized monitoring of the puncture site is therefore needed. Positioning problems might limit the use of the cervical paravertebral approach, which provides good analgesia for the shoulder, arm, and hand.

The continuous infraclavicular and axillary approaches provide good analgesia for most of the arm, elbow, and hand. A bolus injection of local anesthetic through the catheter should be considered especially in patients who need surgical anesthesia for procedures such as painful dressing changes or debridements for burns or large soft tissue wounds in the affected area. A lateral infraclavicular approach avoids the pneumothorax and allows better securing of the catheter, compared to more proximal approaches to brachial plexus block where the catheter is placed more superficially and the soft tissue is more movable.

NYSORA Tips

- In patients with altered mental status in whom opioid-based analgesic regimens might make neurologic evaluation difficult, excellent analgesia can be achieved for the shoulder or upper limb with continuous interscalene, cervical paravertebral, or infraclavicular approaches to the brachial plexus.

- Performance of blocks anatomically close to the centroneuraxis can carry a higher risk of spinal cord needle or injection injury. In heavily sedated critically ill patients, such blocks should be performed only by clinicians with adequate experience.

- An interscalene brachial plexus block results in the loss of hemi-diaphragmatic function. Although phrenic nerve block has negligible effects in mechanically ventilated patients, it may impair weaning from mechanical ventilation in high-risk patients.

- Real-time ultrasound guidance for peripheral catheter placement

PERIPHERAL NERVE BLOCKS FOR THE LOWER EXTREMITIES

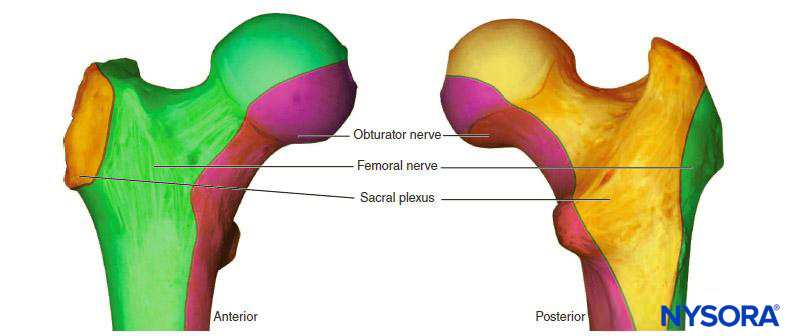

Femoral nerve catheters are helpful in the management of acute pain from femoral neck fractures in the period between injury to shortly after surgical stabilization of the fracture. Skilled use of ultrasound might limit the unavoidable pain associated with nerve stimulation in this situation, which otherwise can be treated with small doses of intravenous remifentanil (0.3–0.5 mcg/kg) or ketamine (0.2–0.4 mg/kg). A fascia iliaca compartment block might be a technical alternative.

A continuous femoral catheter in combination with a sciatic block provides excellent pain relief for the whole leg and even surgical anesthesia for procedures like external fixation. Whether an anterior or posterior approach (midgluteal or subgluteal classical Labat approach with one or two injections) to the sciatic nerve is chosen depends largely on the skills of the operator and the ability to adequately position the patient for the procedure.

If a combination of catheter techniques is used, as is often needed for the lower extremity, the total daily dose of local anesthetic should be adjusted based on catheter location, admixtures like epinephrine, drug interactions, and disease states as summarized in a recent review by Rosenberg and coworkers. A bolus injection of long-lasting local anesthetics in combination with clonidine or buprenorphine may help to reduce the overall amount of local anesthetic needed and minimize the effects of local anesthetic toxicity, although research results on these adjuvants are equivocal at present.

OTHER REGIONAL ANALGESIC TECHNIQUES

Celiac plexus blocks may provide excellent analgesia for pancreatitis and cancer-related upper abdominal pain, but technical difficulties in the critically ill (computed tomography [CT] guidance, fluoroscopy, or transgastric ultrasound) and the need for repeated injections limit their value for acutely critically ill patients.

