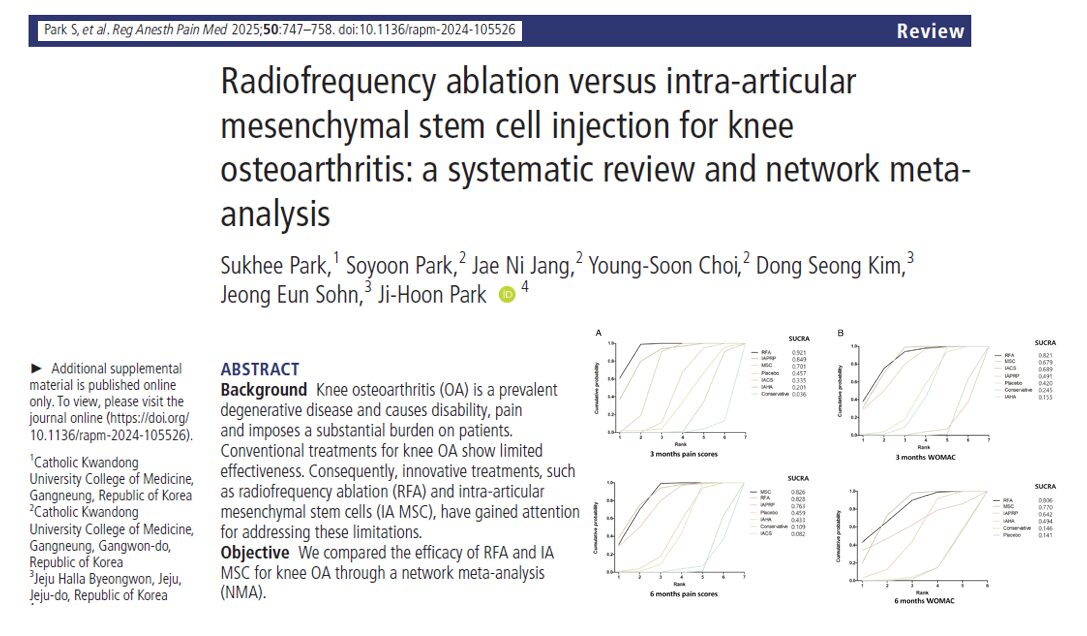

Radiofrequency ablation (RFA) of the genicular nerves has emerged over the past 15 years as a valuable interventional treatment for chronic knee pain, particularly in patients with osteoarthritis (OA). This minimally invasive procedure targets articular sensory nerve branches around the knee joint, offering significant, and in many cases prolonged, pain relief.

Despite the initial success reported in early randomized controlled trials (RCTs), ongoing studies have produced conflicting data, igniting debate within the pain medicine community. A recent discourse published in Regional Anesthesia & Pain Medicine by Ferreira-Silva et al. systematically dissects these controversies and proposes strategies for personalized and anatomically guided interventions.

Background: understanding RFA in knee OA

Chronic knee pain, especially from OA, is a leading cause of disability worldwide. While physical therapy, NSAIDs, and intra-articular corticosteroid injections are standard treatments, their long-term efficacy is often limited. Repeated injections can even accelerate joint degeneration and reduce bone mineral density.

RFA offers a more targeted approach by thermally disrupting the small genicular nerves that transmit pain signals from the knee capsule. Depending on the technique and patient selection, this can yield significant pain relief for 6 to 12 months or longer.

Core controversies and evolving practices in genicular nerve RFA

-

Prognostic blocks before RFA: essential or excessive?

Prognostic blocks involve injecting a local anesthetic near the genicular nerves to predict the success of subsequent RFA.

Arguments in favor:

- Help identify patients who will most benefit from RFA.

- Improve clinical efficacy and cost-effectiveness.

- Reduce unnecessary procedures and complications.

Arguments against:

- OA pain is typically well-localized, reducing the diagnostic utility.

- High false-positive rates due to anesthetic spread.

- Some studies show no difference in outcome with or without blocks.

When to use:

- Post-arthroplasty pain.

- Atypical presentations (neuropathic features, significant synovitis).

- Patients with psychological comorbidities.

Takeaway: Prognostic blocks should be personalized, and more high-quality trials are needed to refine their role.

