1. INTRODUCTION

Although the soft tissue anatomy of the forearm is complex due to the high number of muscles involved in the spectrum of wrist and fingers movements, musculoskeletal pathology amenable to US examination is relatively uncommon in this area. Only a few specific conditions affecting the median nerve proximal to the carpal tunnel level merit separate consideration.

2. CLINICAL AND US ANATOMY

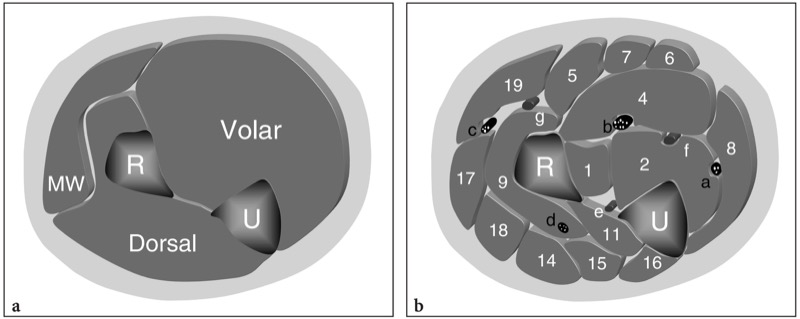

Strong septal attachments of the antebrachial fascia to the radius, the ulna and the interosseous membrane divide the forearm into three distinct compartments – volar, dorsal and the so-called mobile wad – each of which house several muscles (Fig. 1). The volar compartment (flexor compartment) contains eight muscles – the flexor pollicis longus, the flexor digitorum profundus, the flexor digitorum superficialis, the pronator teres, the palmaris longus, the flexor carpi radialis, the flexor carpi ulnaris and the pronator quadratus – and the most relevant neurovascular structures of the limb, including the median nerve along with its main divisional branch, the anterior interosseous nerve, the ulnar nerve and the ulnar artery. The dorsal compartment (extensor compartment) houses eight muscles: the supinator, the extensor pollicis brevis, the abductor pollicis longus, the extensor pollicis longus, the extensor indicis proprius, the extensor digitorum communis, the extensor digiti minimi and the extensor carpi ulnaris. At the radial aspect of the forearm, three other muscles – the extensor carpi radialis brevis and longus (extensors) and the brachioradialis (flexor) – form the so-called mobile wad. The superficial sensory branch of the radial nerve and the radial artery run between the mobile wad compartment and the volar compartment of the forearm. A basic review of the compartmental normal and US anatomy of the forearm with a description of the courses of the radial, median and ulnar nerves is included here.

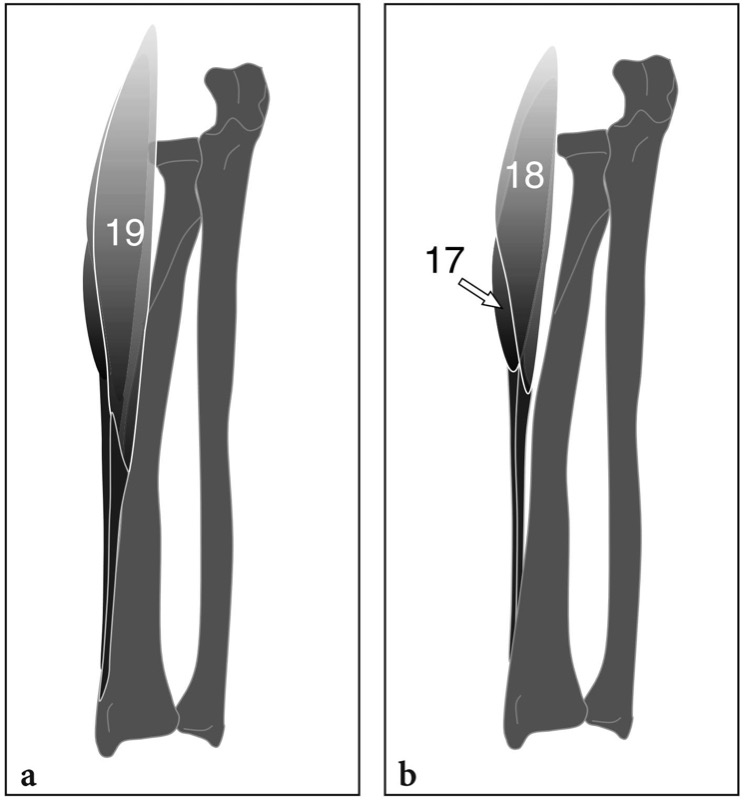

Fig. 1 a,b. a Schematic drawing of a transverse view through the right forearm showing the relationships of the volar (flexor) and dorsal (extensor) compartments and the mobile wad (MW) with the radius (R) and ulna (U). b The position of the individual muscles (see a for reference) is illustrated for each compartment. The volar compartment consists of deep and superficial layers of muscles. In the deep layer, the flexor pollicis longus (1) and the flexor digitorum profundus (2) lie superficial to the bones and the interosseous membrane and deep to the ulnar (a) and median (b) nerves. The superficial layer of the volar muscles includes the fl exor digitorum superficialis (4), the pronator teres (5), the palmaris longus (6), the flexor carpi radialis (7) and the flexor carpi ulnaris (8). The dorsal compartment is smaller than the volar one and houses the supinator (9) and the abductor pollicis longus (11) which lies in a deep position, and the more superficial extensor digitorum longus (14), extensor digiti minimi (15), extensor carpi ulnaris (16). The mobile wad includes the extensor carpi radialis longus (17), extensor carpi radialis brevis (18) and brachioradialis (19). The superficial branch (c) of the radial nerve runs between the dorsal compartment and the mobile wad, whereas the posterior interosseous nerve (d) courses more posteriorly, inside the supinator muscle. Note the position of the radial artery (g), the ulnar artery (f) and the anterior interosseous artery (e) relative to the adjacent muscles and nerves.

3. VOLAR FOREARM

The volar (anterior) compartment of the forearm includes the flexor and pronator (antebrachial) muscles. It can be divided by a transverse septum into two layers: deep and superficial (Boles et al. 1999).

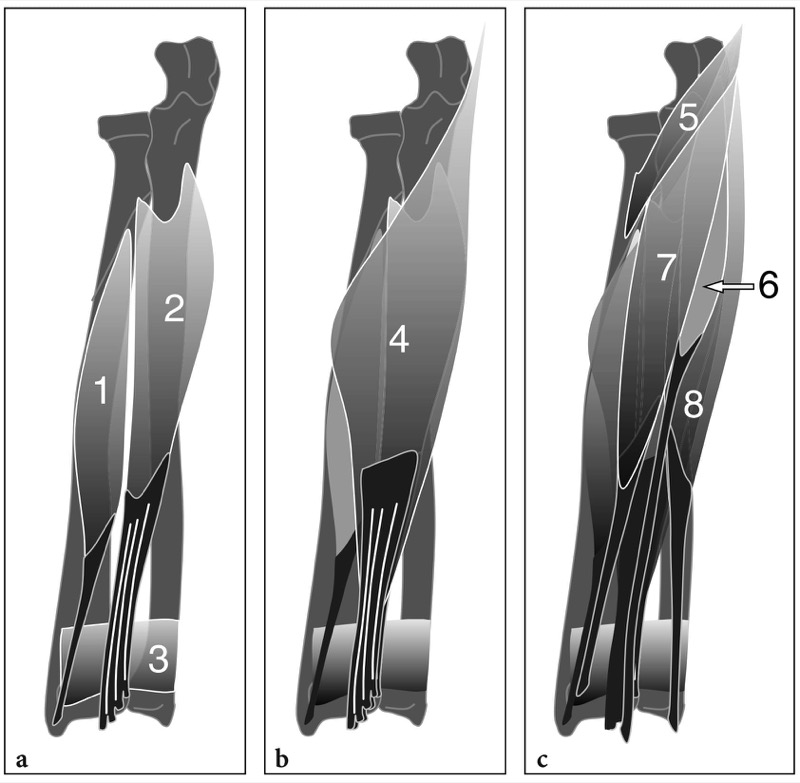

The deep layer of muscles contains the flexor pollicis longus, the flexor digitorum profundus and the pronator quadratus (Fig. 2a). The flexor pollicis longus takes its origin from the anterior radius and the interosseous membrane and continues down in a distal tendon which passes deep to the flexor retinaculum. Medial to it, the flexor digitorum profundus has a more extensive origin from the ulna and the interosseous membrane. Distally, it divides into four slips which pass deep to the tendons of the flexor digitorum superficialis to reach the fingers. These two muscles insert into the distal phalanx of the thumb (flexor pollicis longus) and the second through fifth fingers (flexor digitorum profundus). The pronator quadratus muscle is the deepest of the volar muscles and the only one that arises from the ulna and inserts into the radius.

