The world of medicine is full to the brim with expert literature, but it isn’t every day that a key opinion leader sets out to write something completely out of the ordinary. We recently sat down with Dr. Steven Orebaugh, an anesthesiologist and an author, as he shared his journey from medical to fantastical with the release of his second novel, The Stairs on Billy Buck Hill.

Opioids are killing Americans in unprecedented numbers. While physicians are often implicated among the many causes of this scourge, little attention is paid to the potential for doctors and nurses to become addicts themselves. Anesthesiologists and nurse anesthetists, who administer opioids with great regularity, are among the most susceptible providers. “The Stairs On Billy Buck Hill” shares one physician’s travails as he progresses from the carefully controlled, recreational use of opioid pills, to the brazen theft of fentanyl from his patients in the operating room, a treacherous descent that leads to the destruction of his career, his social standing, and very nearly himself.

- Steven, what inspired you to write this book?

I’ve been working on this book for about six or seven years. I had a number of colleagues and trainees that were in our program who became addicted to opioids. In all of those cases, there were tragic endings. Not necessarily tragic in terms of losing their life, although we did lose one of our interns. Many lost their careers, caused a major social upheaval, and changed the course of their lives dramatically. In all of those cases, I have to say, I did not realize the problem existed. It was subtle.

It’s a problem for a lot of US hospitals. If you look at some of the data – although admittedly old – in the later part of the last century, a couple of psychiatric studies came out in psychiatry literature suggesting that about 15% of doctors have a substance abuse problem. Spreading the word on this may have decreased the numbers, or at least I hope. The American Nursing Association (ANA) had a similar figure for nurses sometime in the 1980s.

As I learned more about it, I realized that it was a much more major problem than I had ever known, and that inspired me to write this book.

- How often do you think this happens – in anesthesiology in particular – that people get hooked on the very drug that they use to treat their patients?

I don’t think it’s a common thing, but it does happen. In our specialty, we have such ready availability of these drugs, and typically there’s not someone in there watching exactly what we do from moment to moment. That factor alone sets us apart from a lot of other acute care practitioners who may not have the alone time with opioids that we have.

The figures I had are from the late eighties and nineties and probably don’t apply today. People are smarter today, and, compared to the time when I was a resident, the degree of watchfulness and control by the pharmacy people, the administrators, and even the electronic devices are all much stricter.

Statistically, it’s not a huge problem, probably less than 1%, but I was a little surprised when two of our major publications in the United States did not want to feature an excerpt from the book because they felt that it would reflect badly on the specialty. It’s surprising that they would not be interested in making others more aware, to act as a cautionary tale; that by popularizing the book, you’d be helping people to avoid the problem, but they did not see it that way.

- In the book, you have a detailed description of how Kurt and his girlfriend Laura, inject themselves when going to a party and the euphoria that ensues. So, can I ask, have you ever experienced opioids yourself as a patient?

Oh, sure, and each time that I did, I was acutely aware of just how amazing the feeling was. Each time, I would think to myself, “I understand now why people get addicted to these drugs” because this feeling was outside the range of what I felt were normal human emotional experiences; it was something otherworldly.

So I was trying to capture that in some of these descriptions in the book because I have previously felt like ” I do understand how people could lose their way and want that.”