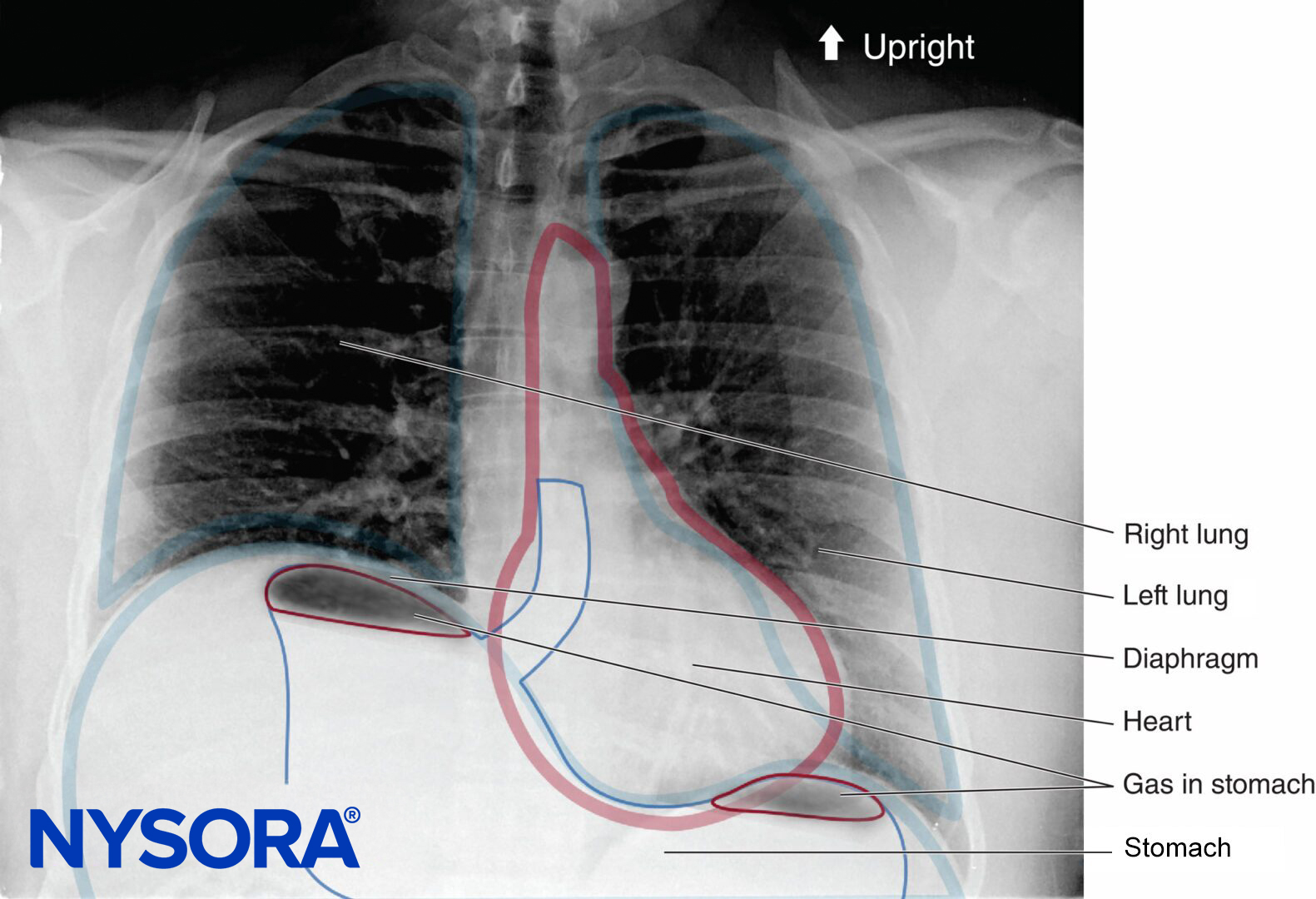

Intrapleural catheters for pain control after chest trauma are of limited value secondary to concurrent drainage from chest tubes. The risk of pneumothorax limits their benefits for the management of pain after conventional cholecystectomy compared with the epidural or paravertebral technique in ventilated patients. Thoracic paravertebral catheters can be a valuable alternative to epidural catheters for the management of unilateral pain restricted to a few dermatomes (eg, rib fractures or zoster neuralgia). Table 2 provides a summary of the most utilized continuous peripheral catheters.

