Pain remains one of the most common reasons patients seek medical care globally. As the complexity and diversity of pain presentations evolve—from acute musculoskeletal injuries to chronic inflammatory and neuropathic disorders—the need for targeted and well-tolerated pain management strategies has never been greater. While systemic analgesics, particularly oral medications, are widely used, their adverse effects and systemic absorption challenges limit their utility in certain patient populations.

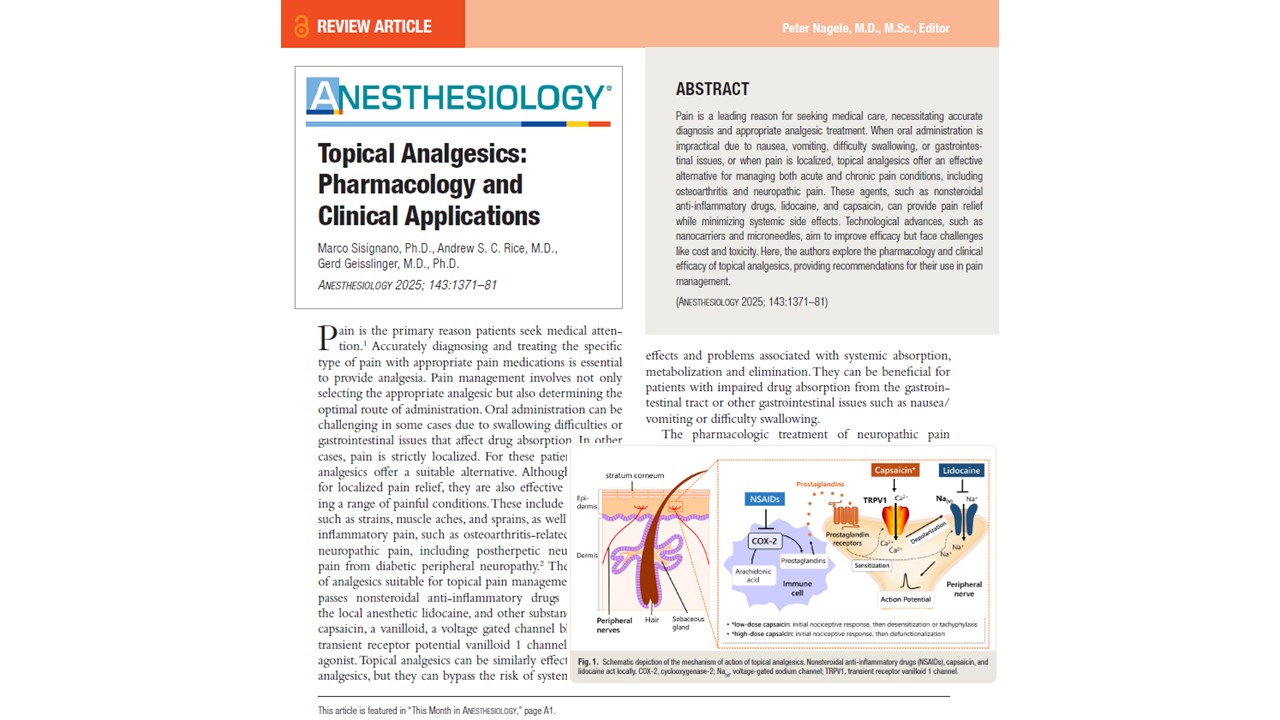

Topical analgesics represent a promising therapeutic alternative, as shown by Sisignano et al. 2025 in Anesthesiology. These agents deliver localized pain relief with minimal systemic involvement, offering significant benefits in conditions like osteoarthritis, diabetic peripheral neuropathy, and postherpetic neuralgia. Their ability to bypass gastrointestinal absorption and reduce systemic toxicity enhances their appeal, particularly in multimodal analgesia regimens.

In this article, we examine the pharmacological basis, clinical efficacy, delivery challenges, and future directions of topical analgesics, offering anesthesiologists and pain management specialists a comprehensive overview of this crucial domain in contemporary pain care.

Challenges of drug transport across the skin

The skin, the body’s largest organ, poses significant barriers to drug delivery, particularly through its outermost layer, the stratum corneum. Comprising multiple layers of cornified keratinocytes (corneocytes), this structure is both lipophilic and dense, restricting drug penetration.

Key absorption pathways:

- Intercellular route: Passage through the lipid–protein matrix.

- Intracellular route: Movement through corneocytes, hindered by the differing lipophilic and hydrophilic properties.

- Transappendageal route: Via sweat glands, sebaceous glands, and hair follicles.

To overcome these barriers, modern topical formulations often incorporate chemical permeation enhancers (e.g., ethanol, dimethyl sulfoxide), colloidal carriers (e.g., liposomes, nanoemulsions), and polymeric gels that increase solubility, optimize release kinetics, and minimize skin irritation.

Topical NSAIDs: mechanism and efficacy

Mechanism of action

Topical nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) work by inhibiting cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) enzymes, thereby reducing local prostaglandin production and peripheral sensitization. Common agents include:

- Diclofenac

- Ketoprofen

- Piroxicam

These formulations deliver effective concentrations to the inflamed tissues with significantly reduced plasma levels, minimizing gastrointestinal adverse effects typically associated with systemic NSAID use.

