FACTS

- Indications: elbow, forearm, and hand surgery

- Transducer position: short axis to arm, just distal to the pectoralis major insertion

- Goal: local anesthetic spread around axillary artery

- Local anesthetic: 15–20 mL

GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS

The axillary brachial plexus block is relatively simple to perform and may be associated with a lower risk of complications compared with interscalene (eg, spinal cord or vertebral artery puncture) and supraclavicular brachial plexus blocks (eg, pneumothorax). In clinical scenarios in which access to the upper parts of the brachial plexus is difficult or impossible (eg, local infection, burns, indwelling venous catheters), the ability to anesthetize the plexus at a more distal level may be important. Although individual nerves can usually be identified this is not absolutely necessary because the deposition of local anesthetic around the axillary artery is sufficient for an effective block.

ULTRASOUND ANATOMY

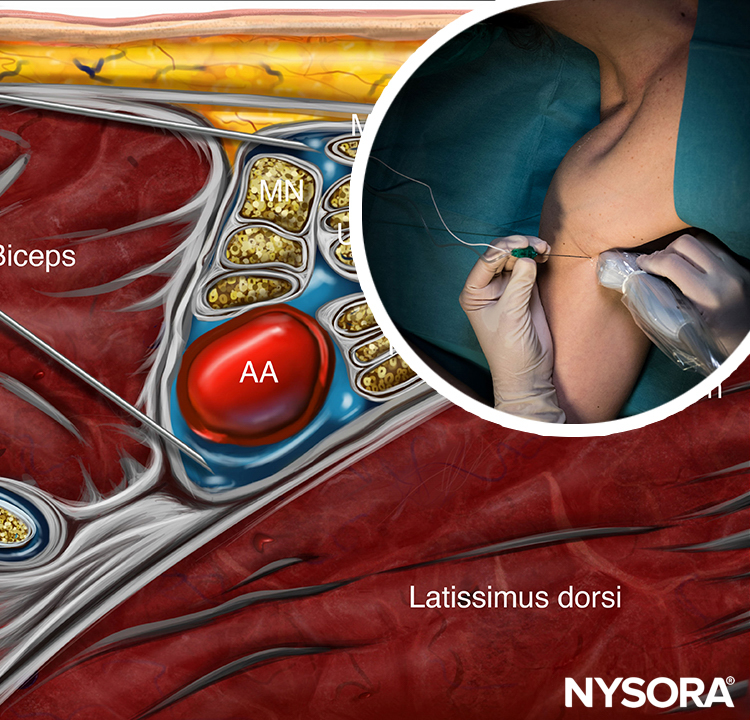

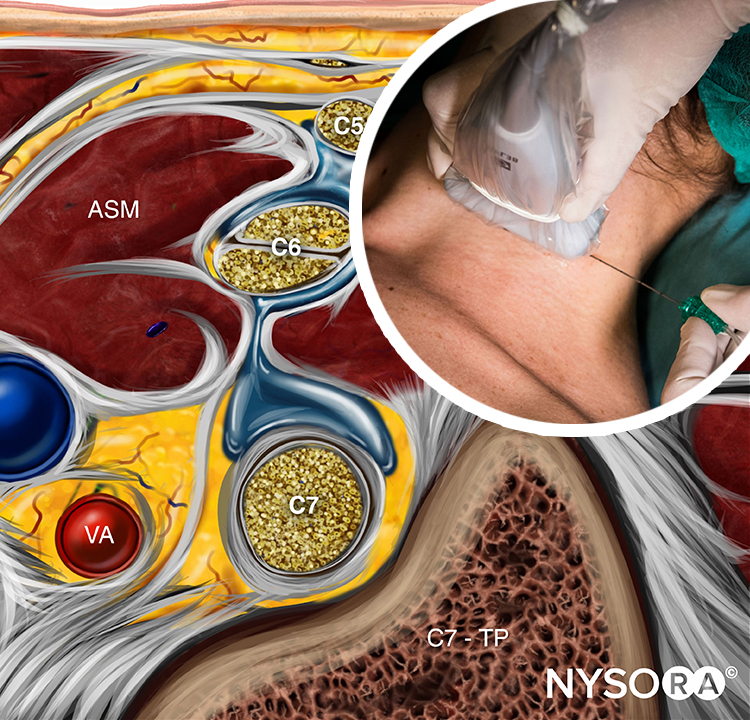

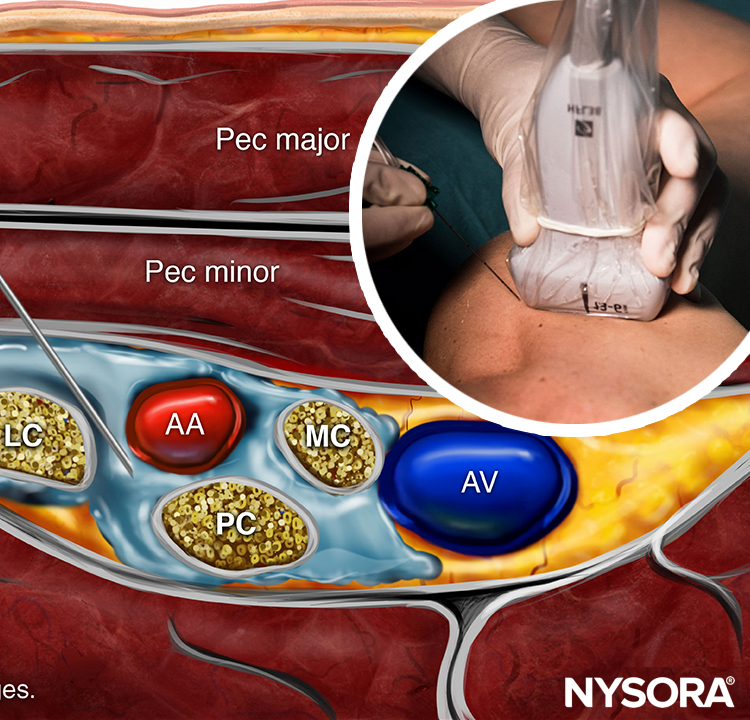

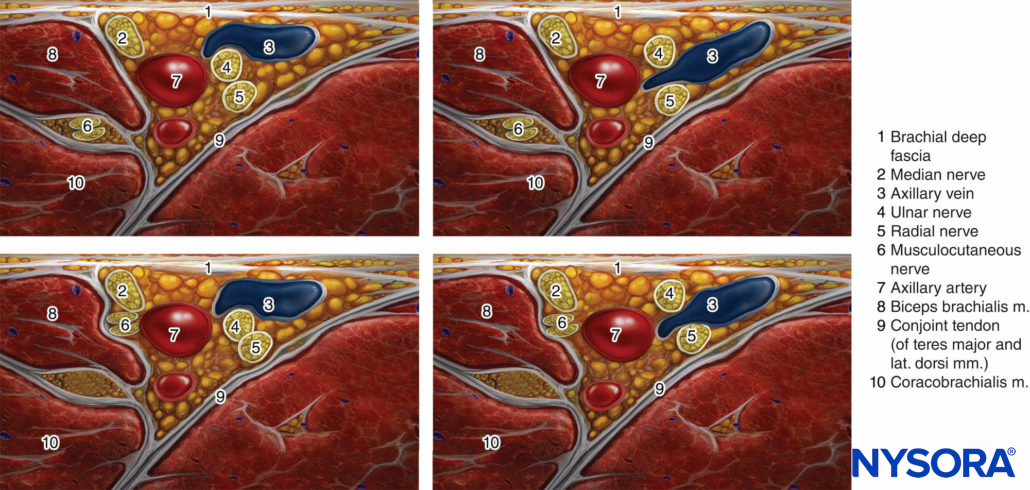

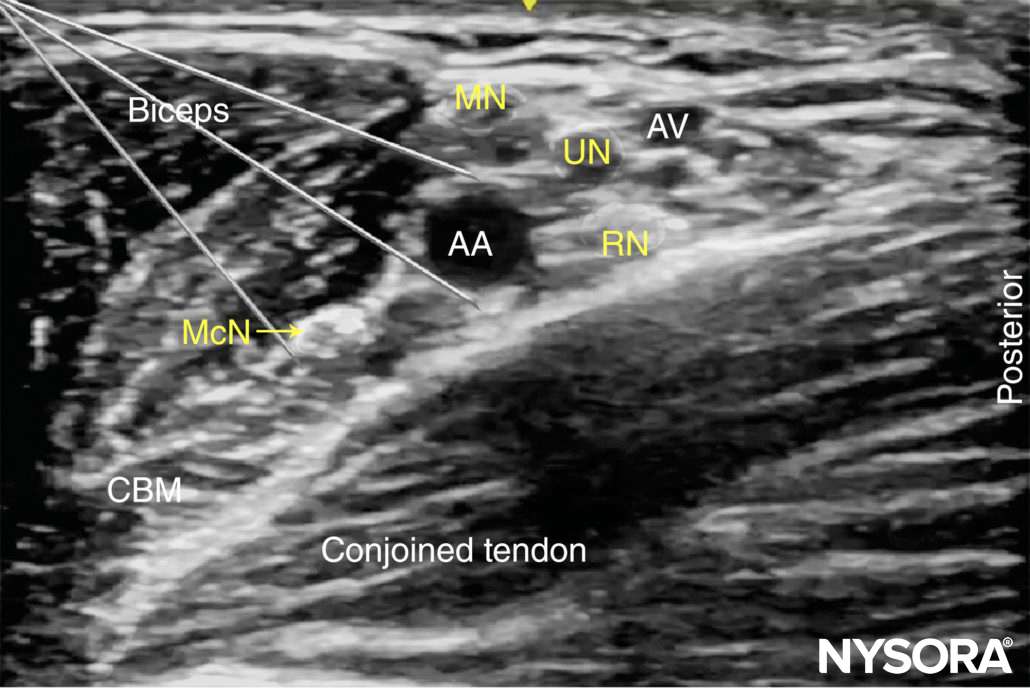