Single-injection nerve blocks (eg, intercostal blocks for the placement of chest tubes), scalp blocks for the placement of halo fixation, and sufficient local infiltration anesthesia for typical ICU procedures (eg, placement of arterial and central venous catheters, lumbar punctures, and ventriculostomies) are often forgotten, although they are easy and safe to perform. If EMLA cream is used for topical anesthesia, it needs to be applied 30–45 minutes before the procedure to achieve optimal effect. Intrathecal morphine injections as a single shot or via spinal catheter (microcatheters are currently not approved in the United States but are available in Europe) can be an alternative to epidural catheters, especially if only short-term use after surgery is anticipated.

SYSTEMIC EFFECTS & COMPLICATIONS OF LOCAL ANESTHETICS IN THE CRITICALLY ILL PATIENT

Local anesthetics have been shown to have several positive systemic effects (including analgesic, bronchodilatory, neuroprotective, anti-inflammatory, antiarrhythmic, and antithrombotic properties) when given or absorbed in adequate quantities (the exact dose-response relationships are widely unknown).

They also have negative effects, such as neurotoxicity (dose-dependent), myotoxicity, inhibition of wound healing, cardiotoxicity (dose-dependent), and central nervous excitation or depression (dose dependent). To prevent local anesthetic systemic toxicity from accidental intravascular injection, a test dose of local anesthetic or saline with 1:200,000 epinephrine can be used with catheter placement, but the sensitivity of heart rate, blood pressure increase, and T-wave changes might be altered in ICU patients, especially those treated with beta-block and α2-agonists or catecholamines.

Careful aspiration to check for blood return should be performed before each bolus injection. Most studies examining plasma levels of local anesthetics were not performed in critically ill patients. Scott and colleagues described the safe use of epidural ropivacaine 0.2% for 72 hours wi žth plasma levels far below the toxic threshold, and Gottschalk and associates observed safe plasma levels after 96 hours in patients treated with thoracic epidural ropivacaine 0.375%, indicating no significant accumulation over time. A lipid resuscitation protocol should be in place and part of the regular resuscitation drills in the ICU, where practitioners are often not as familiar with this topic as are operating room (OR) anesthesiologists but have easy access to the required quantities of lipid emulsion.

TABLE 2. Continuous peripheral nerve blocks in the critically Ill.

| Block | Indications | Contraindications | Practical Problems | Dose Suggestions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interscalene | Shoulder/arm pain | Untreated contralateral pneumothorax | Horner syndrome may obscure neurologic assessment | Bolus regimen:a |

| 10 mL 0.25% bupivacaine or 0.2% ropivacaine q 8–12 h and on demand | ||||

| Dependence on diaphragmatic breathing | Block of ipsilateral phrenic nerve | |||

| Contralateral vocal cord palsy | Close proximity to tracheostomy and jugular vein line sites | Continuous infusion: | ||

| 0.125% bupivacaine or 0.1–0.2% ropivacaine at 5 mL/h | ||||

| Local infection at puncture site | ||||

| Cervical paravertebral | Shoulder/elbow/wrist pain | Severe coagulopathy | Horner syndrome may obscure neurologic assessment | Bolus regimen:a |

| Dependence on diaphragmatic breathing | 10 mL 0.25% bupivacaine or 0.2% ropivacaine q 8–12 h and on demand | |||

| Contralateral vocal cord palsy | Block of ipsilateral phrenic nerve | Continuous infusion: | ||

| Local infection at puncture site | Patient positioning | 0.125% bupivacaine or 0.1–0.2% ropivacaine at 5 mL/h | ||