The superficial layer of volar muscles consists of the flexor digitorum superficialis, the pronator teres, the palmaris longus, the flexor carpi radialis and the flexor carpi ulnaris (Fig. 2b,c). These muscles take their origin from a strong common tendon which arises from the medial epicondyle. The flexor digitorum superficialis, the largest muscle of the superficial layer, consists of three heads – humeral, ulnar and radial – which join at the proximal forearm and continue distally in four distal tendons that insert into the middle phalanx of the second through the fifth finger. This muscle lies just superficial to the flexor digitorum profundus. The pronator teres is a short muscle which originates from two proximal heads: a larger humeral, attached to the medial epicondyle, and a smaller ulnar attached to the coronoid process. Both pass obliquely across the forearm to attach into the middle third of the medial surface of the radius. The palmaris longus is a small fusiform muscle which is absent on one or both sides in approximately 12% of individuals (Reimann et al. 1944): its belly is located between the medial flexor digitorum superficialis and the lateral flexor carpi radialis. At the proximal forearm, this muscle continues into a long, slender and very superficial tendon that attaches into the transverse carpal ligament. The flexor carpi radialis and the flexor carpi ulnaris arise at the medial epicondyle from the common flexor tendon origin and descend the anterior compartment of the forearm in a lateral (flexor carpi radialis) and medial (flexor carpi ulnaris) position (Fig. 2b): they continue into two long tendons which respectively insert into the second metacarpal and the pisiform. From the biomechanical point of view, the flexor digitorum superficialis flexes the proximal interphalangeal joint of the fingers, the pronator teres pronates the forearm and aids in elbow flexion, and the three more superficial muscles (palmaris longus, flexor carpi radialis and flexor carpi ulnaris) flex the wrist.

Fig. 2a–c. Schematic drawings of a coronal view of the muscles of the volar compartment of the forearm from deep (a) to superficial (c). a The deep layer includes the flexor pollicis longus (1) and the flexor digitorum profundus (2), which have a wide origin from the interosseous membrane, the radius and the ulna. Their distal tendons pass superficial to the pronator quadratus (3) before entering the carpal tunnel. b Superficial to these muscles, the flexor digitorum superficialis (4) is a broad muscle which arises from the humerus, the ulna and the radius. Its distal tendons are disposed in series over those of the flexor digitorum profundus. c Over the fl exor digitorum superficialis, the pronator teres (5), the palmaris longus (6), the flexor carpi radialis (7) and the flexor carpi ulnaris (8) originate from the medial epicondyle. While the pronator teres traverses the proximal forearm obliquely to insert into the radius, the other superficial muscles lie adjacent one to the other and descend the forearm to continue in long distal tendons down to the wrist

Some anomalous muscles may be encountered in the forearm, the two more common of which are the anomalous palmaris and the Gantzer muscle. The palmaris longus is one of the most variable muscles in the human body, with an overall incidence of anomalies of 9% (Reimann et al. 1944). Occasionally, its muscle belly can be found in a central position between discrete proximal and distal tendons (digastric variant), or even distally. When located distally, the muscle has a long proximal tendon, an appearance resembling a “reversed” palmaris (Schuurman and van Gils 2000). A palmaris with double muscle bellies may also occur: in this latter configuration, the two bellies – one proximal and one distal – are separated by a central tendon lying in between (Reimann et al. 1944). The Gantzer muscle (found in approximately 52% of people) is an accessory slip of the flexor pollicis longus which arises from the medial epicondyle in 85% of cases and has a dual origin from the epicondyle and the coronoid process in the rest (Al-Quattan 1996). It inserts onto the ulnar side of the flexor pollicis longus and its tendon. Both anomalous palmaris and Gantzer muscle may contribute to median and anterior interosseous nerve compression.

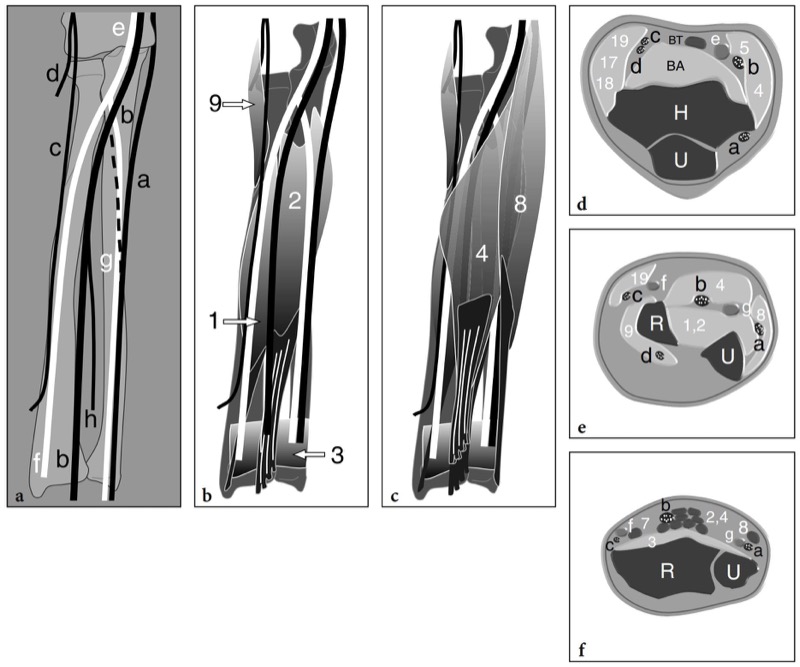

The major nerves and vessels of the forearm are located within or traverse the volar compartment (Fig. 3). The median nerve enters the volar compartment passing between the superficial and deep heads of the pronator teres muscle. It then crosses the ulnar artery and proceeds toward depth to pass below the fibrous arch formed by the flexor digitorum superficialis, the so-called “sublimis bridge”, where it is closely apposed to the deep surface of this muscle. At the middle forearm, the median nerve runs in the midline, as its name indicates, between the superficial flexor digitorum superficialis and the deep flexor digitorum profundus. More distally, at the distal forearm, it becomes more lateral and superficial to enter the wrist. Along its course through the forearm, the median nerve provides motor function to the pronator teres, the flexor carpi radialis, the flexor digitorum superficialis and the palmaris longus. It also sends branches to the proximal part of the flexor pollicis longus and the flexor digitorum profundus. Approximately 5–8 cm distal to the lateral epicondyle, the anterior interosseous nerve is a purely motor nerve which branches off the median nerve at the level of the deep head of the pronator teres. It travels along the anterior surface of the interosseous membrane with the anterior interosseous branch of the ulnar artery, between the muscle bellies of the flexor pollicis longus and flexor digitorum profundus, and then deep to the pronator quadratus. This nerve supplies the flexor pollicis longus, part of the flexor digitorum profundus (for the index and middle finger) and the pronator quadratus. After exiting the cubital tunnel, the ulnar nerve enters the volar compartment of the forearm passing on the anterior surface of the flexor digitorum profundus, under the flexor carpi ulnaris. At the middle of the forearm, it is reached by the ulnar artery and its satellite veins. Thereafter, the nerve and vessels proceed distally together, emerging on the radial side of the flexor carpi ulnaris tendon, between this tendon and the tendon of the flexor digitorum superficialis for the little finger to enter the Guyon canal. In the forearm, the ulnar nerve supplies the flexor carpi ulnaris and the ulnar portion of the flexor digitorum profundus. In up to 30% of people, a crossover of fibers from the median nerve to the ulnar nerve – the Martin–Gruber anastomosis – occurs at the proximal forearm. This anastomosis can be responsible of anomalous innervation of intrinsic hand muscles and thus can lead to unclear clinical presentation of some nerve entrapment syndromes (Fig. 3a).

