What happens when a BLUE-protocol is performed or when any ultrasound test is done on a critically ill patient?

1. INTRODUCTION

What happens when a BLUE-protocol is performed or when any ultrasound test is done on a critically ill patient?

First, we see an “unusual” patient. Unusual is a term from the traditional perspective of the radiologist or the cardiologist. Our patient is in high distress (dyspneic, agitated, etc.) or already sedated. As opposed to ambulatory patients, who can be positioned laterally with inspiratory apnea for studying the liver, or sitting for pleural effusions, or again with legs down for venous analysis, etc., no cooperation is awaited. Apnea cannot be obtained: the patient is either mechanically ventilated, or dyspneic, or encephalopathic.

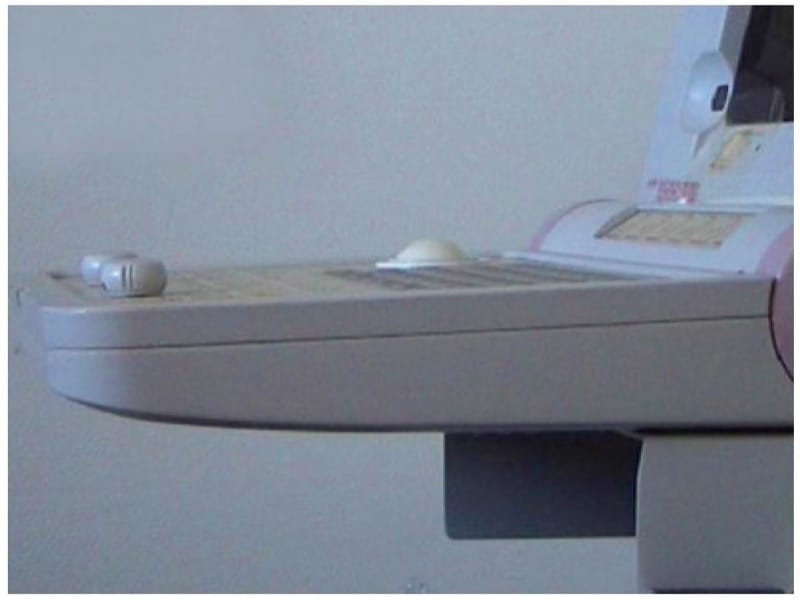

Then, we have to access the patient. When surrounded by multiple life-support devices (ventilator, hemodialysis, pleural drainage, etc.), the machine must be as narrow as possible. This is why we keep on using our 32-cm- width (with cart) 1992 machine. This is why laptops, which may be 5 cm high but 50, 60, or worse wide (we measured up to 76 cm), are not our preference (especially in extreme emergencies). Each saved lateral cm makes our work easier. In hospitals, ceilings are high enough – the height is not a problem.

Usually, lung ultrasound in a dyspneic patient is perfectly feasible using our unsophisticated, instant response system.

The barrier is lowered. We don’t need to tear away the electrodes because our nurses have been taught to apply them at nonstrategic areas, i.e., the shoulders and sternum. The ECG is not disturbed. This slight detail makes one less useless loss of time (and costs).

Now, just before scanning our patient, we can note a remarkable and providential feature of ultrasound in the critically ill: most can be done in the supine position. The supine patient offers wide access to the most critical areas: the optic nerve, maxillary sinus, anterior and lateral areas of the lungs, most deep veins, heart, abdomen, etc. Turning a patient 90° is never easy nor fully harmless nor fast (and the BLUE-protocol is a fast protocol). The “hidden side” of the ventilated patient, i.e., the posterior disorders (effusion, consolidation), is a usual limitation, which we deeply reduce by optimizing the tools for making this setting like any other. The choice of our unique 88-mm-long probe is the main key for reducing the hidden face of the lung. For assessing the PLAPS-point (detection of most pleural effusions and posterior consolidations), the elbows are gently spread from the chest in order to facilitate a slight rotation.

Then, the scanning begins. With our compress soaked with Ecolight on the patient’s skin (the bed would “drink” it and oblige to more soakings, i.e., loss of time) and our probe in hand, we scan what is required: the lungs and the veins for the BLUE-protocol and the heart first for the FALLS-protocol. We follow standardized points for expediting the protocol and make more comprehensive scanning once the clinical question is answered (time permitting). Each change of area (e.g., from deep lungs to femoral veins) takes two seconds: no time for swapping the probe and no time for taking the bottle of gel; we just take our soaked compress and treat the next area to scan. We always use both hands, permanently.