| Infraclavicular | Arm/hand pain | Severe coagulopathy | Pneumothorax risk | Bolus regimen:a |

| Untreated contralateral pneumothorax | Steep angle for catheter placement | 10–20 mL 0.25% bupivacaine or 0.2% ropivacaine q 8–12 h and on demand | ||

| Local infection at puncture site | Interference with subclavian lines | Continuous infusion: | ||

| 0.125% bupivacaine or 0.1–0.2% ropivacaine at 5–10 mL/h | ||||

| Axillary | Arm/hand pain | Local infection at puncture site | Arm positioning | Bolus regimen:a |

| Catheter maintenance | 10–20 mL 0.25% bupivacaine or 0.2% ropivacaine q 8–12 h and on demand | |||

| Continuous infusion: | ||||

| 0.125% bupivacaine or 0.1–0.2% ropivacaine at 5–10 mL/h | ||||

| Paravertebral Thoracic Lumbar | Unilateral chest or abdominal pain restricted to few dermatomes | Severe coagulopathy | Patient positioning | Bolus regimen:a |

| Untreated contralateral pneumothorax | Stimulation success sometimes hard to visualize | 10–20 mL 0.25% bupivacaine or 0.2% ropivacaine q 8–12 h and on demand |

||

| Local infection at puncture site | ||||

| Continuous infusion: | ||||

| 0.125% bupivacaine or 0.1–0.2% ropivacaine at 5–10 mL/h |

||||

| Femoral or sciatic | Unilateral leg pain | Severe coagulopathy | Patient positioning | Bolus regimen:a |

| Local infection at puncture site | Interference of femoral nerve catheters with femoral lines | 10 mL 0.25% bupivacaine or 0.2% ropivacaine q 8–12 h and on demand |

||

| Continuous infusion: | ||||

| 0.125% bupivacaine or 0.1–0.2% ropivacaine at 5 mL/h |

GENERAL MANAGEMENT ASPECTS OF CONTINUOUS REGIONAL ANALGESIA CATHETERS IN CRITICALLY ILL PATIENTS

In general, given the lack of cooperation and communication in many ICU patients, regional analgesia techniques using continuous catheters in the ICU require a higher level of vigilance than needed for regular ward patients. Close cooperation between the ICU team and the acute pain or anesthesia service of the hospital is required.

Critical care nursing personnel should be specifically trained in handling regional analgesia catheters and must be aware of the potential complications and their early warning signs. Because of the frequently large and confusing numbers of various infusion catheters in critically ill patients, the risk of drug errors and incorrect administration of drugs through continuous regional analgesia catheters may be higher in these patients. Well-trained and highly qualified personnel are the best safeguard against these complications aside from eye-catching labels, standardized care protocols, and perhaps specially designed connectors for those catheters.

Comprehensive diagnostic approaches, including magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or CT, should be undertaken when there are clinical signs of possible bleeding complications (eg, suspected epidural or retroperitoneal hematoma). Structured observations of catheters for infectious complications and careful adherence to aseptic technique during catheter placement and tunneling, as well as the possible use of antibiotic-coated catheters in the future, may reduce possible infectious complications.

Catheters should not be removed routinely after certain time intervals but only when clinical signs of infection appear. A study by Langevin suggests that if catheters become disconnected when the fluid in the catheter is static, the proximal 25 centimeters of the catheter may be immersed in a disinfectant, cut, and reconnected to a sterile connector. This technique is feasible only for catheters in which the fluid column can be observed. Stimulating catheters should never be cut because of the danger of unwinding the internal metal spiral wire, which conducts electrical current. No study has examined the risk of reconnecting these catheters after thorough disinfection of the outer surface, which is likely a common practice in many institutions. Cuvillon and colleagues reported a high overall incidence of colonization (57%) of femoral catheters without septic complications. Therefore, the decision to reconnect or remove the catheter must be made on a case-by-case basis and based on the specific clinical circumstances. The overall risk of permanent neurologic damage (from direct trauma, bleeding, or serious infection) or death from regional anesthesia and analgesia seems to be low in the perioperative setting, as shown by large surveys by Auroy and coworkers and Moen and associates. Although both studies certainly include critically ill patients, there are no specific subgroup data available.