The two main arteries in the forearm are the radial and the ulnar arteries, which are terminal divisions of the brachial artery (Fig. 3). The ulnar artery travels through the volar compartment with the ulnar nerve. It arises at the level of the neck of the radius, just medial to the distal biceps tendon, and courses deep to the “sublimis bridge” accompanied by the median nerve. At the middle third of the forearm, the ulnar artery traverses posterior to the median nerve toward the medial side of the forearm, where it reaches the ulnar nerve superficial to the flexor digitorum profundus. More distally, it continues its course on the radial side of the ulnar nerve down to the Guyon canal.

Fig. 3a–f. Schematic drawings of coronal (a–c) and transverse (d–f) views through the forearm showing the main nerves (in black) and arteries (in white) and their relationships with surrounding bones and muscles. a Basically, the forearm is crossed by three main neurovascular pedicles: ulnar, central and radial. The ulnar pedicle is formed of the ulnar nerve (a) and the ulnar artery (g); the central pedicle consists of the median nerve (b) and the anterior interosseous nerve (h), the latter arising from it at the middle third of the forearm; the radial pedicle includes the superficial branch of the radial nerve (c) and the radial artery (f). The course of the Martin–Gruber anastomosis is indicated by a dashed line. At the elbow level, note the position of the brachial artery (e) and the posterior interosseous nerve (d). b,c Main forearm muscles located b deep and c superficial to the neurovascular bundles illustrated in a. Note the relationship of the nerves and arteries with the supinator (9), the flexor pollicis longus (1), the flexor digitorum profundus (2), the pronator quadratus (3), the flexor digitorum superficialis (4) and the flexor carpi ulnaris (8) muscles. d–f The relationship of the nerves and arteries with the muscles of the forearm compartments is demonstrated at the level of the elbow (a), the middle (b) and the distal (c) forearm. H, humerus; U, ulna; BA, brachialis; BT, biceps tendon; R, radius

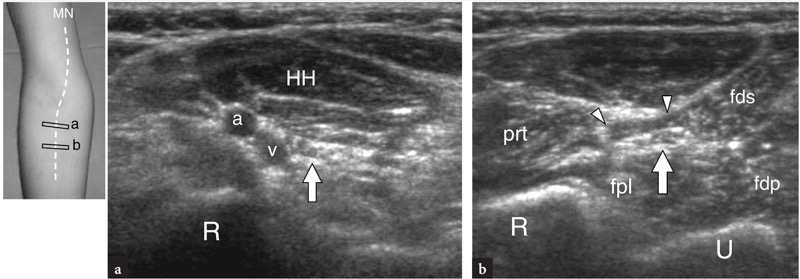

The distal tendons, nerves and vessels are the best US landmarks to recognize the individual muscles located in the volar compartment. Transverse US planes are essential to correctly distinguishing them. At the proximal forearm, US scanning should start in the antecubital fossa where the distal brachial artery and the median nerve can be found along the medial side of the distal biceps tendon. The median nerve is identified based on its and well-defined fascicular echotexture. Sweeping the probe down over it, the median nerve and the ulnar artery become gradually deep running in an echogenic fat-filled cleavage plane under the humeral head of the pronator teres (Fig. 4a). The ulnar head of this muscle appears more distally than the humeral head and is significantly smaller. Remember theat the median nerves runs superficially to the ulnar head while the ulnar artery passes deep to it. When the nerve reaches the flexor digitorum superficialis, it ceases to deepen. In this area, a thin hypoechoic linear structure joining the humeral and ulnar heads of the flexor digitorum superficialis can be seen covering it (Fig. 4b). This structure reflects the fibrous arch (“sublimis bridge”) of the flexor digitorum superficialis and should be examined carefully, as a possible site of median nerve entrapment. At the middle third of the forearm, the median nerve can be easily recognized in the midline and represents a useful key structure to separate the flexor digitorum superficialis, which lies superficial to it, from the flexor digitorum profundus, which lies in a deeper position (Fig. 5a). Both muscles are wide muscles occupying most of the volar compartment at the middle and distal thirds of the forearm (Fig. 5b). They are characterized by four flat intramuscular tendons which appear as hyperechoic stripes and are better individualized as scanning progresses toward the wrist. The flexor carpi ulnaris and the flexor carpi radialis are respectively located just lateral and medial to them (Fig. 5b). Once identified the flexor digitorum profundus, the anterior interosseous nerve and artery can be demonstrated between it and the anterior aspect of the interosseous membrane (Fig. 6). This membrane appears as a thin hyperechoic layer joining the radius and the ulna. The anterior interosseous nerve is a very small hypoechoic dot-like structure consisting of one or two fascicles located just superficial to the interosseous membrane, approximately midway between the radius and the ulna. Once identified, the nerve should be followed cranially on transverse planes up to its confluence with the median nerve. To find the ulnar nerve, a practical approach could be looking at the ulnar artery (possibly switching the color Doppler on) as it leaves the median nerve and traverses the forearm to reach its medial side (Fig. 7a,b). At the distal arm, the ulnar artery lies on the lateral side of the ulnar nerve, covered by the flexor carpi ulnaris muscle (Fig. 7c). In doubtful cases, one of the best ways to identify the bellies of the superficial flexors (flexor carpi radialis, flexor carpi ulnaris and palmaris longus) and the flexor pollicis longus is to start scanning over their distal tendons and then sweep the probe proximally on transverse planes. The scanning technique to examine these tendons and the pronator quadratus will be addressed later.

Fig. 4a,b. Median nerve in the pronator area. a,b Transverse 12–5 MHz US images obtained a at the level of the pronator teres and b at the arcade of the flexor digitorum superficialis. a At the proximal forearm, the median nerve (arrow) passes under the humeral (HH) head of the pronator teres muscle accompanied by the ulnar artery (a) and satellite veins (v). b A few centimeters distally, the median nerve is seen running deep to the fibrous arcade (arrowheads) of the flexor digitorum superficialis (fds), the so-called “sublimis bridge.” Deep to it, note the flexor digitorum profundus (fdp) and the flexor pollicis longus (fpl). The pronator teres (prt) lies lateral to it. R, radius; U, ulna. The photograph at the right of the figure indicates probe positioning over the course (dashed line) of the median nerve