The structures of interest are superficial (1–3 cm below the skin), and the axillary artery is readily identified within a centimeter of the skin surface on the medial aspect of the proximal arm (Figure 1-A). The artery is accompanied by one or more axillary veins, often located medially to the artery. Importantly, excessive pressure with the transducer during imaging may compress the veins, rendering veins invisible and prone to puncture with the needle. Surrounding the axillary artery, three of the four principal branches of the brachial plexus can be seen: the median (superficial and lateral to the artery), the ulnar (superficial and medial to the artery), and the radial (posterior and lateral or medial to the artery) nerves. The nerves appear as round hyperechoic structures (Figure 1-B). Several authors have reported the anatomical variations of the nerves relative to the axillary artery; Figure 2 illustrates the most common patterns.

Three muscles surround the neurovascular bundle: the biceps (anterior and superficial), the wedge-shaped coracobrachialis (anterior and deep), and the conjoined tendon of the teres major and latissimus dorsi (medial and posterior). The musculocutaneous nerve is located in the fascial layers between the biceps and coracobrachialis muscles, though its location is variable and can be seen within either muscle. It is usually seen as a hypoechoic flattened oval structure with a bright hyperechoic rim. Moving the transducer proximally and distally along the long axis of the arm, the musculocutaneous nerve appears to move toward or away from the neurovascular bundle in the fascial plane between the two muscles. Variations are determined by the position of the musculocutaneous nerve relative to the median nerve and by the position of the ulnar nerve relative to the axillary vein. For additional information see Functional Regional Anesthesia Anatomy.

FIGURE 1. (A) Cross-sectional anatomy of the axillary fossa and ultrasound image (B) of the terminal nerves of brachial plexus. The BP is seen scattered around the axillary artery and enclosed within the adipose tissue compartment containing the axillary artery (AA), and axillary veins (AV). MCN, musculocutaneous nerve. MN, median nerve; RN, radial nerve; UN, ulnar nerve; MACN, medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve; CBM, coracobrachialis muscle.

FIGURE 2. Most common patterns of nerve location around the axillary artery in ultrasound-guided axillary brachial plexus block.