If the patient is cooperative enough, patient-controlled regional anesthesia (PCRA) regimen is preferable, and such systems can also be used in a nurse-controlled fashion for intermittent bolus application without the need for additional manipulation of the infusion system.

While the evidence for the overall improvement of patient safety using ultrasound-guided regional anesthesia (UGRA) placement techniques is limited and a certain level of training necessary, the use of ultrasound seems to be especially beneficial in the critically ill patient. In a semiquantitative review, Morin and coworkers demonstrated better analgesia with the use of stimulating catheters, which seem to be another instrument to improve the effectiveness of regional analgesia in the critically ill. Read more about Continuous Peripheral Nerve Blocks: Local Anesthetic Solutions and Infusion Strategies.

The complexity of individual clinical situations can be demonstrated by the following case example: A 55-year-old male patient with polycythemia vera, treated with periodic phlebotomy and a history of lower extremity DVTs [deep venous thromboses], was admitted to the hospital with acute ischemia of all 5 fingers of his right hand. His INR [international normalized ratio] on admission was 2.5. His fingers were cold and painful and showed bluish discoloration. The patient was evaluated by vascular surgeons and an angiogram showed arterial thrombosis of the right hand and rtPA [recombinant tissue plasminogen activator] thrombolysis was started by an indwelling catheter from the right femoral artery to the right subclavian artery. The patient was admitted to the Surgical Intensive Care Unit for monitoring during TPA [tissue plasminogen activator]-thrombolysis.

Overnight, no significant improvement in limb perfusion could be seen and the patient underwent re-angiography on postoperative day 1. Given the amount of residual thrombosis, rtPA-treatment was continued. Overnight, on postoperative day 1, the patient became disoriented after receiving a single dose of meperidine in addition to his morphine PCA [patient-controlled analgesia] for worsening pain in his arm. A CT scan performed at that time to exclude an acute bleeding complication was read as normal and his neurologic status returned to baseline. rtPA treatment was discontinued after 48 hours on postoperative day 2, and the catheter was removed. A heparin infusion was titrated to a PTT [partial thromboplastin time] around 70 seconds. Around midnight the patient became agitated and disoriented.

Another head CT was performed which showed left cerebellum hypodensity and the patient became more and more unresponsive. Brain MRI revealed multiple infarcts involving the left cerebellum, the right cerebellum, the bilateral thalami and the left medial temporal occipital region. MRA [magnetic resonance angiogram] showed left vertebral artery thrombosis. The patient was treated symptomatically with small doses of haloperidol and the heparin infusion was discontinued by the neurologist’s recommendation to prevent hemorrhagic transformation of the cerebellar infarcts. In the morning, the patient was still somnolent but complained about severe pain in his right arm when aroused. Also, the discoloration of his fingers was slowly progressing proximally and the distal parts were cold and numb. The patient also described a burning sensation in addition to the sharp and shooting pain. Morphine PCA and systemic narcotics had been discontinued secondary to his worsened neurostatus. 18 hours after discontinuation of rtPA and 9 hours after discontinuation of the heparin infusion his fibrinogen levels were still markedly elevated but his INR and PTT had returned to high normal values.

An axillary brachial plexus catheter was placed using the stimulating catheter (Stimucath®, Arrow International, Reading, USA) and a good motor response with hand extension and thumb adduction at 0.44 mA was elicited via the indwelling catheter after ultrasound guided advancement of the catheter. A bolus of 20 mL of mepivacaine 1.5 percent and 20 mL of ropivacaine 0.75 percent were injected through the catheter and resulted in pain relief after 10 minutes. The skin temperature in the affected hand rose from 34.5 degrees Celsius to 36 degrees Celsius 30 minutes after injection of the local anesthetic. Ultrasound guidance was used for the placement of the axillary catheter to avoid accidental puncture of the axillary artery or vein 4. The catheter was tunneled to prevent dislocation and there was mild oozing at the tunnel site but no hematoma formation. A cerebral angiogram was performed and showed left vertebral artery thrombosis and a patent right vertebral artery.