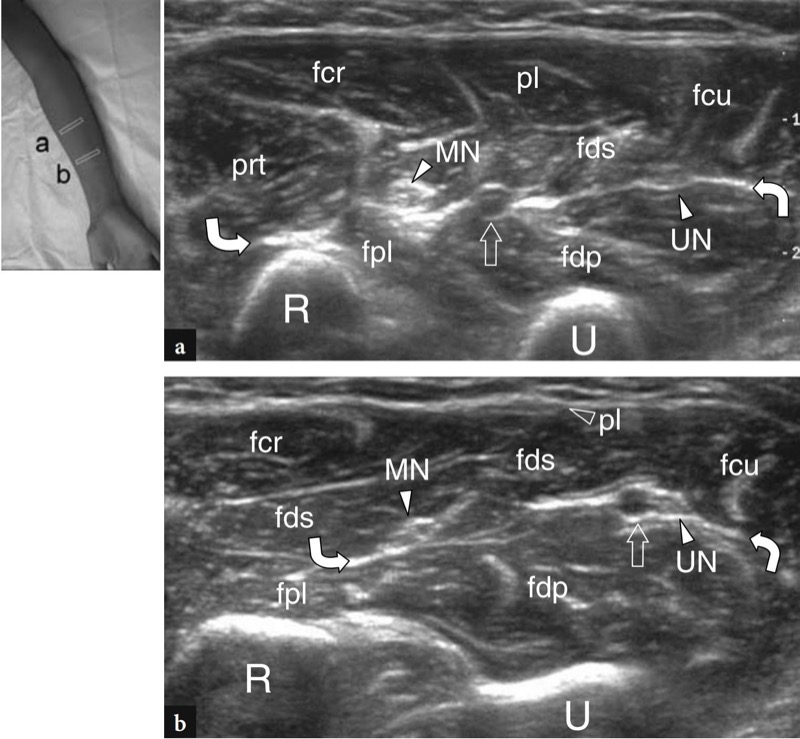

Fig. 5a,b. Volar compartment of the forearm. a,b Transverse 12–5 MHz US images obtained a just distal to the sublimis bridge and b, more caudally, at the middle third of the forearm demonstrate the relationships of the deep muscles – the flexor pollicis longus (fpl) and the flexor digitorum profundus (fdp) – with the superficial muscles – the pronator teres (prt), the flexor carpi radialis (fcr), the flexor digitorum superficialis (fds), the flexor carpi ulnaris (fcu) and the palmaris longus (pl) – of the volar forearm. The two layers of muscles are separated by a transverse hyperechoic cleavage plane (curved arrows) representing an extension of the antebrachial fascia within which the median nerve (MN), the ulnar nerve (UN) and the ulnar artery (straight arrow) are found. From proximal (a) to distal (b), observe the muscle belly of the palmaris longus which continues in a thin superficial tendon. R, radius; U, ulna. The photograph at the right of the figure indicates probe positioning

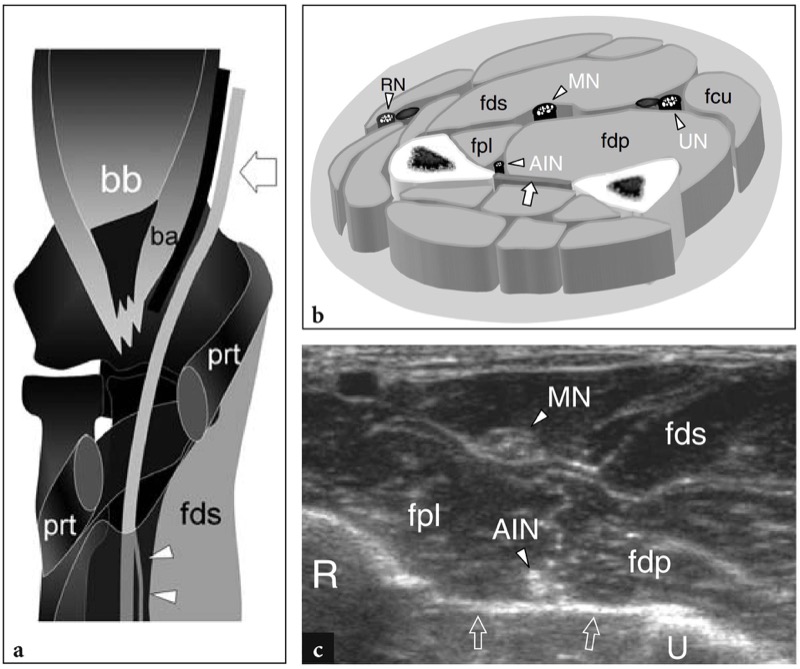

Fig. 6a-c. Anterior interosseous nerve. a Schematic drawing of a coronal view of the elbow after removal of the distal tendon of the biceps brachii (bb) the distal part of the brachialis (ba) and the superficial belly of the pronator teres muscle (prt) reveals the course of the median nerve (arrow) in the pronator area and the origin of the anterior interosseous nerve (arrowheads) deep to the flexor digitorum superficialis muscle (fds). b Schematic drawing of a transverse view through the middle forearm illustrates the close relationship of the anterior interosseous nerve (AIN) with the anterior aspect of the interosseous membrane (arrow) and the bellies of the flexor pollicis longus (fpl) and flexor digitorum profundus (fdp). The anterior interosseous nerve runs in a deeper position compared with the median nerve (MN). Observe the ulnar nerve (UN) which courses between the flexor carpi ulnaris (fcu), the flexor digitorum profundus (fdp) and the flexor digitorum superficialis (fds) muscles. RN, superficial sensory branch of the radial nerve. c Transverse 12–5 MHz US images obtained over the volar compartment at the middle forearm reveal the respective position of the median (MN) and anterior interosseous (AIN) nerves relative to the flexor digitorum superfi cialis (fds), the flexor digitorum profundus (fdp), the flexor pollicis longus (fpl) and the interosseous membrane (arrows). R, radius; U, ulna

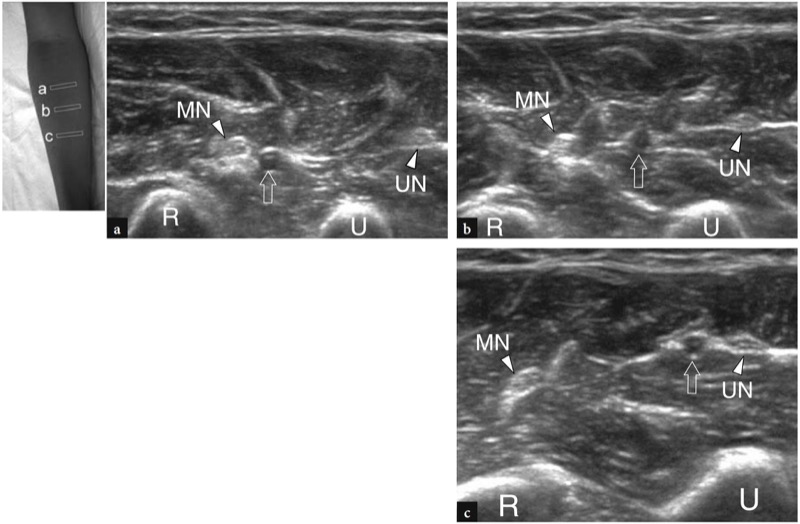

Fig. 7a–c. Ulnar artery. a–c Transverse 12–5 MHz US images obtained from a proximal to c distal reveal the ulnar artery (straight arrow) which traverses the forearm leaving the median nerve (MN) to reach the ulnar nerve (UN). R, radius; U, ulna. The photograph at the upper right of the figure indicates probe positioning

4. DORSAL FOREARM

Similar to the volar compartment, the muscles of the dorsal (posterior) compartment of the forearm, can be arbitrarily divided in two layers: deep and superficial. The deep muscles include the supinator, the extensor pollicis brevis, the abductor pollicis longus, the extensor pollicis longus and the extensor indicis proprius (Fig. 8a). The anatomy of the supinator muscle and its relationships with the posterior interosseous nerve has already been described. The remaining four muscles take their origin from the posterior aspect of the radial and ulnar shaft and from the interosseous membrane distal to the position of the supinator muscle. They insert into the metacarpal (abductor pollicis longus), the proximal (extensor pollicis brevis) and the distal phalanx (extensor pollicis longus) of the thumb, and the middle and distal phalanx of the index finger (extensor indicis proprius) respectively. From lateral to medial, the abductor pollicis longus is the largest and most superficial muscle of the group. Close to it, the extensor pollicis brevis lies in a more distal position and is partially covered by the abductor. The extensor pollicis longus is larger and its tendon is longer than the brevis. Finally, the extensor indicis proprius is narrow and elongated, and lies medial to and alongside the extensor pollicis longus. Apart from the abductor pollicis longus which abducts and extends the thumb, the other deep extensors act to extend the phalanges. From lateral to medial, the extensor muscles of the superficial layer include the extensor digitorum communis, the extensor digiti minimi and the extensor carpi ulnaris (Fig. 8b). In association with the extensor carpi radialis brevis, these muscles share a proximal strong tendon that originates from the lateral epicondyle of the humerus. The extensor digitorum longus and extensor digiti minimi insert onto the middle and distal phalanges of the four medial fingers (extensor digitorum longus) and the little finger (extensor digiti minimi). The extensor carpi ulnaris inserts distally into the base of the fifth metacarpal. On the whole, the superficial extensor muscles are innervated by distal branches of the radial nerve (posterior interosseous nerve).