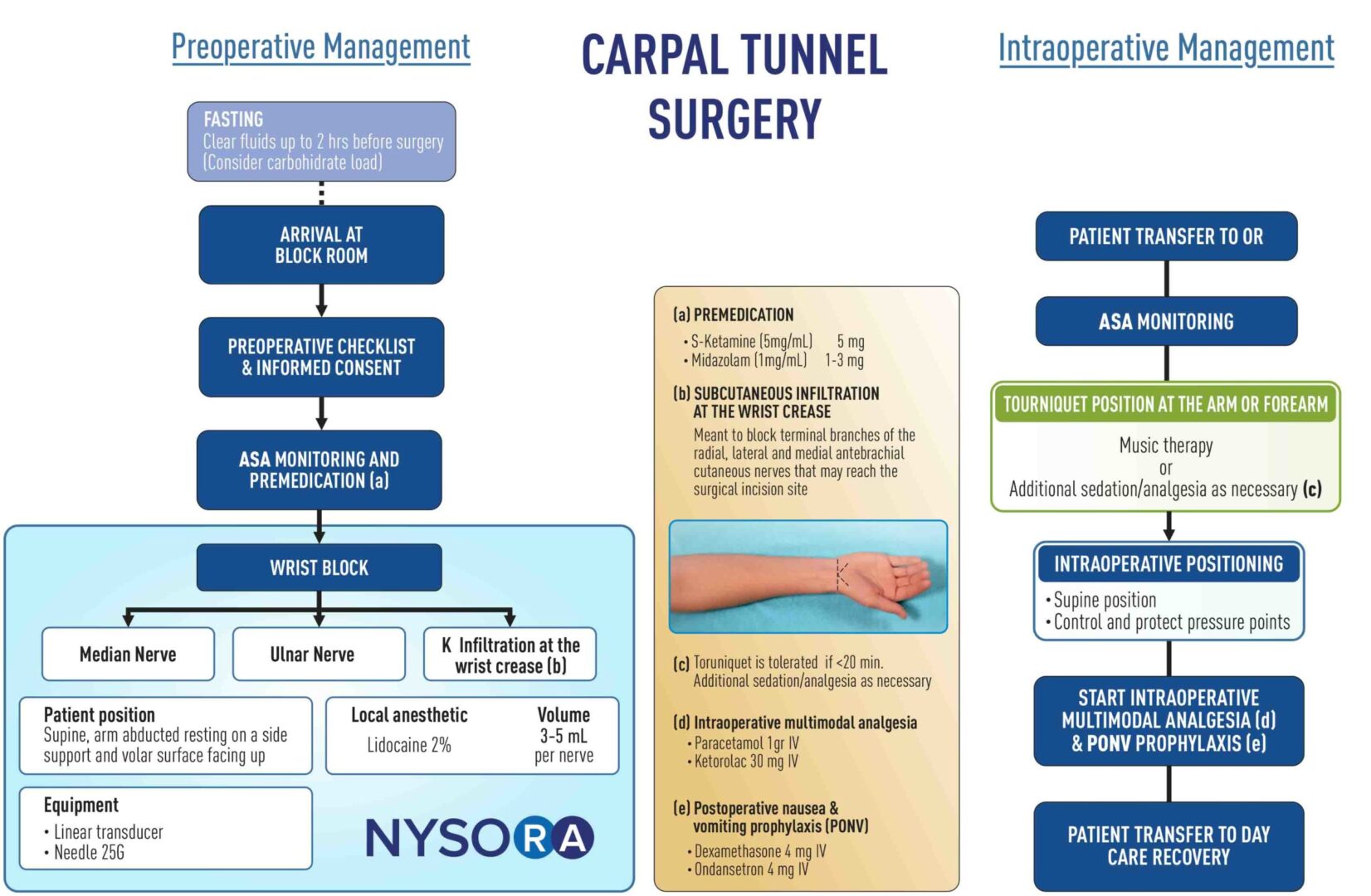

- Steven, you practice regional anesthesia. You’re one of the experts and promoters of these regional anesthesia techniques that avoid the use of opioids. How can regional anesthesia, in your opinion, contribute to reducing the role of anesthesia and perioperative care in the opioid pandemic problem?

Anywhere we can reduce the use of opioids is a good thing, from many different standpoints. Regional anesthesia can help us avoid postoperative side effects, such as itching, nausea, dizziness, drowsiness, throwing up, and constipation.

A few years ago at one of the SRA meetings, Eugene Viscusi, who was either the president or about to become the president, stated that 6 to 8% of all United States patients undergoing surgery would develop opioid use disorder if they were prescribed opioids afterward. Anything that we can do to mitigate or reduce the number of opioids that people need going out the door is a good thing; for example, we can attenuate or ameliorate their pain for 24 hours, or even up to 72 hours or longer if we’re using catheters, and use other drugs that cause really long-lasting analgesia.

I think that we’re really doing patients a good service in three ways:

- Reducing side effects

- Reducing the higher doses or longer duration that increase the potential for opioid use disorder

- Then there’s the occasional patient with sleep-disordered breathing, who gets opioids and can have a crisis at home. I haven’t seen that very often, but it’s certainly well-documented in the literature.

Three different areas where regional anesthesia can offset opioids in ways that help patients.

- When you clicked send to submit your manuscript to the publisher, what was your dream outcome for the book and what did you want to accomplish with it?

My biggest hope was that it would affect people in a way that changed their lives. I think all people who write books want to change people’s thought processes and, in effect, change lives, and influence people.

The favorable feedback and reviews from people who have read the book have been very satisfying, and, in that way, I think it’s been a big success.

- So, can you tell us the title of your next book and what it’s about?

It’s called “The Six Line Race Runner”. It’s actually a memoir.

I spent a few years living in Spain as a boy when my father was stationed at the US Air Force Base over there. It was an interesting time, at the end of General Franco’s tenure, when Spain was undergoing change. It had been a much more backward country in the years after World War II, but, by the 1970s and 80s, Spain was just starting to turn the corner to become a more modern European country.

It was just a great time to be there and I experienced many really wonderful things. Even though we longed to go back home, we always knew how privileged and lucky we were to be there at that time.

I met a lot of great people and I did a lot of growing up there. So it’s a sort of “coming-of-age” book.

The “Six Line Race Runner” refers to a particular type of lizard. We had this little band of boys who used to love to catch lizards in the gulleys around our houses, and our most sought-after quarry was the “Six Line Race Runner”. It also held some symbolic importance, so the hunt for the lizard frames a memoir of that last year spent in Spain.