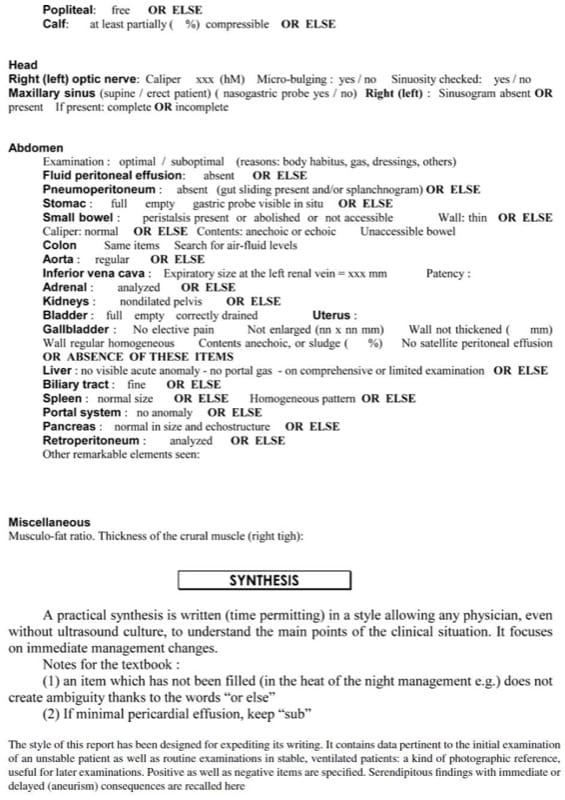

In good conditions, the whole body can be analyzed in less than 10 min using our probe (the BLUE-protocol takes 3 min or less; sometimes it is concluded after 5 s). The examination can be recorded in real-time without losing time taking figures. When the question is focused (e.g. left pneumothorax or not), a few seconds are required. Table 1 shows a suggestion of ultrasound report made with this spirit.

The critically ill patient is – in a way – privileged with respect to ultrasound. The sedation facilitates all interventional procedures. Traditional obstacles (the gas barrier) turn into advantages since lung ultrasound is the main topic of this textbook. Our study showed a 92 % feasibility for all usual targets [1].

Table 1. Usual report of whole-body critical ultrasound.

2. DISINFECTION OF THE UNIT: NOT A FUTILE STEP

Prevention of cross-infections is a major care in the ICU, and this regards ultrasound. When we see these laptops plenty of buttons, we wonder how they can be kept clean. Our protocol is logical and easy to follow, aiming at a 95 % efficiency (96 % would need much more work; 97 % would be followed by nobody, resulting in dirty machines). We just ask to the user to create some good sense refl exes.

For instance, one may either say “do not touch useless things with contaminated hands” or make the list of the mistakes: pushing the machine by the hand for centimetric moves (we use our feet at low areas), leaving the contact product on the bed (it should never leave the cart), touching for no reason the on-site bottle of disinfectant, etc. Then, the reflexes become automatisms.

Our compact equipment really helps. Its keyboard is flat, no protrusion of buttons. Its unique probe is easily cleaned (several intricate probes, no). Such equipments exist since 1982 (ADR-4000).

We define as “dirty areas” the few parts which will be touched during an examination, probe, keyboard, and contact product, if used several times (Fig. 1). We define as “clean areas” all other parts of the ultrasound machine and avoid to touch them without strong reason during the examination.

Fig. 1 Bacteriological partition of our unit. Only the circled parts need to be touched and should therefore be disinfected after use. See this flat keyboard, immediately cleaned. One single probe can efficiently be cleaned before insertion on its stand. There is no need to touch any of the other parts ( with crosses ) during the examination (or if so, they should just be cleaned after).

Once the work is finished, the patient is covered again and the barrier up again; we leave the probe on the bed when the patient is quiet (if not, we leave the probe in a special place). We come back with clean hands. Our on-site disinfectant product (in a dedicated place, never handled during the examination) is poured onto a simple not woven compress which allows an efficient work. The stock of compresses is located in a “clean area” of the machine. Traditional moist wipes are not as efficient as our system of well-soaked compress. Then, the work of disinfection is simple: only the “dirty parts” are cleaned:

- The flat keyboard is cleaned in a few seconds (Fig. 2).

- The (unique) probe is cleaned from the cable to the probe. The cleaned probe is then inserted onto the stand. The stand is clean by definition because the user always cleans the probe before laying it on the stand. An efficient cleaning of a stand is difficult.

- The contact product, if used twice, is cleaned (sophisticated note: the body of the bottle, easy to clean, is a “dirty area.” The top, everything but flat, is difficult to clean and is defined as a “clean area,” never to be touched during an examination. Once hands are clean, it is easy to take the bottle from the clean top and wipe the dirty body, making no asepsis fault).

Fig. 2 A flat screen. This kind of screen, available in our 1982 ADR-4000 and 1992 Hitachi-405, is cleaned in a few seconds.