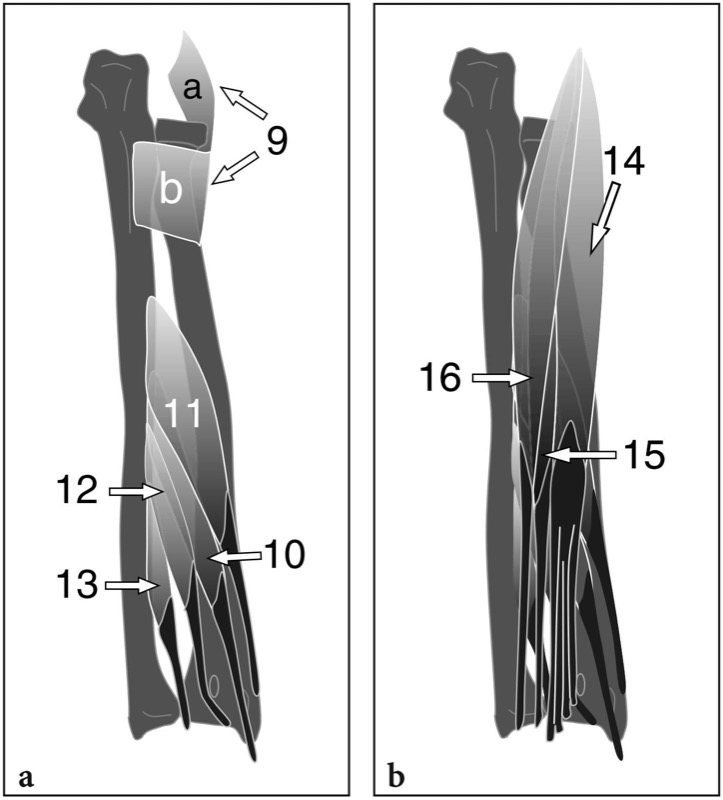

Fig. 8a,b. Schematic drawings of a coronal view of the a deep and b superficial muscles of the dorsal compartment of the forearm. a The deep layer of muscles includes the supinator (9), consisting of two heads – superficial (a) and deep (b) – and, more distally, the abductor pollicis longus (11), the extensor pollicis brevis (10), the extensor pollicis longus (12) and the extensor indicis proprius (13). These latter muscles originate from the posterior aspect of the radial and ulnar shaft and the interosseous membrane. b In a more superficial position, the extensor digitorum communis (14), the extensor digiti minimi (15) and the extensor carpi ulnaris (16) are found arising from the lateral epicondyle of the humerus

As a rule, an accurate and systematic US examination of the dorsal muscles of the forearm should begin at the level of the wrist, where their individual tendons are easily distinguished within the six compartments. Then, US scanning should be performed by shifting the transducer upward to depict the myotendinous junction and the belly of the appropriate muscle to be evaluated. This “retrograde” technique is particularly helpful, even for the experienced examiner, to increase confidence on establishing the identity of the forearm muscles. At the middle third of the dorsal forearm, the muscle bellies of the superficial and deep layers are divided by a transverse hyperechoic septum (Fig. 9). More deeply, the hyperechoic straight appearance of the interosseous membrane and the profile of the radial and ulnar shafts separate the dorsal compartment from the volar compartment (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9a,b. Dorsal compartment of the forearm. a Proximal and b distal transverse 12–5 MHz US images obtained at the middle third of the forearm reveal the two layers of extensor muscles located over the posterior aspect of the interosseous membrane (arrowheads) and seperated by a transverse hyperechoic septum (arrows). From lateral to medial, the superficial layer of muscles includes the extensor digitorum communis (Edc), the extensor digiti minimi (Edm) and the extensor carpi ulnaris (Ecu), whereas the deep layer houses the abductor pollicis longus (Apl), the extensor pollicis brevis (Epb) and the extensor pollicis longus (Epl). R, radius; U, ulna. The photograph at the upper right of the figure indicates probe positioning

5. MOBILE WAD

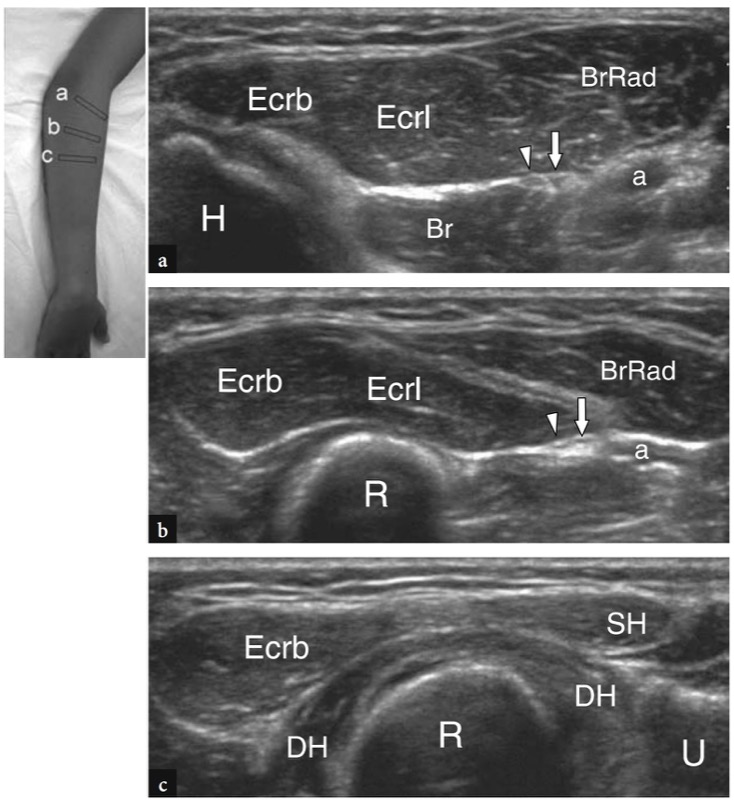

The mobile wad, which is also referred to as the radial group of forearm muscles, contains two wrist extensors (the extensor carpi radialis brevis and the extensor carpi radialis longus) and a forearm flexor (the brachioradialis). These muscles lie in a radial position compared with the ventral and the dorsal muscles of the forearm (Fig. 10). The extensor carpi radialis longus and the brachioradialis are the most superficial and lateral. Both arise from the supracondylar ridge of the humerus and the lateral intermuscular septum, more cranially than the extensor carpi radialis brevis. The brachioradialis is a large muscle forming the lateral boundary of the cubital fossa (Fig. 10a). Distally, it inserts onto the lateral surface of the distal end of radius, just proximal to the radial styloid. Although acting as a flexor of the elbow, the brachioradialis is innervated by the radial nerve, like an extensor muscle. Partially covered by the brachioradialis, the extensor carpi radialis longus lies between it and the extensor carpi radialis brevis (Fig.10). The extensor carpi radialis brevis arises more distally than the longus and is partially overlapped by it. The tendons of the extensor carpi radialis muscles pass through the anatomic snuffbox to insert into the dorsal aspect of the base of the second (longus) and third (brevis) metacarpals. Both muscles extend and abduct the wrist joint. The US scanning technique to examine the muscles of the mobile wad does not differ significantly from that used for the dorsal compartment (Fig. 11).