Clinical evidence

- Acute musculoskeletal pain: Diclofenac emulgel demonstrated a Number Needed to Treat (NNT) of 1.8, indicating high efficacy.

- Osteoarthritis: Topical diclofenac showed efficacy with an NNT of 5.0 for pain reduction over <6 weeks.

Topical NSAIDs have also been found to accumulate in synovial tissue, reaching concentrations 10–20 times higher than in synovial fluid or plasma, supporting their local activity.

Safety profile

Meta-analyses confirm the superior gastrointestinal safety of topical NSAIDs compared to oral formulations. Adverse effects are typically limited to mild local skin reactions.

Capsaicin: pharmacology and clinical implications

Capsaicin, the active compound in chili peppers, acts by binding to TRPV1 receptors on nociceptive neurons. Its pharmacologic effects are dose-dependent:

- Low-dose (<1%): Causes receptor desensitization (tachyphylaxis) and transient analgesia.

- High-dose (8%): Leads to defunctionalization of nerve endings via calcium overload and cytoskeletal degradation, providing prolonged relief.

Clinical efficacy

- Postherpetic neuralgia and diabetic neuropathy: The 8% capsaicin patch (Qutenza) is FDA-approved and offers moderate efficacy, although with an NNT of 10.6, its effectiveness is considered modest.

- Cancer pain (neuropathic component): Can be used as a co-analgesic.

- Low-dose capsaicin: Evidence for chronic pain relief is minimal.

Safety and limitations

High-dose capsaicin is associated with transient local reactions (burning, erythema). Importantly, nerve fiber regrowth occurs over a 24-week period, with no long-term sensory loss observed. Efficacy depends on the presence of TRPV1-positive nerve fibers, limiting its use in non-TRPV1-mediated pain.

Lidocaine: pharmacologic properties and clinical role

Mechanism of action

Lidocaine is a voltage-gated sodium channel (Nav 1.7/1.8) inhibitor, reducing peripheral nerve excitability and pain signal transmission. It is available in:

- Low-dose formulations: Include creams, gels, and ointments.

- High-dose patches (5%): Used for more persistent neuropathic pain.

Clinical use

- Postherpetic neuralgia: Main indication for the 5% patch.

- Osteoarthritis and diabetic neuropathy: Used as adjunct therapy.

- Carpal tunnel syndrome: May provide relief.

Despite good patient tolerability, recent meta-analyses rate the evidence for efficacy as low, relegating lidocaine patches to second-line treatment for neuropathic pain.

Pharmacokinetics

- Only 3 ± 2% of lidocaine from patches is systemically absorbed.

- It is rapidly metabolized in the liver and excreted via the kidneys.

Other topical analgesics: emerging options

Several less-established compounds are under investigation for topical pain relief:

Gabapentin

- Studied for vulvodynia.

- Limited evidence and small sample sizes prevent definitive recommendations.

Combination creams (baclofen, amitriptyline, ketamine)

- Aim to target multiple pain pathways.

- Clinical trials for chemotherapy-induced neuropathy found no superiority over placebo.

Ambroxol

- Traditionally, a mucolytic and ambroxol blocks Nav1.8 channels.

- Topical application shows potential in case studies but lacks high-quality evidence.

Botulinum toxin A

- Subcutaneous/intradermal use in refractory neuropathic pain.

- Third-line therapy with selective efficacy in patients with thermal sensitivity and evoked pain.

Technological innovations in topical delivery

Emerging technologies aim to enhance drug penetration while minimizing systemic exposure:

- Nanocarriers: Liposomes, nanoemulsions, solid lipid nanoparticles.

- Microneedle-assisted delivery: Facilitates deeper tissue penetration.

- Microemulsions: Early studies have shown promising results in pain reduction (e.g., diclofenac microemulsion reduced pain by≥50% in 9 of 11 patients).

Considerations:

- High production costs.

- Potential toxicity.

- There is a need for personalized approaches tailored to individual skin types and conditions.

Conclusion

Topical analgesics offer a vital alternative for pain management, especially in patients who cannot tolerate systemic therapies. Their localized action, reduced systemic absorption, and favorable safety profiles make them essential tools in the armamentarium of anesthesiologists and pain specialists.

Among the currently available agents:

- Topical NSAIDs (particularly diclofenac and ketoprofen) are highly effective for acute and inflammatory pain.

- High-dose capsaicin is modestly effective for neuropathic pain but is limited by its burning sensation and high NNT.

- Lidocaine patches remain valuable as second-line therapy with excellent tolerability but limited efficacy data.

Although several novel agents and formulations are under development, most lack robust evidence from large-scale randomized controlled trials. Future research must focus on optimizing delivery systems, establishing standardized protocols, and identifying biomarkers to tailor topical analgesics to individual patient needs. In the realm of regional anesthesia and multimodal pain management, the role of topical agents is poised to expand, particularly with technological advances that promise to improve efficacy without compromising safety. For anesthesiologists and pain specialists committed to personalized, evidence-based care, topical analgesics represent both a powerful present solution and a promising future frontier.

For more information, refer to the full article in Anesthesiology.

Sisignano M, Rice ASC, Geisslinger G. Topical Analgesics: Pharmacology and Clinical Applications. Anesthesiology. 2025 Nov 1;143(5):1371-1381.

Learn more about pain management strategies in our Anesthesiology Module on NYSORA 360—an essential learning resource for residents with up-to-date, practical guidance across perioperative care.