It is not forbidden to touch “clean areas” of the unit without necessity. Putting soiled hands on clean areas, leaving the contact product bottle lying on the bed, or again handling the disinfectant by soiled hands is allowed, provided the user carefully cleans everything after examination. This is just a loss of energy. When the steps are done in a logical order, the cleaning time is estimated at 30 s and the unit remains clean.

Which disinfectants do we pour on our compress? We do not like to see products devoted for the grounds; they may be too detergent for our subtle equipment, especially the delicate silicone part. Manufacturers have always given us obscure answers. We were obliged to take some risk and build up experience with years. We have been using a 60 % alcohol-based alkylamine bactericidal spray with neutral tensioactive amphoteric pH on the microconvex probe of our Hitachi EUB-405 unit since 1995, and our probe has still not shown any damage (Fig. 3). Some authors have proposed 70 % alcohol as a simple and effcient procedure [ 2 ], but a majority of authors find it risky for the probes and not effective enough. An aldehyde-based and alcohol-based spray has been advocated [3], but this is a questionable approach if this blend fixes the proteins. The gel is a culture medium for bacteria. Many constraining procedures have been designed for carefully withdrawing all marks of gel. Some advocate an absorbent towel between two patients [4]. In the ICU, this solution seems clearly questionable. Since we do not use gel, these complicated procedures can be forgotten.

Fig. 3 How the top of our unit is optimized. This simple figure shows several points. First, our analogic unit, not a laptop, has a top, and we can see how this top is exploited, optimal space management in the usual dimension, the width: three tools, including one single probe (P), allowing to avoid these lateral stands which expand the width of the laptop (and other) machines, one (gelless) contact product (C), and one disinfectant (D) well tolerated since years and years by the probe. Second, it shows how the three tools we permanently use are solidly fixed on allotted holes, preventing any fall during transportation. Third, the unique probe concept allows precisely this configuration, avoiding these lateral stands which take lateral space (see through the textbook). Fourth, here is featuring the 2008 update of our 1992 technology (they just added some cosmetic changes: this purple color on the body).

3. WHEN IS IT TIME TO PERFORM AN ULTRASOUND EXAMINATION

The simple admission to an ICU is a sign of gravity. Ultrasound is fully part of the physical examination and is practiced during (sometimes after) (sometimes before, in cardiac arrest) this basic step. Only beneficial information can emerge from it (read Anecdotal Note). The utility of ultrasound has been proven in the critically ill. We expect each patient to benefit from several examinations during any long stay – not to say everyday or more.

For being schematical, the first contact provides the initial diagnosis. It includes any procedure, either diagnostic (puncture of suspect site) or venous line insertion. The following step is the follow-up, done ad lib, for early detection of the usual complications (pneumonia, sinusitis, thromboses, etc.). Routine, repeated ultrasound tests in the ICU are like taking a “photograph” of the patient. A test limited to one point (e.g., full bladder) takes a few seconds. The CLOT-protocol is a typical application of this concept.

4. SINCE WHEN DO WE PERFORM THESE WHOLE-BODY ULTRASOUND EXAMINATIONS: SOME HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVES

Our hospital is probably the first where an ultrasound unit, belonging to the ICU for cardiac investigations (the effi cient work of François Jardin), was used on the whole body by the intensivist, for immediate management. Our princeps study, sent in 1991, found a 22 % utility rate with immediate therapeutic changes in consecutive patients [5]. This percentage is confirmed in clinical settings [6] as well as, interestingly, the 31 % rate in a study considering unexpected autopsy findings from ICU patients [7]. Our 22 % rate was a minimal, since it did not include unpublished applications, i.e., mainly lung ultrasound and other fields (optic nerve, sinusitis, etc.), nor the benefit of repeated examinations for monitoring critically ill patients (venous thromboses, e.g.), nor cardiac results, nor interventional procedures, nor negative findings with immediate change in management (e.g., postponing CT when the question was answered), nor the decrease in radiations (X-rays), nor postponing of painful tests (arterial blood gas), etc. Performed today, this study would clearly quadruple this initial value of 22 %.

5. ANECDOTAL NOTES

In ancient times, but far after the era of clinical ultrasound, it was not rare to see in prestigious institutions the admission of a patient by a team who knew the work and did not need bedside ultrasound. The patient, definitely critically ill, worsened day after day in spite of the therapy (done from a wrong diagnosis), eventually the team decided to practice an ultrasound test (at worst, sending the patient to the radiology department and to an inexperienced radiologist) (at best in the ICU by a skilled ICU member), and the diagnosis was done, just a bit late, once the inflammatory cascade was ongoing. We use the past, because we hope such a scenario would be difficult to find, nowadays.