Fig. 10a,b. Schematic drawings of a coronal view of the mobile wad compartment of the forearm illustrated a without and b with removal of the brachioradialis muscle. a The brachioradialis (19) is a large palpable muscle arising from the supracondylar ridge of the humerus and the lateral intermuscular septum which continues distally with a long and strong tendon. b More deeply, the extensor carpi radialis brevis (17) and the extensor carpi radialis longus (18), the first arising from the lateral epicondyle, the second from the supracondylar ridge of the humerus, descend in the forearm in association with the brachioradialis

Fig. 11a–c. Mobile wad compartment of the forearm. a–c Series of transverse 12–5 MHz US images obtained at the elbow and the proximal forearm from a proximal to c distal reveal the bulk of muscles of the mobile wad, consisting of the brachioradialis (BrRad), the extensor carpi radialis longus (Ecrl) and the extensor carpi radialis brevis (Ecrb). The relationships of these muscles with the posterior interosseous nerve (arrowhead), the superficial sensory branch of the radial nerve (arrow), the radial artery (a) and the superficial (SH) and deep (DH) heads of the supinator muscle are shown. Br, brachialis; H, humerus; R, radius; U, ulna. The photograph at the upper right of the figure indicates probe positioning

The superficial sensory branch of the radial nerve and the radial artery are located between the mobile wad compartment and the volar compartment of the forearm. After branching off the main trunk of the radial nerve, the superficial radial nerve initially travels with the radial artery deep to the brachioradialis. It then passes between that muscle and the extensor carpi radialis longus to emerge from under the lateral boundary of the brachioradialis (Fig. 12a). At the distal forearm, this nerve pierces the antebrachial fascia and becomes subcutaneous, providing sensory innervation for the dorsum of the hand, the first web space and the proximal phalanges of the three radial fingers (Fig. 12b,c). While crosing the fascia, the radial nerve can be compressed in the scissoring of the brachioradialis and the extensor carpi radialis longus during pronation and supination of the forearm. At this site, dynamic US can show transverse sliding of the nerve during pronation and supination movements. The radial artery is located more lateral and superficial compared with the ulnar artery. Initially, it is covered by the brachioradialis and then becomes more superficial at the middle and distal thirds of the forearm, where it runs between the brachioradialis and the flexor carpi radialis tendons.

Fig. 12a–c. Superficial branch of the radial nerve. a–c Series of transverse 15–7 MHz US images obtained at the distal forearm from a proximal to c distal. a The superficial radial nerve (arrow) courses just deep to the antebrachial fascia (arrowhead) between the brachioradialis muscle (BrRad) and tendon (asterisk) and the extensor carpi radialis longus (ECRL). b More distally, it crosses the fascia and c moves to the subcutaneous tissue. R, radius. The photograph at the right of the figure indicates probe positioning

6. FOREARM PATHOLOGY

Similar to the arm, musculoskeletal pathology affecting muscles and tendons is uncommon in the forearm and, for the most part, should derive from open wounds, contusion or penetrating trauma. Although unusual, there are some peculiar pathologic conditions affecting the median nerve in the proximal forearm as well as its main divisional branch, the anterior interosseous nerve, which may give rise to pain in the volar aspect of the forearm and weakness of the innervated flexor muscles. These conditions include pronator syndrome and anterior interosseous nerve syndrome. To the best of our knowledge, the latter is the only one which has received attention in the imaging literature.