Lower extremity duplex sonography showed extensive subacute deep venous thrombosis bilaterally and an inferior vena cava filter was placed. Transthoracic echo and transesophageal echo showed a small PFO [patent foramen ovale] with minimal right to left shunt with Valsalva maneuver. The axillary catheter was bolused with 10 mL of 0.5 percent ropivacaine every 8 hours. This regimen allowed consistent pain relief and sympathetic block. Finger cyanosis was improving rapidly. With improved neurostatus, the patient was also started on gabapentin 900 mg every 8 hours, 325 mg of aspirin and codeine tablets PRN. The hematologist recommended enoxaparin 100 mg sc q 12 hours for the treatment of his hypercoagulable state. The axillary catheter was removed after 5 days immediately before his evening dose of enoxaparin. No bleeding complications were observed. His neurological status as well as the finger ischemia continued to improve.

SUMMARY

Regional analgesia, whether utilizing single-injection regional blocks or continuous neuraxial or peripheral catheters, can play a valuable role in a multimodal approach to pain management in the critically ill patient to achieve optimum patient comfort and to reduce physiologic and psychological stress. By avoiding high systemic doses of opioids, several complications, such as withdrawal syndrome, delirium, mental status changes, and gastrointestinal dysfunction, can be reduced or minimized. Because of the limited patient cooperation that is common during the placement and monitoring of continuous regional analgesia in the critically ill, indications for its use must be carefully based on anatomy, clinical features of pain, coagulation status, and logistic circumstances.

Highly trained nursing personnel and well-trained physicians are essential prerequisites for the safe use of these techniques in the critical care environment. These recommendations are based on small series, uncontrolled trials, and extrapolations from controlled trials in the perioperative setting; further research on the use of regional analgesia techniques in the critically ill is needed before definitive guidelines can be established.

Clinical updates

Katz et al. (Current Pain and Headache Reports, 2025) summarize emerging evidence that regional anesthesia in the ICU reduces opioid exposure, ventilator duration, delirium, and ICU length of stay after cardiac, thoracic, and major abdominal surgery. While thoracic epidural analgesia remains effective, the review highlights growing preference for truncal fascial plane blocks (ESPB, SAP, PECS, TAP, QL) due to fewer hypotensive and bleeding complications in critically ill patients. The authors note that evidence is largely extrapolated from perioperative studies, underscoring the need for ICU-specific trials to define optimal techniques and outcomes.

Campbell et al. (Current Opinion in Anaesthesiology, 2024) report expanding indications for regional anesthesia in critical care beyond analgesia, including management of ventricular storm and cerebral vasospasm. Advances in ultrasound guidance and superficial fascial plane techniques have improved safety and feasibility, enabling reductions in opioid use, mechanical ventilation time, ICU length of stay, and possibly mortality. The authors argue that despite persistent barriers (training, resources, patient complexity), regional anesthesia should be more routinely integrated into ICU pain and physiologic management pathways.

Ott et al. (Journal of Clinical Medicine, 2024) review non-neuraxial chest and abdominal wall regional anesthesia in ICU patients and conclude that ultrasound-guided fascial plane blocks (ESPB, SAPB, PECS, TAP, QL) offer effective opioid-sparing analgesia with more favorable hemodynamic and anticoagulation profiles than neuraxial techniques. The authors emphasize that altered pharmacokinetics, sedation that masks neurologic symptoms, and increased LAST risk in critical illness mandate dose reduction, ultrasound guidance, and heightened cardiac monitoring. Overall, they support broader ICU adoption of peripheral and fascial plane blocks as practical, safer complements to opioid-based regimens, particularly for rib fractures, thoracic surgery, and abdominal pathology.