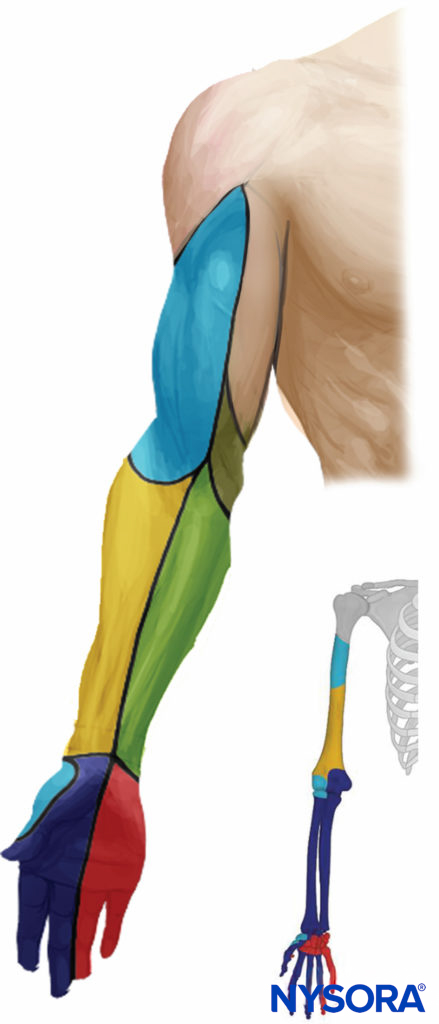

DISTRIBUTION OF ANESTHESIA

The axillary brachial plexus block (including the musculocutaneous nerve) results in anesthesia of the upper limb from the mid-arm down to and including the hand. Importantly, the block lends its name from the approach and not from the axillary nerve, which itself is not blocked because it departs from the posterior cord more proximally in the axilla. Therefore, the skin over the deltoid muscle is not anesthetized (Figure 3). With nerve stimulator and landmark-based techniques, the block of the musculocutaneous nerve is often unreliable. However, the musculocutaneous nerve is readily visualized and reliably anesthetized by a separate injection using ultrasound guidance. When required, the medial skin of the upper arm (intercostobrachial nerve, T2) can be blocked by an additional subcutaneous injection just distal to the axilla.

FIGURE 3. Sensory distribution after axillary brachial plexus block.

EQUIPMENT

- Ultrasound machine with linear transducer (8–14 MHz), sterile sleeve, and gel

- Standard nerve block tray

- Syringes with local anesthetic (20 mL)