-

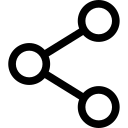

Where to place the cannula: classical vs revised targets

The original Choi et al. protocol defined targets at the diaphysis-epiphysis junction of the femur and tibia. However, new anatomical studies suggest that a more distal and posterior placement might capture a broader set of nerve branches, particularly the deep and superficial branches of the superomedial and superolateral genicular nerves.

Why this matters:

- Classic targets may miss key branches.

- Revised sites better align with current anatomical mapping.

Recommended technique:

- Bipolar RFA with two lesions per nerve (mid and posterior femur) to maximize coverage.

- Targeting both classical and revised landmarks improves outcomes.

-

Targeting more than three nerves: toward customized protocols

Historically, RFA focused on three nerves:

- Superior medial genicular nerve (SMGN)

- Superior lateral genicular nerve (SLGN)

- Inferior medial genicular nerve (IMGN)

New evidence suggests this is insufficient, given that the anterior knee capsule receives innervation from up to 10 articular branches.

Additional targets may include:

- Medial/lateral branches of the nerve to vastus intermedius (NVI)

- Nerve to vastus lateralis (NVL)

- Nerve to vastus medialis (NVM)

- Infrapatellar branch of the saphenous nerve (IPBSN)

- Recurrent fibular nerve (RFN)

Recommended expansions:

- For medial + patellofemoral OA: 5-nerve protocol (add NVI branches)

- For lateral compartment OA: consider RFN

- For anterior patellar pain: target NVL and NVM

Caution: Avoid full denervation to prevent Charcot arthropathy. Use targeted expansion based on imaging and pain mapping.

-

Ultrasound vs fluoroscopy: which guidance technique is superior?

Fluoroscopy:

- Most widely used (85% of practitioners).

- Precise for bony landmarks.

- Better in obese patients or post-TKA.

Ultrasound (US):

- Superior for soft-tissue landmarks (NVM, NVL).

- Visualizes vessels—important in vascular-rich knees.

- Office-based and more cost-effective.

Best approach:

- US is preferred for soft-tissue nerve targets (NVL, IPBSN).

- Fluoroscopy is better for deep periosteal lesions.

- A combined technique may offer superior precision but needs research validation.

-

Pulsed radiofrequency (pRF): a role in genicular nerve treatment?

pRF vs RFA:

- pRF modulates nerve function without destroying it.

- Reduced risk of neuritis and neuroma.

- Less effective for deep intra-articular pain sources.

Where pRF might help:

- Treating neuropathic pain (e.g., saphenous or infrapatellar neuralgia).

- High-risk patients where ablation may cause complications.

Current consensus: Use RFA for primary OA pain. Consider pRF only for superficial nerve conditions or as a second-line tool.

-

Post-TKA pain: Can RFA help?

Up to 20% of total knee arthroplasty (TKA) patients experience persistent pain. The causes are complex and not always addressed by RFA.

Challenges:

- Pain may stem from inflammation, neuropathy, or central sensitization.

- Subchondral nerves may persist even after joint resurfacing.

Evidence:

- Mixed results in RCTs.

- Best outcomes when patients respond positively to prognostic blocks.

Advice:

- Carefully rule out mechanical causes (malalignment, infection).

- Use RFA only in selected patients with intra-articular pain confirmed by nerve block.

Step-by-step guide: optimal RFA protocol

- Diagnose: Confirm OA with imaging and clinical exam.

- Evaluate: Consider a prognostic block for uncertain cases.

- Plan targets: Use anatomical mapping to decide on 3, 5, or expanded nerve set.

- Choose guidance: Fluoroscopy for bony targets, US for soft-tissue nerves.

- Apply RFA: Perform bipolar lesions at multiple levels if needed.

- Monitor: Assess for pain relief and functional improvements post-procedure.

Final thoughts

As the field of pain medicine evolves, genicular nerve RFA stands out as a transformative tool for managing chronic knee pain. However, a one-size-fits-all approach no longer suffices. By embracing anatomical precision, evidence-based expansion of nerve targets, and tailored procedural strategies, clinicians can deliver better outcomes for their patients.

Further research, especially high-quality, comparative RCTs, will be crucial to solidify best practices. Until then, personalization, combined guidance techniques, and careful patient selection remain the cornerstones of successful genicular RFA.

For more detailed information, refer to the full article in RAPM.

For a detailed practical guide on ultrasound-guided genicular nerve ablation and many other interventional pain procedures, read our latest release, NYSORA’s Ultrasound-guided Interventional Pain Procedure Manual