7. VOLAR FOREARM: PRONATOR SYNDROME

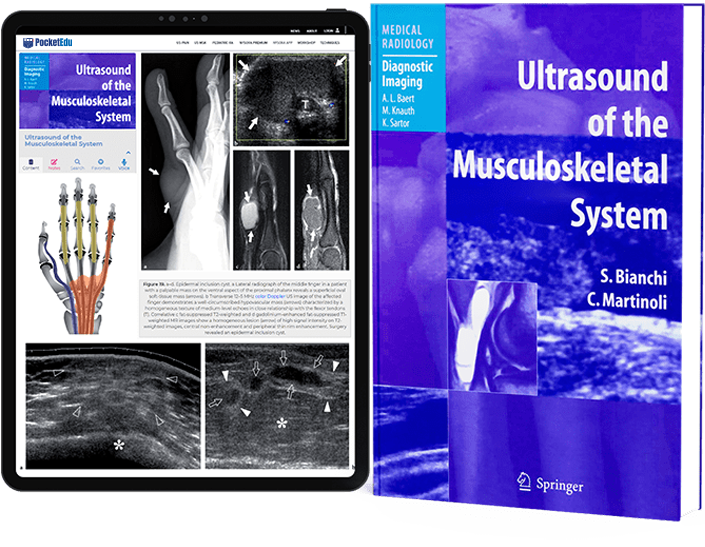

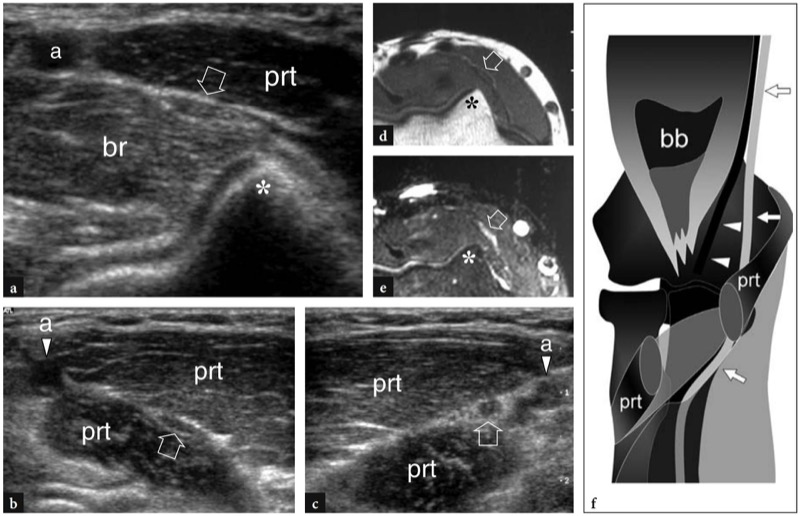

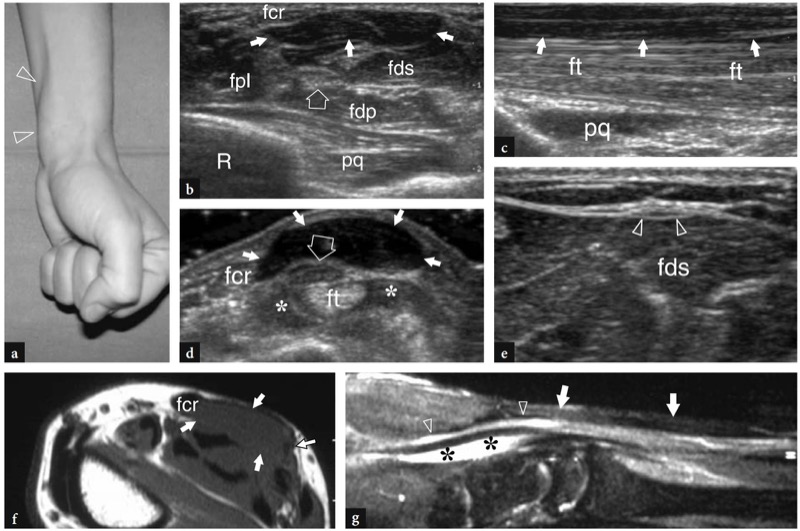

Pronator syndrome is an insidious entrapment neuropathy of the median nerve in the proximal volar forearm. In this syndrome, the compression may occur either in the area where the nerve traverses deep to the lacertus fibrosus of the biceps, or as it crosses between the two heads of the pronator teres, or as it passes under the fibrous arch (sublimis bridge) of the flexor digitorum superficialis. Hypertrophy of the pronator teres, aberrant fibrous bands connecting the pronator teres to the tendinous arch of the flexor digitorum superficialis or the flexor carpi radialis with the ulna, direct trauma and forearm–elbow fractures have been reported as the possible causes. The main clinical features of this uncommon and somewhat controversial clinical entity are aching in the proximal volar forearm or distal arm, typically exacerbated by repetitive pronation and supination movements paresthesias in one or more of the radial three and a half fingers and weakness of the flexor pollicis and abductor pollicis longus with intact forearm pronation. Nocturnal pain (so typical of carpal tunnel syndrome) is usually not seen in these patients. Diagnosis of pronator syndrome is essentially based on clinical signs and symptoms and should be considered seriously when median nerve disturbances are not relieved after carpal tunnel release. The role of diagnostic imaging has not yet been assessed in this neuropathy. US could reinforce the likelihood that a pronator syndrome is present, when asymmetry of the pronator teres (the belly of the affected side larger than the contralateral side) and local flattening, distortion and an abnormal course of the nerve between the heads of the pronator or beneath the arcade of the flexor digitorum superficialis are seen (Fig. 13). Initial treatment of pronator syndrome is conservative because many patients recover over the course of a few months. In the remaining patients, surgical decompression of the nerve below the elbow (possibly associated with carpal tunnel release) is successful in many cases.

Fig. 13a–f. Pronator syndrome in a patient with persisting symptoms of median neuropathy irradiated to the volar forearm and wrist after carpal tunnel release. a Transverse 12–5 MHz US image obtained at the elbow level, over the medial edge of the humeral trochlea (asterisk) demonstrates a flattened median nerve (arrow) presenting with an abnormal medial course between the pronator teres (prt) and the brachialis (br). a, brachial artery. b More distally, in the pronator area, transverse 12–5 MHz US image shows the flattened median nerve (arrow) coursing between the two heads of the pronator teres (prt). The nerve lies more medially than expected and not so closely associated with the ulnar artery (a). This anomaly suggested positional entrapment of the median nerve in the pronator area. c Contralateral normal side. Note the rounded cross-sectional profile of the normal median nerve (arrow) which runs adjacent to the ulnar artery (a). prt, pronator teres. d,e Transverse d T1-weighted and e fat-suppressed T2-weighted MR images of the elbow confirm flattening of the median nerve (arrow) which appears slightly hyperintense in the T2-weighted sequence. Asterisk, medial edge of the humeral trochlea. f Schematic drawing of a coronal view of the elbow after removal of the distal tendon of the biceps brachii (bb), the brachialis muscle and the superficial belly of the pronator teres (prt) reveals the abnormal course of the median nerve (arrows) in the pronator area described in this particular case. Arrowheads, brachial artery.

8. ANTERIOR INTEROSSEOUS NERVE SYNDROME

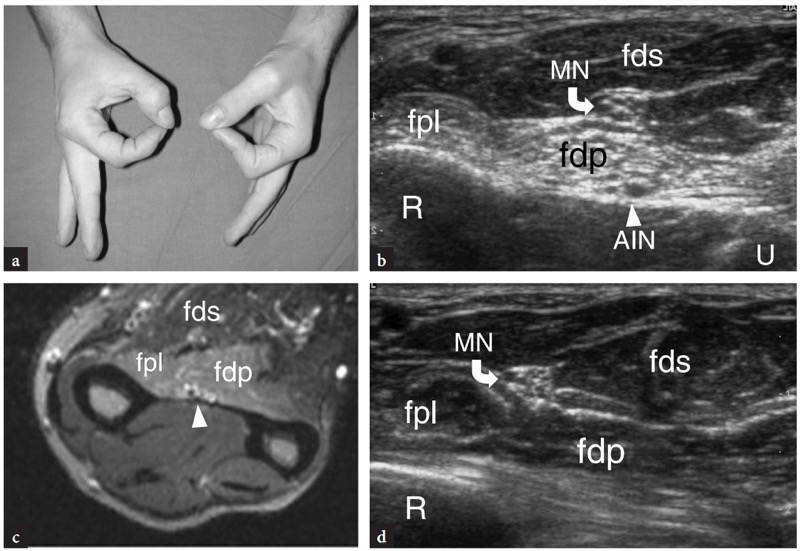

The entrapment of the anterior interosseous nerve in the forearm, a condition also known as the Kiloh–Nevin syndrome (Kiloh and Nevin 1952), occurs where the nerve branches off the median nerve, in proximity to the pronator teres and the tendinous bridge connecting the heads of the flexor digitorum superficialis (Stern 1984). The anterior interosseous nerve may be compressed alone or together with the main trunk of the median nerve by a variety of conditions, such as fibrous bands arising from the pronator teres and the flexor digitorum superficialis, hypertrophied anomalous muscles (Gantzer muscle) and accessory tendons from the flexor digitorum superficialis to the flexor pollicis longus. Similar to pronator syndrome, an isolated anterior interosseous neuropathy leads to pain in the volar forearm and difficulty in performing pinching movements with the digits (formation of a triangle instead of a circle with the first two digits) and handwriting. The thenar muscles are spared and there is no sensory loss (Fig. 14a). Muscle weakness is typically limited to the flexor pollicis longus, the flexor digitorum profundus to the index finger (middle finger also involved in 50% of cases), and the pronator quadratus (Fig. 14a). Differential diagnosis includes brachial plexus lesion and selective injury to the fibers of the median nerve at the elbow or in the arm that are destined to become the anterior interosseous nerve. In general, US examination of the anterior interosseous nerve is inconclusive in the absence of a mass because this nerve is too small and located deeply in the forearm. In rare cases, however, the nerve and its fascicles may appear swollen compared with the contralateral side (Fig. 14c). Besides direct nerve assessment, US diagnosis of an overt anterior interosseous neuropathy may be suggested by loss in bulk and increased reflectivity of the innervated muscles: the flexor pollicis longus, the flexor digitorum profundus and the pronator quadratus (Fig. 14d) (Grainger et al. 1998; Hide et al. 1999; Martinoli et al. 2004).