- 5-cm, 22-gauge, short-bevel, insulated stimulating needle

- Peripheral nerve stimulator

- Opening injection pressure monitoring system

- Sterile gloves

Learn more about Equipment for Peripheral Nerve Blocks

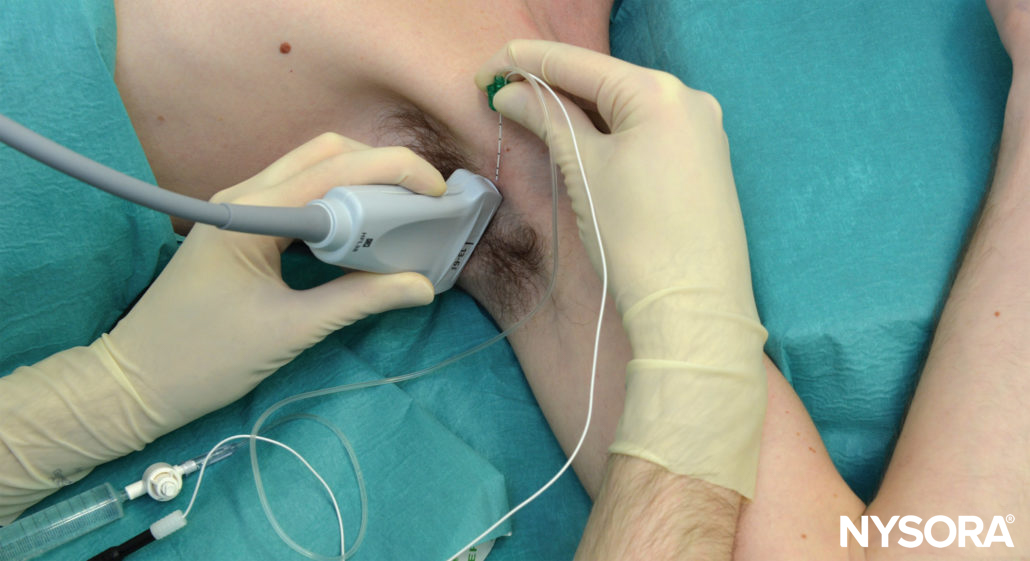

LANDMARKS AND PATIENT POSITIONING

An abduction of the arm to 90 degrees is necessary to allow for transducer placement and needle advancement, (Figure 4). Care should be taken not to over-abduct the arm, as this may cause patient discomfort as well as traction on the brachial plexus, making it theoretically more vulnerable to injury by needle or injection. The pectoralis major muscle is palpated as it inserts onto the humerus, and the transducer is placed on the skin immediately distal to that point, perpendicular to the axis of the arm. The starting point should have the transducer overlying both the biceps and triceps muscles (ie, on the medial aspect of the arm). Sliding the transducer proximally will bring the axillary artery, the conjoint tendon and the terminal branches of the brachial plexus into view, if not readily apparent.

FIGURE 4. Patient position and needle insertion for ultrasound-guided (in-plane) axillary brachial plexus block. All needle redirections are done through the same needle insertion site.

GOAL

The goal is to deposit local anesthetic around the axillary artery. Typically, two or three injections are required. In addition, an aliquot of local anesthetic should be injected around the musculocutaneous nerve.

From the Regional Anesthesia Manual: Reverse Ultrasound Anatomy for an axillary brachial plexus block with needle insertion in-plane and local anesthetic spread (blue). The figure shows 3 needle injections. AA, axillary artery; AV, axillary vein; McN, musculocutaneous nerve; MN, median nerve; UN, ulnar nerve; RN, radial nerve; MbCN, medial brachial cutaneous nerve.

TECHNIQUE

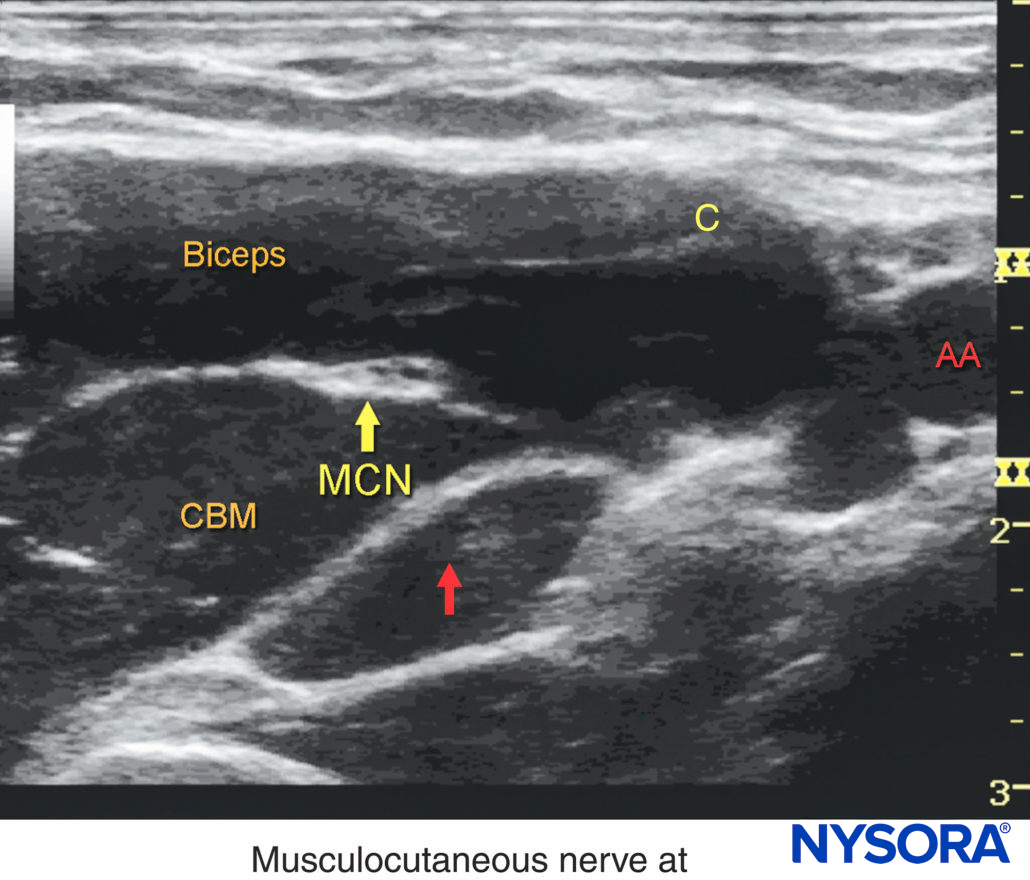

The skin is disinfected and the transducer is positioned in the short axis orientation to identify the axillary artery about 1–3 cm from the skin surface. Once the artery is identified, an attempt is made to identify the hyperechoic median, ulnar, and radial nerves (Figure 5). However, these may not always be well visualized with ultrasound. Frequently present, an acoustic enhancement artifact deep to the artery is often misinterpreted as the radial nerve. Prescanning should also reveal the position of the musculocutaneous nerve, in the plane between the coracobrachialis and biceps muscles or within either of the muscles (a slight proximal-distal movement of the transducer is often required to bring this nerve into view) (Figure 6).

FIGURE 5. The median (MN), ulnar (UN), and radial (RN) nerves are seen scattered around the axillary artery (AA). The musculocutaneous nerve (MCN) is seen between the biceps and coracobrachialis muscle (CBM), away from the rest of the brachial plexus. AV, axillary vein.

FIGURE 6. The musculocutaneous nerve (MCN) is located few cms away from the axillary artery (AA) between the biceps and the coracobrachialis muscle. The course of the MCN along the upper arm display frequent anatomic variations. Systematic scanning to identify the nerve and a separate injection of local anesthetic are usually required for a successful axillary brachial plexus block.

The needle is inserted in-plane from the anterior aspect and directed toward the posterior aspect of the axillary artery (Figure 7). Because nerves and vessels are positioned closely together in the neurovascular bundle by adjacent musculature, advancement of the needle may require careful hydrodissection with a small amount of local anesthetic or other injectates. This technique involves the injection of 0.5–2 mL, indicating the plane in which the needle tip is located. The needle is then carefully advanced stepwise few millimeters at a time. The use of nerve stimulation is recommended to decrease the risk of needle-nerve injury during needle advancement. Local anesthetic should be deposited posterior to the artery first, to avoid displacing the structures of interest deeper and obscuring the nerves, which may occur if injections for the median or ulnar nerves are carried out first.

FIGURE 7. Needle insertions for axillary brachial plexus block. Axillary block can be accomplished by two to four separate injections, depending on the disposition of the nerves around the axillary artery (AA) and the quality of the image. MCN, musculocutaneous nerve; MN, median nerve; RN, radial nerve; UN, ulnar nerve. AA, axilary vein, AV, axillary vein.

The posteriorly located radial nerve is often visualized more clearly once surrounded by local anesthetic. Once 5–7 mL has been administered, the needle is withdrawn almost to the level of the skin, redirected toward the median and ulnar nerves, and a further 7–10 mL is injected in these areas to complete the spread around the nerves. The described sequence of injection is demonstrated in Figure 8.

FIGURE 8. This image demonstrates the ideal distribution pattern of local anesthetic. In this particular disposition of nerves, a single needle pass superficially to the artery allows for two injections: one for the median (MN) and a second one between the ulnar (UN) and radial (RN). The musculocutaneous (MCN) requires a separate injection.