Fig. 14a–d. Anterior interosseous nerve syndrome in a young woman with previous contusion trauma at the volar forearm and inability to perform pinching movements with the thumb and the index as shown in a. b Transverse 10–5 MHz US image obtained through the middle forearm demonstrates abnormally swollen fascicles (arrowheads) of the anterior interosseous nerve (AIN) over the interosseous membrane. Note the loss in bulk and increased reflectivity (arrows) of the flexor digitorum profundus (fdp) and flexor pollicis longus (fpl) muscles. Such changes are not appreciated in the flexor digitorum superficialis (fds) MN, median nerve; R, radius; U, ulna. c Corresponding fat-saturated T2-weighted transverse MR image shows the swollen hyperintense nerve. d Normal contralateral side. Surgery revealed the entrapment of the anterior interosseous nerve (AIN) by a fibrous band arising from the flexor digitorum superficialis

9. OTHER COMPRESSION NEUROPATHIES

Because of their free, unconstricted course, the radial and ulnar nerves are rarely compressed in the forearm. A reported site of compression of the sensory branch of the radial nerve is its point of emergence between the tendons of the brachioradialis and the extensor carpi radialis longus in the distal forearm. Repeated pronation and supination of the forearm is believed to be contributory to positional impingement of the nerve in the scissoring of these two tendons. From the biomechanical point of view, the nerve is anchored by fascia at this site and cannot adjust its position as the adjacent tendons do. Patients complain of pain and burning sensation over the dorsoradial aspect of the forearm, which increase in intensity with palmar flexion and ulnar deviation of the wrist or quick repeated pronation and supination movements. More distally, the entrapment of the sensory branch of the radial nerve may occur around the radial aspect of the wrist, so-called Wartenberg syndrome. On the mid-distal forearm, ulnar nerve compression may occur from casts positioned for wrist fractures or may be related to direct injuries, including contusion trauma (from a direct blow) or penetrating wounds. In contusion trauma, there may be discrepancy between severity of clinical picture and normal electrodiagnostic studies. Tinel’s sign is usually positive on the ulnar aspect of the forearm. US can assess whether a nerve abnormality (fusiform neuroma) exists at the lesion site and may help the clinician to decide which is the most appropriate treatment (conservative vs. operative) to be instituted. In the area between the pronator and the carpal tunnel, the median nerve may occasionally be compressed by space-occupying masses (i.e., lipomas, ganglion cysts) or anomalous muscles. Among them, a reversed palmaris can produce a mass effect on the flexor tendons and the median nerve at the distal forearm (Depuydt et al. 1998). In these cases, US is an ideal means to reveal dynamic impingement of the median nerve by the anomalous muscle at rest and during contraction (Fig. 15).

Fig. 15a–g. Reversed palmaris muscle and carpal tunnel syndrome. a Photograph of a woman presenting with a fusiform soft tissue lump (arrowheads) in the volar wrist and clinical symptoms of carpal tunnel disease. The lump increases in size and stiffness while clenching the fist. b Transverse and c longitudinal 12–5 MHz US images over the mass reveal an additional muscle belly (white arrows) over the flexor digitorum superficialis muscle (fds) and tendons (ft), reflecting a reversed palmaris. In a, observe the median nerve (open arrow) and other adjacent deep muscles, the flexor pollicis longus (fpl), the flexor digitorum profundus (fdp) and the pronator quadratus (pq). R, radius. d Transverse 12–5 MHz US image over the anomalous muscle obtained during contraction. Active contraction leads to an increased thickness of the muscle belly. This change can be easily palpated at physical examination and would lead to compression on the underlying median nerve (arrow). Note tenosynovial effusion (asterisks) in the sheath of the flexor tendons (ft) and the normal flexor carpi radialis tendon (fcr). e Transverse 12–5 MHz US image obtained at the proximal forearm demonstrates a long thin tendon (arrowheads) of the palmaris instead of the muscle belly. The anomalous tendon is located superficial to the flexor digitorum superficialis. f Axial T1-weighted and g sagittal fat-suppressed T2-weighted MR images reveal the anomalous reversed palmaris (arrows), a hyperintense appearance of the median nerve (arrowheads) in the T2-weighted sequence and fluid effusion (asterisks) in the flexor tendon sheath reflecting tenosynovitis

10. PENETRATING INJURIES

Except for major trauma with fractures and extensive laceration of soft tissues, there are no specific musculoskeletal disorders affecting tendons and muscles (such as overuse injuries, compartment syndromes and tears) in the forearm. The main nerves are covered by large muscle bellies (i.e., the flexor carpi ulnaris for the ulnar nerve, the flexor digitorum superficialis for the median nerve, the brachioradialis for the radial nerve) for the majority of their course and, therefore, are somewhat protected from external trauma. In general, the critical area for nerve and tendon injuries is the distal forearm where these structures become more superficial and are, therefore, exposed to penetrating wounds (Figs. 16,17). Nevertheless, deep open trauma caused by sharp objects or glass fragments may reach and damage tendons and nerves everywhere. Often, two or more contiguous structures (i.e., ulnar nerve and ulnar artery) may be wounded at the same time by such trauma. In general, the smaller the damaged structure, the most likely it will be completely sectioned by a penetrating wound. Differentiation between complete and partial tears of muscles and tendons is easily accomplished with US because a significant retraction of the torn tendon ends usually takes place when the lesion is complete.

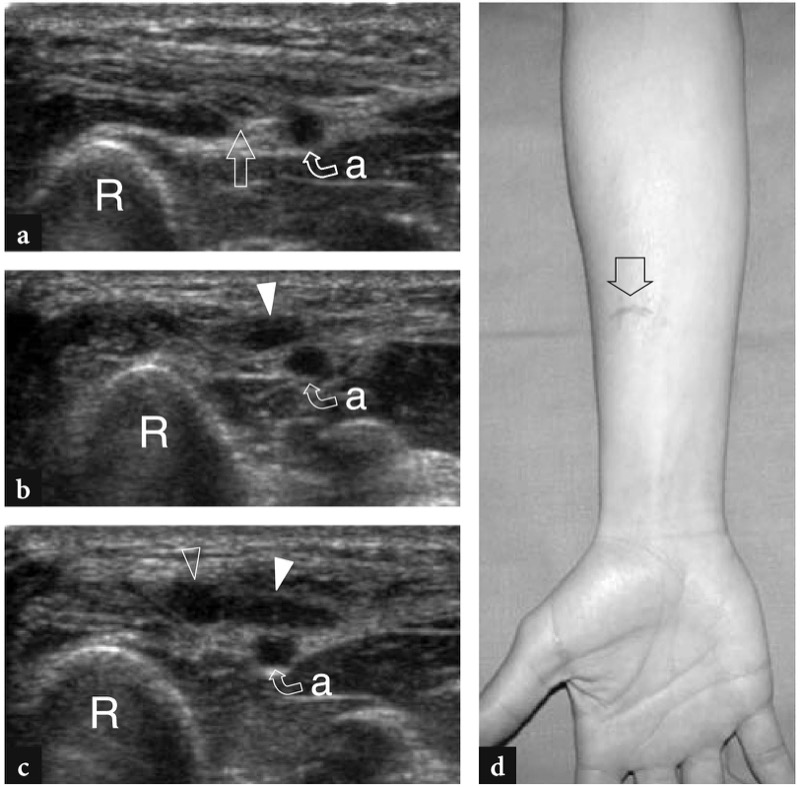

Fig. 16a–d. Flexor carpi radialis tendon tear. a Photograph of a boy complaining of weakness of wrist flexion and a soft tissue lump (white arrows) on the volar aspect of the wrist after receiving a penetrating wound (open arrow) in the middle forearm by a sharp object. b Longitudinal and c transverse 12–5 MHz US images over the distal lump reveal a retracted tendon end (arrows) of the flexor carpi radialis which appears swollen and diffusely hypoechoic. d At the level of the wound, transverse 12–5 MHz US image demonstrates an empty sheath (arrowheads) of the flexor carpi radialis tendon

Fig. 17a–d. Complete tear of the superficial branch of the radial nerve by a glass wound. a–c Series of transverse 12–5 MHz US images of the middle third of the forearm obtained a proximal to, b at the level of and c distal to the cut line. In a, note the superficial course of the radial nerve (straight arrow) which runs closely associated with the radial artery (a). In b and c, two adjacent neuromas are found connected with the proximal (white arrowhead) and distal (open arrowhead) stumps of the severed nerve. R, radius. d Photograph shows the cut line (arrow) at the middle third of the forearm.

11. DORSAL FOREARM AND MOBILE WAD

Owing to a differential diagnosis list which mainly includes wrist problems (i.e., de Quervain disease and Wartenberg neuropathy), the most important tendinopathy of the mobile wad compartment affecting the tendons of the extensor carpi radialis brevis and longus as they traverse the components of the first dorsal extensor tendon compartment, so-called intersection syndrome.