An alternative, perivascular approach is to simply inject local anesthetic deep to the artery, at the 6 o’clock position, instead of targeting the three nerves individually. This technique may shorten the duration of the block procedure, but also delay onset time, resulting in no difference in total time from skin puncture to the onset of the surgical block. The last step in the procedure, the needle is withdrawn and redirected toward the musculocutaneous nerve. Once adjacent to the nerve (stimulation will result in elbow flexion), 5–7 mL of local anesthetic is deposited. Occasionally, the musculocutaneous nerve will lie in close proximity to the median nerve, rendering a separate injection unnecessary. In an adult patient, 20 mL of local anesthetic is usually adequate for successful block, although successful blocks have been described with smaller volumes. Adequate spread within the axillary brachial plexus sheath is necessary for success but infrequently seen with a single injection. This is accomplished with two to three redirections and injections of 5-7 mL are usually necessary for a reliable block, as well as a separate injection to block the musculocutaneous nerve.

TIPS

- Frequent aspiration and slow administration of local anesthetic are critical for decreasing the risk of intravascular injection. Cases of systemic toxicity have been reported after apparently straightforward ultrasound-guided axillary brachial plexus blocks.

- If no spread is seen on the ultrasound image despite local anesthetic injection, the tip of the needle may be located in a vein. If this occurs, injection should be halted immediately and the needle is withdrawn slightly. Pressure on the transducer should be eased before reassessing the ultrasound image for the presence of vascular structures.

- Anatomic variations in the position of the musculocutaneous nerve have been described. In 16% of cases, the musculocutaneous nerve splits off of the median nerve distally to the axilla. In this case, a separate injection is not needed to block the musculocutaneous nerve as it will be blocked by the local anesthetic injected around the median nerve.

CONTINUOUS ULTRASOUND-GUIDED AXILLARY BLOCK

The indwelling axillary catheter is a useful technique for analgesia and sympathetic block. The goal of the continuous axillary block is to place the catheter within the vicinity of the branches of the brachial plexus (ie, within the “sheath” of the brachial plexus). The procedure is similar to that previously described in Ultrasound-Guided Interscalene Brachial Plexus. The needle is typically inserted in-plane from the anterior to posterior direction, just as in the single-injection technique). After an initial injection of local anesthetic to confirm proper needle tip position posterior to the axillary artery, the catheter is inserted 3–5 cm beyond the needle tip. Injection is then repeated through the catheter to document adequate spread of local anesthetic, wrapping the axillary artery. Alternatively, the axillary artery can be visualized in the longitudinal view with the catheter being inserted in the longitudinal plane alongside the axillary artery. The longitudinal approach requires a significantly greater degree of ultrasonographic skill; no data suggesting that one approach is more effective than the other currently exist.

Continue reading: Axillary Brachial Plexus Block – Landmarks and Nerve Stimulator Technique

Supplementary video related to this block can be found at Ultrasound-Guided Axillary Brachial Plexus Block Video

Clinical updates

Nijs et al. (Journal of Clinical Medicine, 2024) report in a systematic review and meta-analysis of 28 RCTs (n≈6,100) that ultrasound-guided axillary brachial plexus block achieves similar rates of adequate surgical anesthesia at 30 minutes compared with supraclavicular block, but a slightly lower success rate than infraclavicular block, with no differences in conversion to general anesthesia or need for supplemental analgesia. Infraclavicular blocks were performed more quickly, whereas onset times were comparable across approaches. Importantly, the axillary brachial plexus block showed a more favorable safety profile, with significantly less Horner’s syndrome and avoidance of pneumothorax or phrenic nerve involvement, supporting the axillary brachial plexus block as a preferred option in patients at higher risk from proximal block–related complications.

- Read more about the study HERE.

Grape et al. (European Journal of Anaesthesiology, 2021) report in a single-blinded randomized trial of 50 patients that an ultrasound-guided single-injection axillary brachial plexus block performed with extreme arm abduction significantly reduces procedure time (≈4 vs 6 min) compared with a multiple-injection technique, while achieving a similar block success rate at 30 minutes. The trade-off was a longer onset time with the single-injection approach, although all failures were readily resolved with supplemental blocks. These findings suggest that a single-injection technique may improve efficiency and reduce needle passes, at the cost of slower onset, and merit further study with block success as a primary outcome.

- Read more about the study HERE.